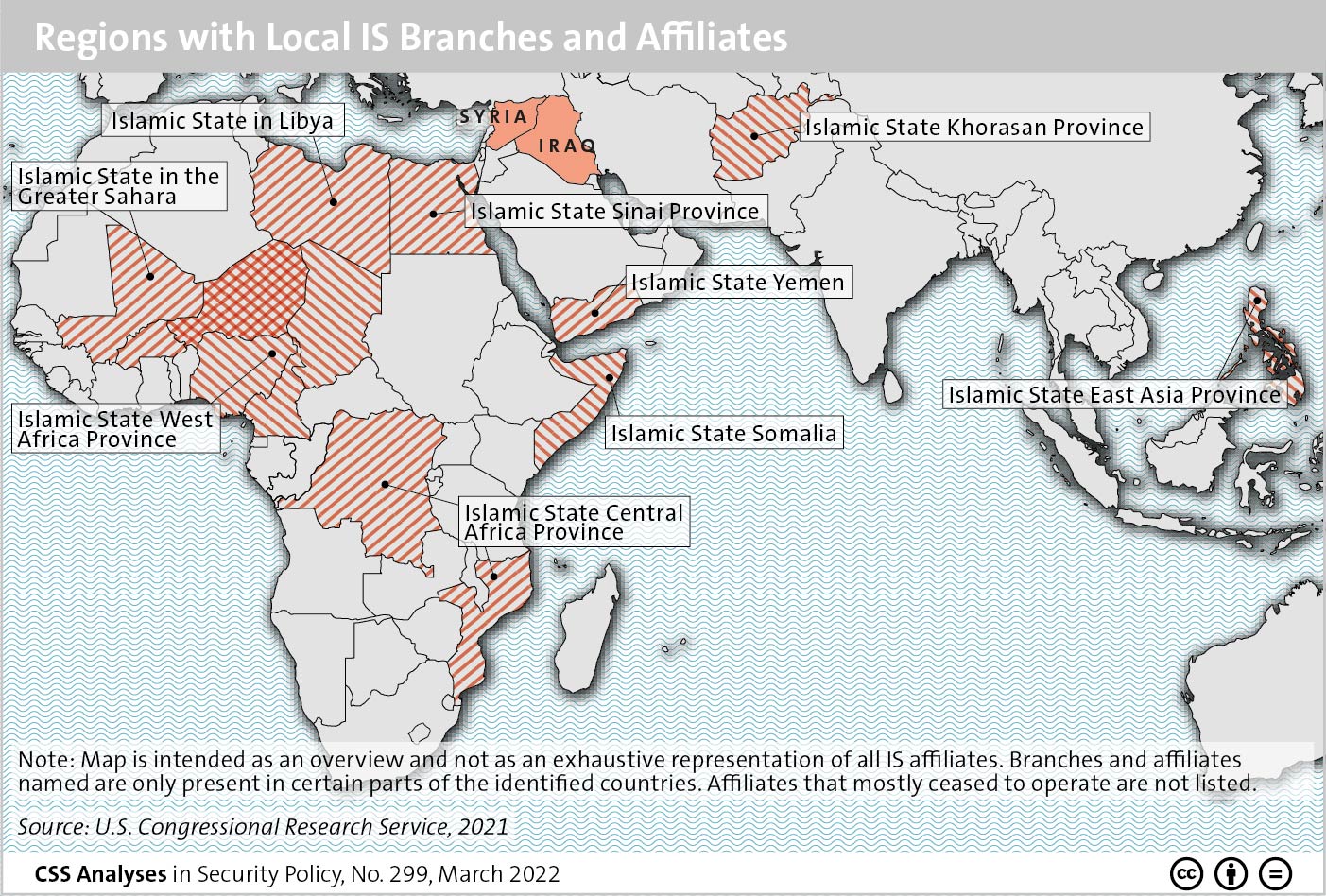

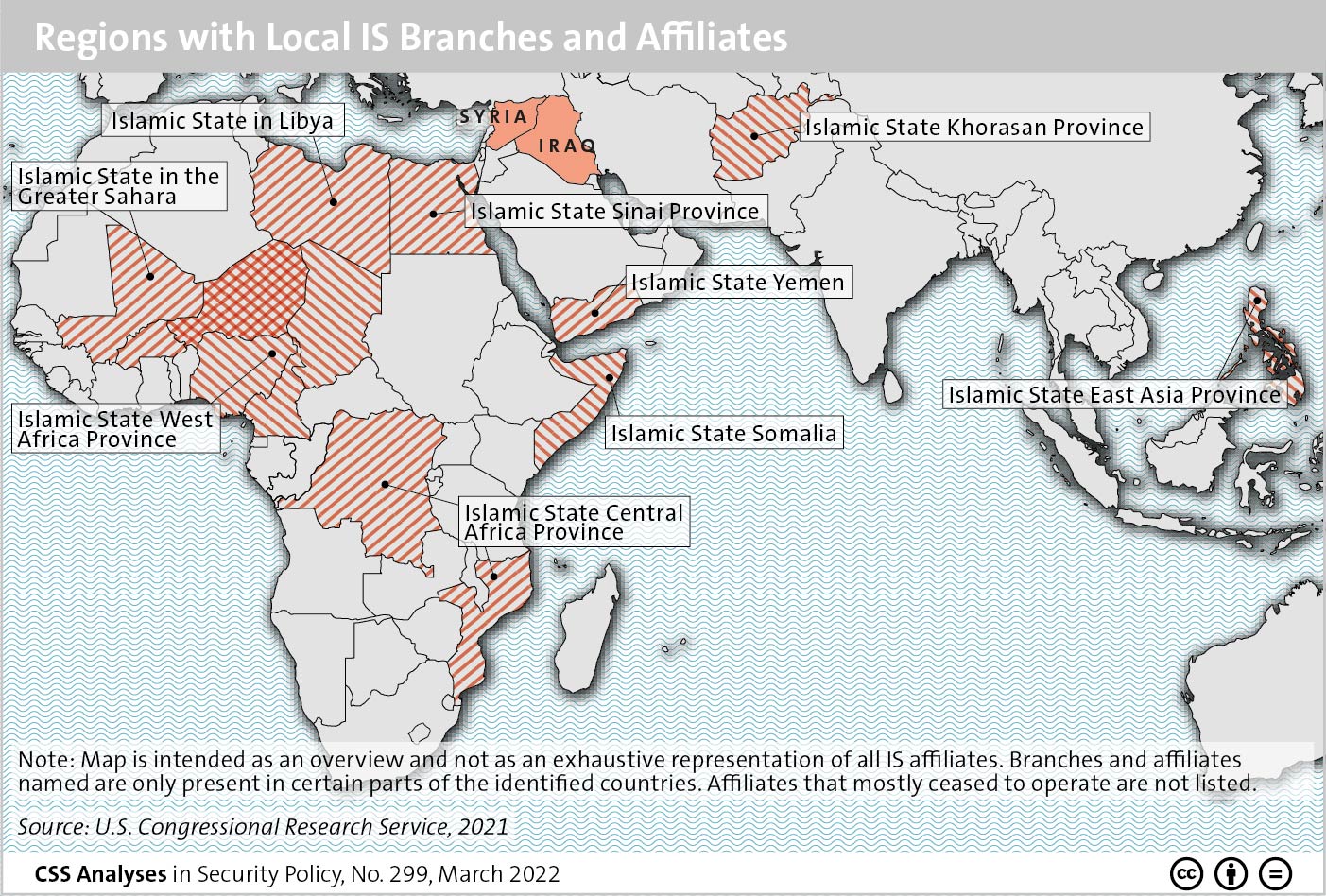

This week’s featured graphic shows the core IS’ state as of March 2022 as well as its affiliates in Africa, the Middle East and Asia. For a deeper assessment of the danger the IS still poses, read Fabien Merz’ CSS Analysis in Security Policy here.

This week’s featured graphic shows the core IS’ state as of March 2022 as well as its affiliates in Africa, the Middle East and Asia. For a deeper assessment of the danger the IS still poses, read Fabien Merz’ CSS Analysis in Security Policy here.

