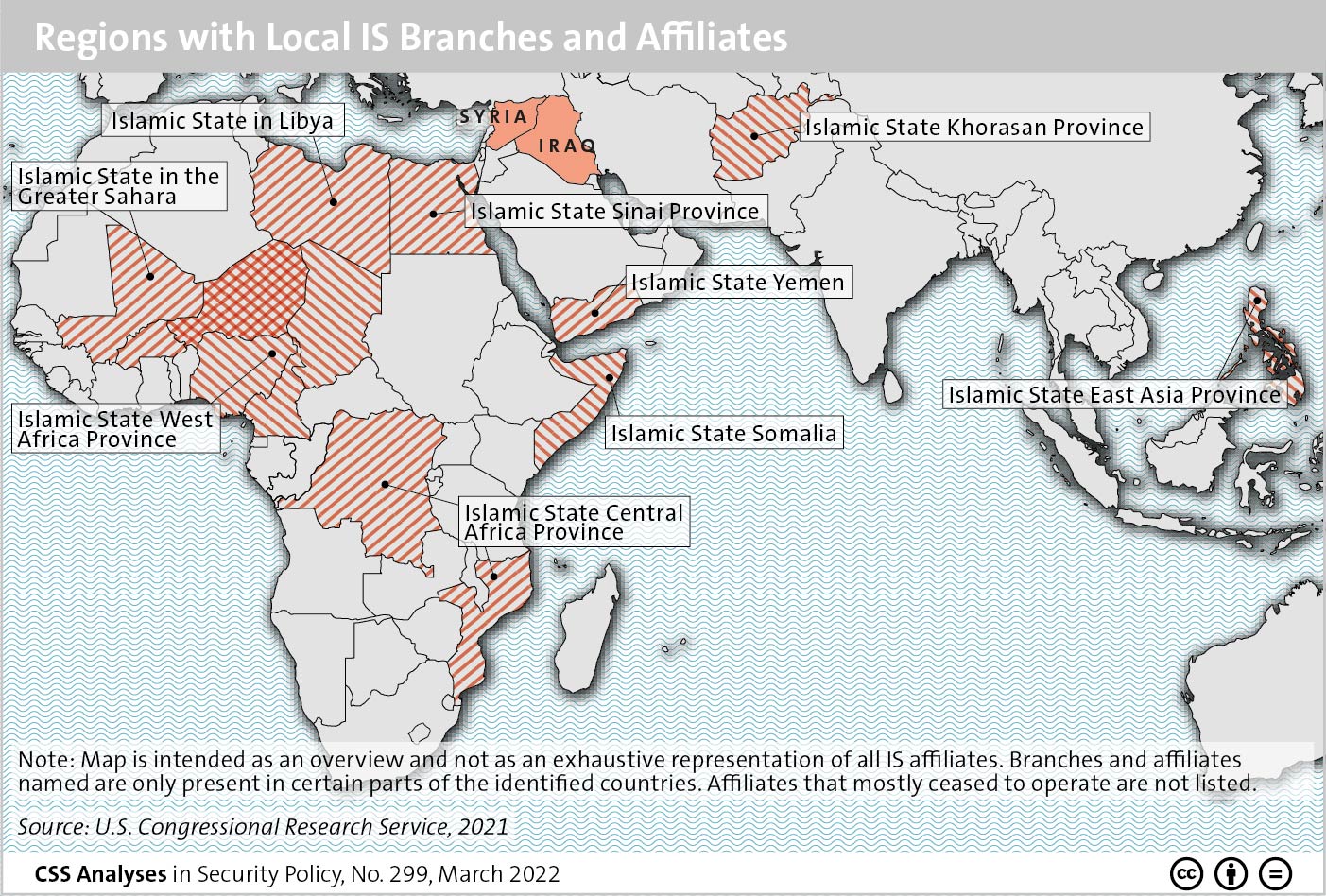

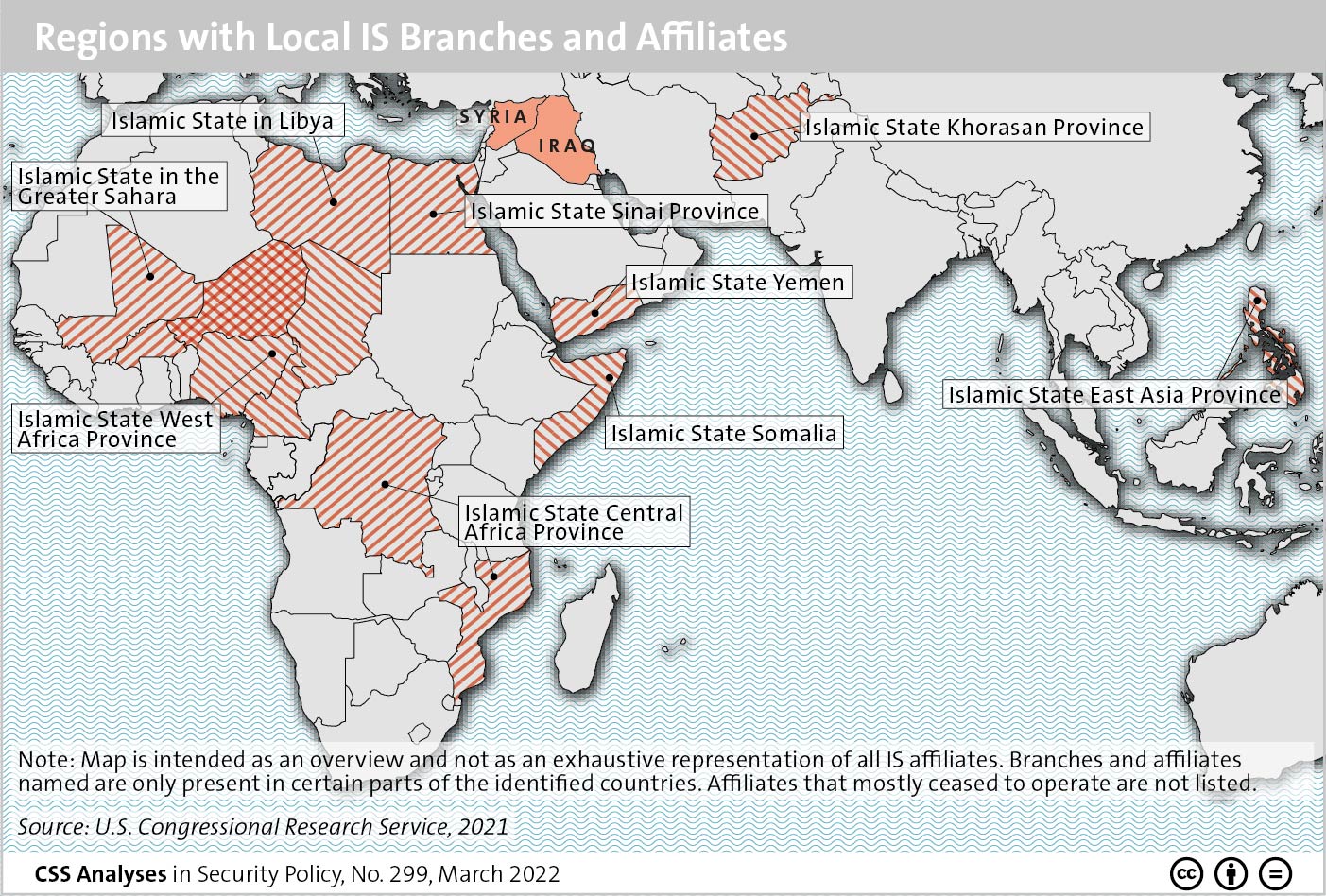

This week’s featured graphic shows the core IS’ state as of March 2022 as well as its affiliates in Africa, the Middle East and Asia. For a deeper assessment of the danger the IS still poses, read Fabien Merz’ CSS Analysis in Security Policy here.

This week’s featured graphic shows the core IS’ state as of March 2022 as well as its affiliates in Africa, the Middle East and Asia. For a deeper assessment of the danger the IS still poses, read Fabien Merz’ CSS Analysis in Security Policy here.

