Image courtesy of TheAndrasBarta/Pixabay.

This article was originally published by E-International Relations on 23 July 2020.

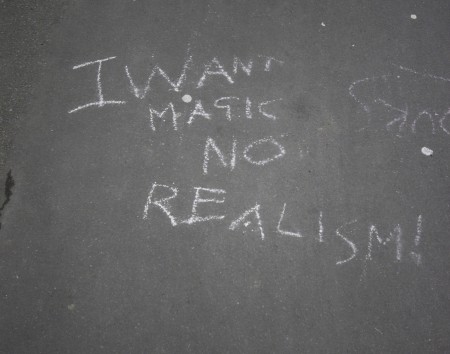

Realism’s dominance may be particularly pertinent at a time when International Relations’ Western-centrism is under renewed scrutiny and scholars and students call for the development of a more global International Relations (IR). This requires interrogating realism’s role in IR, how it may contribute to a more global IR, and what realism’s future holds. If realists forgo exploring new avenues to address this criticism, they may miss opportunities to contribute to a more global discipline and to better explain foreign policy and grand strategy beyond the West. Addressing its critics, realism can do useful things to develop a more global IR.