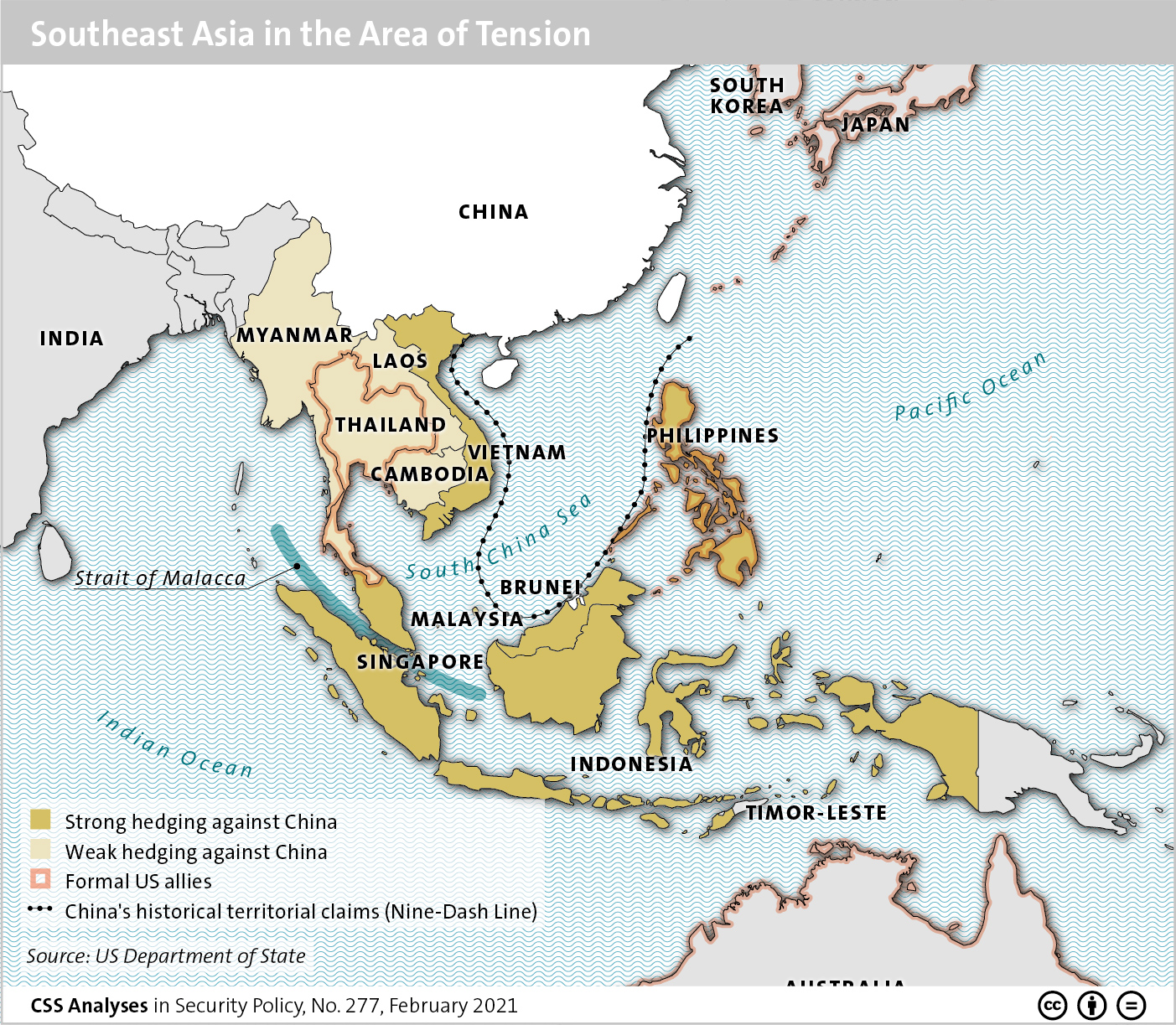

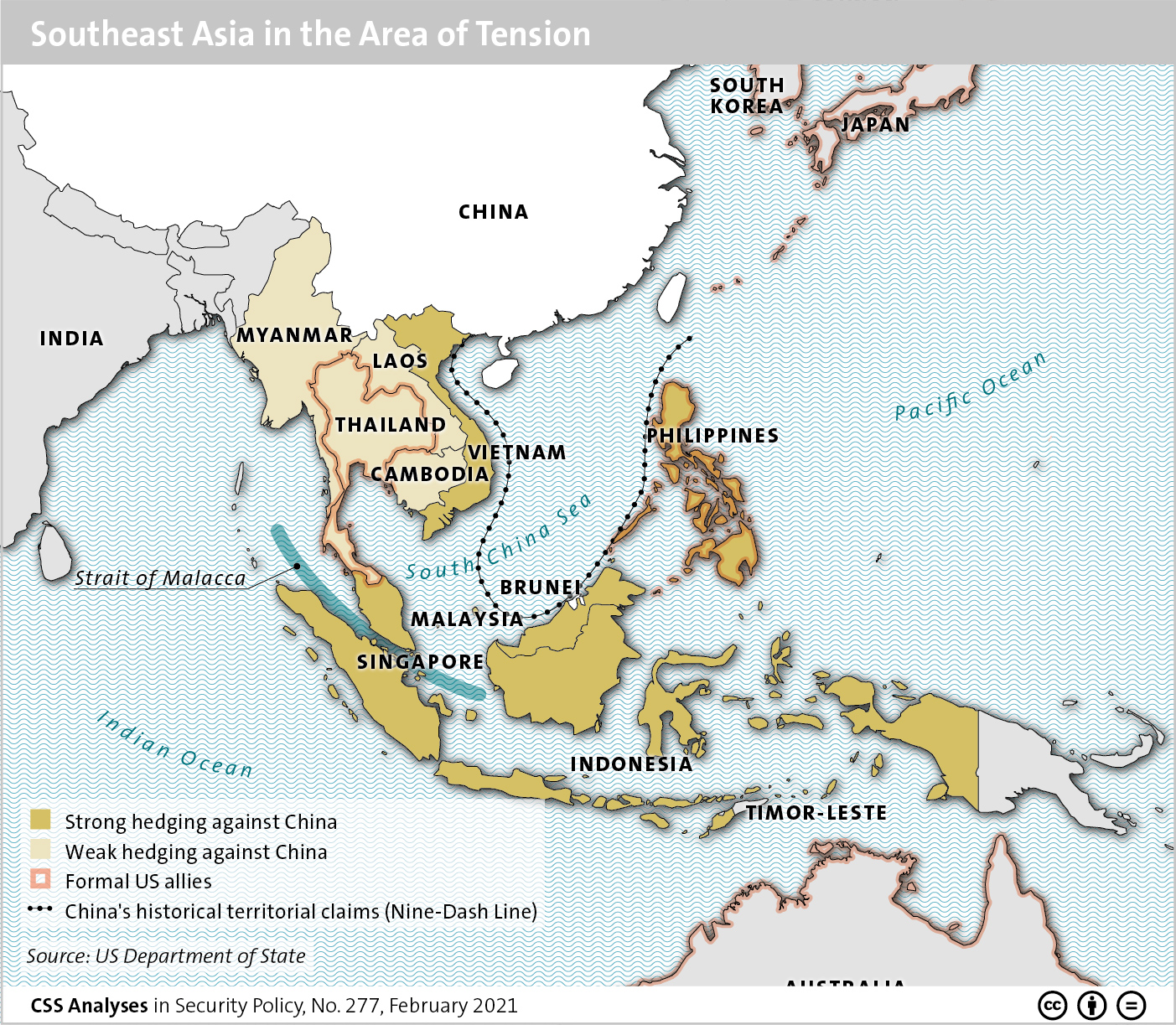

This week’s featured graphic maps Southeast Asia in the area of tension. For more on China-US rivalry in Southeast Asia, read Linda Maduz and Simon Stocker’s CSS Analyses in Security Policy here.

This week’s featured graphic maps Southeast Asia in the area of tension. For more on China-US rivalry in Southeast Asia, read Linda Maduz and Simon Stocker’s CSS Analyses in Security Policy here.

This article was originally published by the East-West Center (EWC) on 28 March 2017.

Russia’s policies regarding the South China Sea (SCS) dispute are more complex than they might seem. Moscow’s official position presents Russia as an extra-regional actor with no stakes in the dispute. According to the Russian Foreign Ministry, Russia “had never been a participant of the South China Sea disputes” and considers it “a matter of principle not to side with any party.” However, behind the façade of formal disengagement are Russia’s military build-up in the Asia-Pacific region, and the multi-billion dollar arms and energy deals with the rival claimants. These factors reveal that even though Moscow may not have direct territorial claims in the SCS, it has strategic goals, interests, and actions that have direct bearing on how the SCS dispute evolves.

