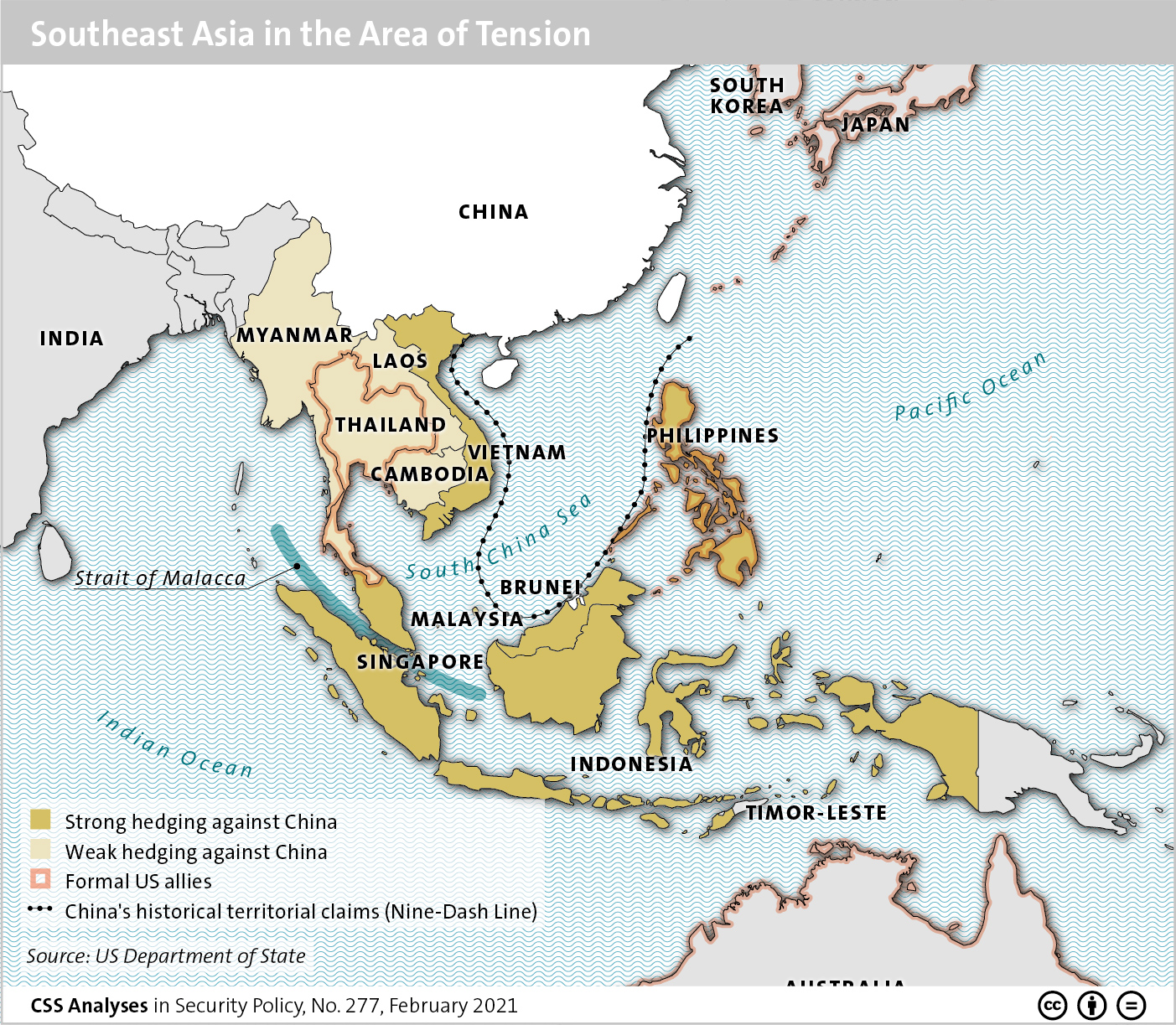

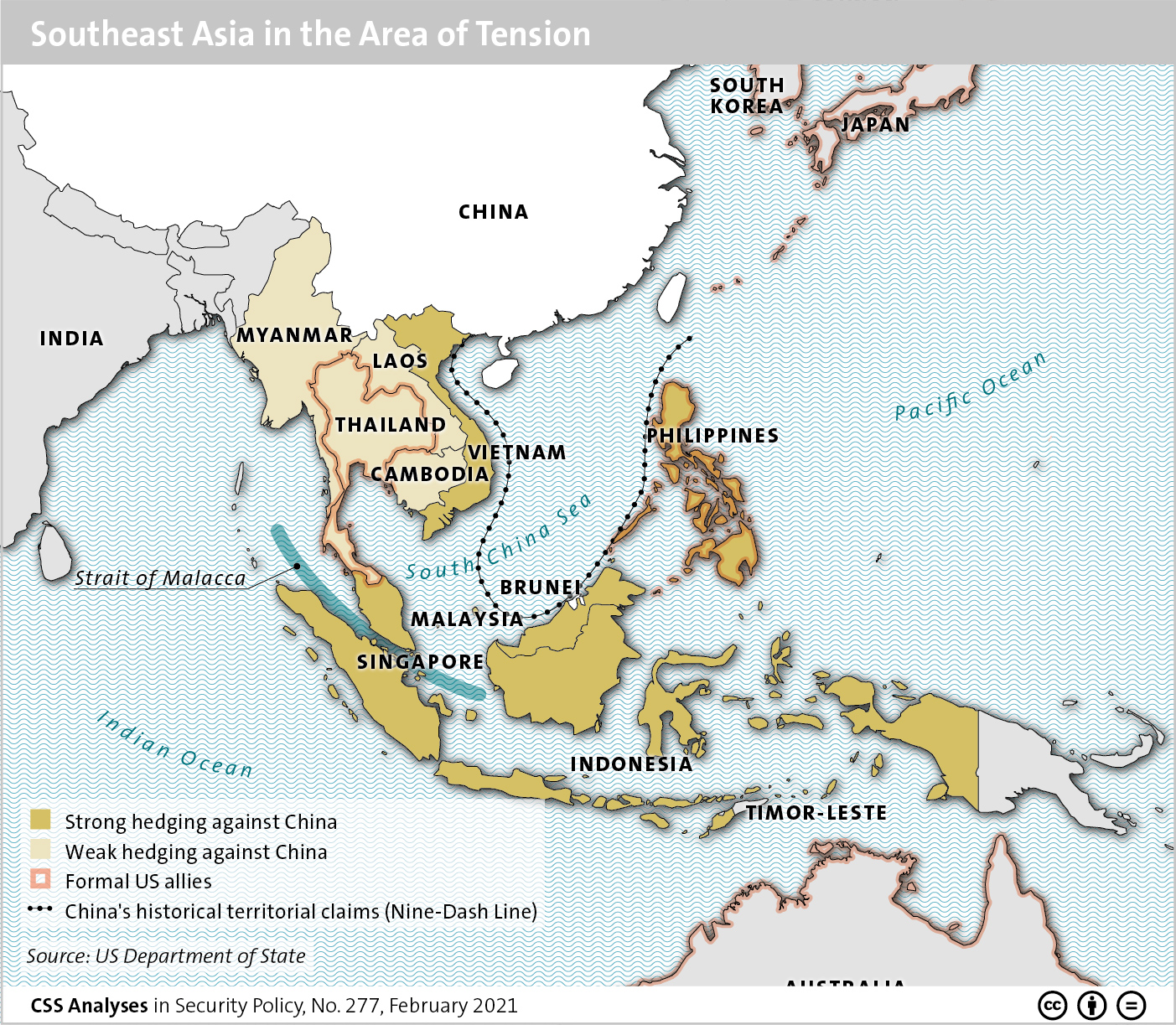

This week’s featured graphic maps Southeast Asia in the area of tension. For more on China-US rivalry in Southeast Asia, read Linda Maduz and Simon Stocker’s CSS Analyses in Security Policy here.