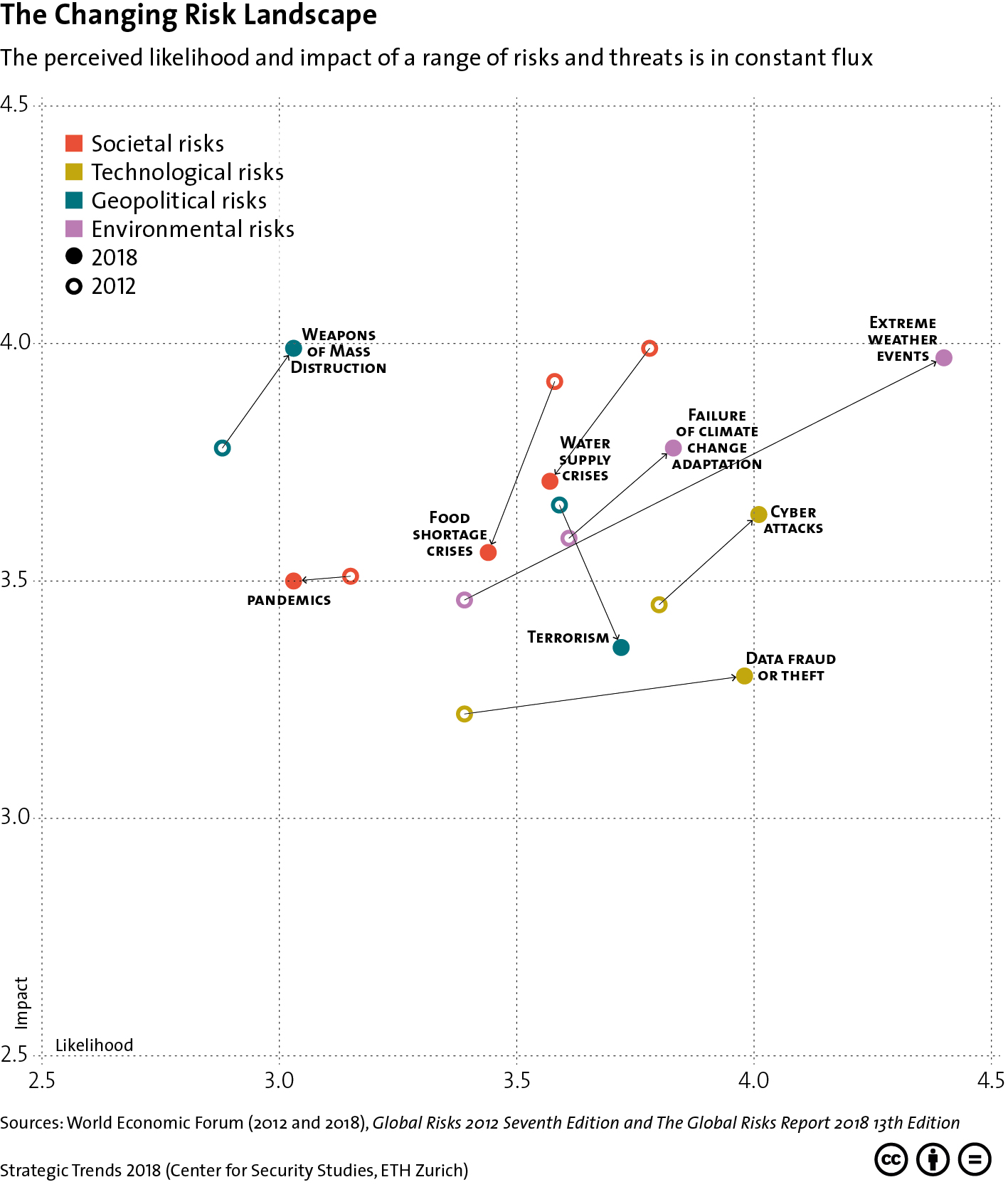

This graphic plots the change in the perceived likelihood and impact of various societal, technological, geopolitical and environmental risks between 2012 and 2018. For more on resilience and the evolution of deterrence, see Tim Prior’s chapter for Strategic Trends 2018 here. For more CSS charts, maps and graphics on risk and resilience, click here.

This article was originally published by War on the Rocks on 20 April 2017.