One-fourth of Russia’s massive military modernization program through 2020 is designated for the Pacific Fleet, headquartered in Vladivostok, to make it better equipped for extended operations in distant seas. Russia’s military cooperation with China has progressed to the point that President Putin called China Russia’s “natural partner and natural ally.” The two countries’ most recent joint naval exercise – “Joint Sea 2016” – took place in the SCS, and became the first exercise of its kind involving China and a second country in the disputed SCS after the Hague-based tribunal ruling on China’s “nine-dash line” territorial claims. However, Russia’s relations with Vietnam are displaying a similar upward trend: Russia-Vietnam relations have been upgraded to a “comprehensive strategic partnership” comparable to the Russia-China relationship. Russia and Vietnam are developing joint gas projects in the SCS, and Moscow also is trying to return to the Cam Ranh naval base and selling Hanoi advanced weapon systems that enhance Vietnam’s defense capabilities.

This article was originally published by the Political Violence at a Glance on 21 September 2016.

Recent events demonstrate how difficult territorial disputes are to manage. In July a United Nations tribunal ruled that China’s sovereignty claims over the South China Sea, and its aggressive attempts to enforce them, violate international law. China’s response has been to ignore the Tribunal’s decision and continue its militarization of the Spratly Islands. Neighbors, including Vietnam, Malaysia, Brunei, and the Philippines, all challenge Chinese authority and reject its nine-dash line, but all also seem fearful of provoking an incident with Chinese forces. The US, while officially neutral when it comes to disputes over ownership of the South China Sea, could be drawn into any conflict that erupts. Not only does the US have an interest in protecting sea lanes that are vital to global commerce, but also its mutual defense treaty with the Philippines commits the US to assist Manila if a confrontation with China arises.

Territorial disputes, it turns out, are incredibly difficult to manage. Take the case of Kashmir, which appears to be heating up again as well. The killing of Burhan Wani, a leader in the Kashmir insurgency, on July 9, 2016, by Indian security forces has aggravated feelings of mistrust and apprehension. Pakistan’s Prime Minister, Nawaz Sharif, termed the killing “India’s barbarism” and declared the observance of a “black day” in Pakistan on July 19 in protest. India reacted by condemning Pakistan’s meddling in India’s internal affairs. Kashmir has been in dispute for nearly 70 years and the territorial disagreement seems unlikely to be resolved anytime soon. Indeed, India and Pakistan each continue to view the land as inviolable and thus not subject to negotiation. China’s control of approximately 20% of Kashmir further complicates settlement as well.

This article was originally published by the World Policy Institute on 9 March 2016.

In many public debates around the globe, the narrative of ‘”Arctic War” has become the predominant narrative of the future of Arctic security:

Driven by climate change, the Arctic ice cap is melting and large amounts of untapped oil and gas resources as well as lucrative shipping routes are becoming increasingly accessible. As a part of their response, Arctic states are making far reaching territorial claims in order to secure this tremendously rich treasure, and some, especially Russia, are emphasizing their regional ambitions by increasing their military capabilities in the High North. Trapped in an unavoidable arms race, the Arctic states are on a slippery slope toward military confrontation.

While advancing this narrative, supporters too easily apply interest-driven predictions of an uncontrollable arms race in the High North. Interestingly enough, one region seems to be exempted from this trend: the Arctic itself. This either means that the Arctic is “sleepwalking” into “unavoidable military escalation,” blinded by its long history of cooperation, or that it is worth taking a second look at the “narrative” of Arctic War.

Natural Resources, Territorial Claims, and Militarization?

First, what would be the source of a potential Arctic conflict? For many observers this seems to be very clear: economic interest. In 2008, a U.S. Geological Survey considered the Arctic to contain most of the world’s still undeveloped oil and gas. In addition, as the ice melts, lucrative shipping routes, like the Northwest Passage and the Northern Sea Route, are becoming more and more accessible. Since then, nearly every national submission to the extension of the Arctic state’s continental shelf (and thus the right to exploit the resources in the seabed) is considered a “provocative,” sometimes even “offensive” act.

This article was originally published by Strife on 25 May 2015.

Halfway between Japan and Taiwan are the the Senkaku Islands. They are claimed by Beijing under the name Diaoyu and by Taipei with the label Diaoyutai. The islands are prime real estate from a strategic perspective. Despite rumblings to the contrary, Tokyo seems to be sticking to her policy not to deploy ground troops on these islands. This is usually portrayed as a goodwill gesture, an olive branch extended to China, showing how Japan is ready to negotiate in good faith and how she does not see a military solution as the only possible outcome of the territorial dispute over the islands between China and Taiwan. This is a view supported by the mainstream media and many observers.

But China is keeping the pressure on the islands, with constant incidents featuring coastguard (and other state) vessels and trawlers entering Japanese territorial waters around them. And there is not much evidence of any attempt by Beijing to negotiate in good faith. This is in contrast to the approach taken by Taipei, which has reached a fisheries agreement with Tokyo, a practical implementation of President Ma’s East China Sea Peace Initiative.