This week’s featured graphic maps Southeast Asia in the area of tension. For more on China-US rivalry in Southeast Asia, read Linda Maduz and Simon Stocker’s CSS Analyses in Security Policy here.

Bild: Lawrence Broadnax/DVIDS

Bild: Lawrence Broadnax/DVIDS

Dieser Blogbeitrag gehört zur Coronavirus-Blog-Reihe des CSS, die einen Teil des Forschungsprojektes zu den sicherheitspolitischen Implikationen der Corona-Krise bildet. Weitere Informationen finden Sie auf der CSS-Sonderthemenseite zur Corona-Krise.

Südostasien ist ein Brennpunkt in der strategischen Rivalität zwischen China und den USA. Was sich auf globaler Ebene abzuzeichnen beginnt, ist in dieser Weltregion bereits Realität: In einem wachsenden Konflikt konkurrieren China und die USA mit wirtschaftlichen, diplomatischen und teils militärischen Mitteln um Einflussnahme und versuchen die Machtbalance zu ihren Gunsten zu verändern. Dabei fördern sie kollidierende politische Initiativen und Ordnungsvorstellungen. Auch die Möglichkeit einer militärischen Auseinandersetzung rund um die Krisenherde im Südchinesischen Meer scheinen beide Seiten zunehmend in Kauf zu nehmen. In Südostasien verstärkt die Corona-Krise geopolitische Machtverschiebungen und politische (Neu-)Ausrichtungen.

This article was originally published by the East-West Center (EWC) in January 2020.

Southeast Asia is witnessing major changes to its political, strategic and economic fabric. Some of these, such as the rise of China, have been anticipated for some time, while others, such as the US-China trade dispute, the growing prominence of the Indo-Pacific as a strategic concept, and the Trump administration’s retreat from liberal internationalism, have unfolded rapidly and disruptively during the past few years.

This article was originally published by the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS) on 16 March 2017.

Synopsis

Human factors such as complacency and lack of questioning attitude have been identified as key contributors to the Fukushima nuclear disaster. But six years after the incident, East Asian states have yet to address human factors to make nuclear energy safe and secure in the region.

Commentary

JAPAN COMMEMORATED the sixth anniversary of the Fukushima-Daiichi nuclear disaster on 11 March 2017. Since the tsunami–triggered disaster, qualified observers assess that the biggest risk associated with nuclear power comes not from the technology of the infrastructure but from human factors. The Fukushima incident must be regarded as a technological disaster triggered not just by “unforeseeable” natural hazards (earthquake, tsunami), but also human errors.

Comprehensive reports on Fukushima, including findings made by the Japanese parliament and the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), examine how human factors such as the complacency of operators due to ‘safety myth’, the absence of regulatory independence from the nuclear industry, and reluctance to question authority all contributed to the “accident”. The Fukushima incident, like others before it, accentuates the utmost importance of addressing human and organisational factors so as to prevent nuclear accidents from occurring, or mitigate their consequences if they do occur.

This article was originally published by RSIS on 8 March 2016.

Synopsis

Australia’s 2016 Defence White Paper may indicate a future strategic policy of reactionary assertiveness with significant consequences for Southeast Asia’s security, especially in the South China Sea.

Commentary

DESCRIBED AS ‘clear eyed and unsentimental’ by Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull, Australia’s 2016 Defence White Paper (DWP) reaffirms Australia’s strategic attention towards maritime Southeast Asia. While the 2009 and 2013 DWPs also had this focus, the 2016 DWP bluntly expresses Australia’s concerns over this area.

In the 190-page long document, Canberra pledges to increase capital investment in defence capabilities from the current AUD 9.4 billion to AUD 23 billion in 2025-26, mostly in the maritime domain. The concern is less what Australia will do with this investment than the consequences it will potentially bring to Southeast Asia, and its ASEAN grouping, in light of Australia’s reactionary assertiveness against China’s maritime ambitions in the South China Sea.