At approximately 2:40 in the afternoon of March 22nd, British-born Khalid Masood — a violent criminal who had previously been investigated by MI5 for links to extremists — deliberately drove into pedestrians making their way across Westminster Bridge. He killed a mother on her way to collect her children from school, a pensioner, and two tourists. After crashing the rented vehicle into the gates of Parliament, Masood ran into New Palace Yard and stabbed an unarmed policeman to death before being shot and killed by plainclothes officers. In contrast to other recent attacks in Western nations, which have frequently (sometimes incorrectly) been labeled acts of “lone-actor” terrorism, Masood’s assault was followed by a volley of articles with titles such as “Remote-Control Terror,” “Don’t Bet on London Attacker Being a Lone Wolf,” and “The Myth of the ‘Lone Wolf’ Terrorist.” Analysts were keen to point out that “lone-actors” are very rarely truly alone and that instead they tend to emerge from within broader, extremist milieus. Moreover, what sometimes seems like lone-actor terrorism at first glance turns out to be connected to, if not directed by, foreign terrorist organizations. Yet the official word on Masood is that, regardless of his associations, he acted “wholly alone.” To accurately understand the nature of terrorism today, patient, measured analysis and consistent use of terminology are necessary. It is therefore important to re-examine the concept of lone-actor terrorism and to try and appreciate where it fits within the overall spectrum of jihadist terrorist activity in the West.

Many, if not most “lone-actor” jihadists (including Masood), are indeed connected to other extremists and terrorists in some shape or form. Such connections have been greatly facilitated by the growth of social media and encrypted communication applications, which have also enabled the rise of virtual “planners” or “entrepreneurs” and so-called “remote-controlled” or “enabled” attacks, such as those in Würzburg and Ansbach, Germany, in July last year. Moreover, the number of jihadists with bona fide connections to foreign terrorist organizations, including training and combat experience abroad, has risen sharply since the outbreak of conflict in Syria and Iraq. Western security services are currently bracing for a potential surge in the number of returning foreign fighters.

This article was published by the Institute for Strategic, Political, Security and Economic Consultancy (ISPSW) in February 2017.

In mid-December, people and families all over Europe and in many parts of the world were gearing up to celebrate Christmas, one of the most important events in the Christian calendar. But on 19 December 2016 at 20:02 local time, a hijacked truck veered into a traditional Christmas market next to the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church in Berlin, Germany. Twelve people were killed. Four days later, the suspected perpetrator was shot and killed by police on an Italian plaza in Sesto San Giovanni, a suburb north of central Milan, Italy.

On the same day, ISIS extremists released a video of the perpetrator, filmed recently in Berlin. His name was Anis Amri. Having pledged allegiance to the group, he suggested that the Berlin attack was vengeance for coalition airstrikes in Syria.

This article was originally published by The European Union Institute for Security Studies (EUISS) on 4 May 2016.

As an international actor, the EU can expect to win enemies as well as admirers. Two recent terrorist attacks in close succession – the first targeting an EU military mission in Bamako, the second in the ‘EU quarter’ in Brussels – seemingly confirm this. They also lend weight to the argument that if member states want the EU to be a robust international actor, they must give it the counterterrorist powers to protect itself. But is the EU facing a classic terrorist logic of action-and-reprisal and, if not, what exactly is the EU’s risk profile?

A player and a pole

On 22 March, bombs were detonated in the public area of Brussels Zaventem airport, raising concerns about the vulnerability of Europe’s interconnected infrastructure networks – a particular preoccupation of the European Commission. Already last year, the Thalys train was the subject of two terror scares, showing that Islamists are ready to disrupt Europe’s transport systems. Now it has emerged that the perpetrators may have been eyeing harder infrastructure targets across Europe, including such critical infrastructure as nuclear power plants.

Another bombing occurred in Brussels that day, in a metro station serving the EU quarter. Although at least one of the attackers had been employed in an EU institution (as a cleaner) there is no evidence that the terrorists were directly targeting EU buildings or personnel. But, as Islamist media feeds now boast about having ‘attacked the heart of Europe’, the seed of an idea may well have been planted. Indeed, there are indications that the terrorists had been scoping the city’s diplomatic buildings (choosing the metro only because of the crowds and softness of the target).