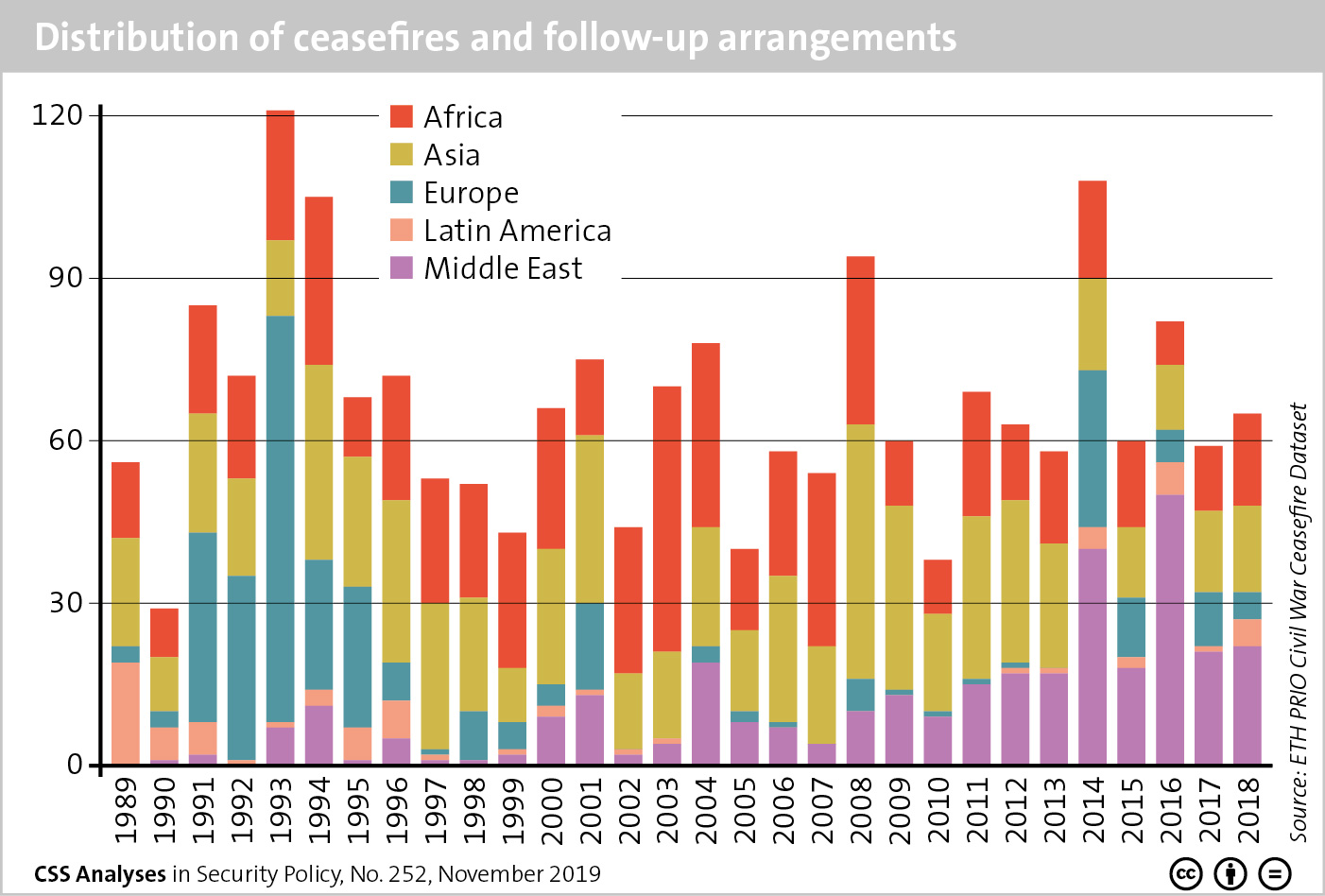

This week’s featured graphic shows the distribution of ceasefires and follow-up arrangements across Africa, Asia, Europe, Latin America and the Middle East between 1989 and 2018. For more on the role of ceasefires in intra-state peace processes, read Govinda Clayton, Simon J. A. Mason, Valerie Sticher and Claudia Wiehler’s CSS Analyses in Security Policy here.

This article was originally published by the Harvard International Review (HIR) on 17 April 2017.

President Donald Trump has made no secret of his skepticism toward America’s most important security pacts and military commitments, sending shockwaves throughout East Asia in April when he suggested that Japan, among others, should pay more for American protection and arm themselves with nuclear weapons to deter North Korea. The Japanese government relies heavily upon its mutual defense treaty with the United States for its national security, as Article IX of the Japanese Constitution strictly limits the nation’s war-making capacity. Trump’s electoral victory in November thus has startling implications for the island nation, prompting some question as to whether Japan should start pursuing a more conventional military arrangement for its own self-defense. However, the prospect of a rapidly aging population and a dwindling labor force will serve as an obstacle to future military self-sufficiency.

The Imperative for an Expanded Military

Following Japan’s defeat in the Second World War, US-led occupation forces drafted a new constitution in which the nation relinquished its right to wage war. The United States subsequently signed a security treaty with Japan, permitting the United States to maintain permanent military bases on Japanese soil “to deter armed attack” against a pacified, and thus vulnerable, Japan. US authorities also encouraged Japan to maintain a limited self-defense force to guard against growing Communist elements in China and Korea. However, the Self-Defense Forces (SDF), now composed of roughly 247,000 active personnel, engage primarily in international peacekeeping and disaster relief.

This article was originally published by the Pacific Forum CSIS on 9 November 2016.

Like most American Asia-watchers, I have no clue what the basic tenants of the incoming Trump administration’s Asia policy will be. I have learned from experience to discount at least half of what is said during presidential campaigns: Reagan was going to recognize Taiwan; Carter was going to withdraw US troops from the Korean Peninsula; etc., etc. The challenge is knowing which half not to believe.

While I don’t know what Trump’s Asia policy will be, I have a pretty good idea what it SHOULD be, so allow me to offer some unsolicited advice.

The pivot is dead, long live the pivot. The “pivot” or “rebalance” toward Asia is an Obama slogan which will leave with him – it likely would have even if Clinton was elected – but America’s focus on Asia as a national security priority has been a bipartisan constant since the end of the Cold War and the centrality of the US alliance system in Asia (with Australia, Japan, Korea, the Philippines, and Thailand) – as in Europe (NATO) – has likewise been a bipartisan constant since the 1950s. The going in assumption seems to be that a Trump administration is less committed to maintaining the alliance system as a vital component of America’s security (as well as the security of our allies). If he truly believes this, he needs to say so and address the alternatives and consequences. What he SHOULD do is to reaffirm the centrality of both Asia and the US alliance system to America’s continuing commitment to sustaining peace and security in Asia and beyond. George H.W. Bush and Bill Clinton did this by producing overarching East Asia Strategy Reports; a new one is sorely needed.

This article was originally published by the Middle East Institute (MEI) on 16 June 2016.

What is Disaster Diplomacy?

Disaster diplomacy investigates how and why disaster-related activities (pre-disaster and post-disaster) influence conflict and cooperation. [1]

Planning, preparation, and damage reduction are part of pre-disaster activities, which are termed ‘disaster risk reduction,’ focusing on addressing the root causes of disasters. Those root causes are, fundamentally, power and politics (particularly as related to resource allocation), societal sectors gaining from others’ vulnerability, and preference for short-term profit over long-term safety. Post-disaster activities refer to response, reconstruction, and recovery.

There have been numerous case studies of disaster diplomacy, covering various countries, regions and time periods, as well as a wide array of hazards—from environmental phenomena, such as earthquakes and floods, to technology-related incidences, such as train crashes and poisonings. The case studies have investigated many types of diplomacy: bilateralism, multilateralism, intergovernmental and international organizations, nongovernmental entities, and international relations conducted by non-sovereign jurisdictions such as provinces or cities (often called para-diplomacy, proto-diplomacy, and micro-diplomacy). The case studies also encompass many forms of conflict, ranging from interstate war and internal insurrections to the absence of diplomatic relations, frosty interactions, and political disagreements.

Across all case studies, no examples have been found where disaster-related activities have created new diplomatic initiatives. To be sure, disaster-related activities can serve as a catalyst for pre-existing diplomatic endeavors. In such instances, cultural links, informal or secret diplomatic negotiations, interactions in multilateral organizations, trade connections, or business and economic development can provide the conditions conducive to spurring disaster diplomacy.