New interpretations of the foundational texts of a movement or ideology may be the most passive-aggressive form of intellectual combat. Done well, however, it can also be one of the most satisfying. A case in point: Arash Abizadeh’s article, “Hobbes on the Causes of War: A Disagreement Theory” in the May 2011 issue of the American Political Science Review.

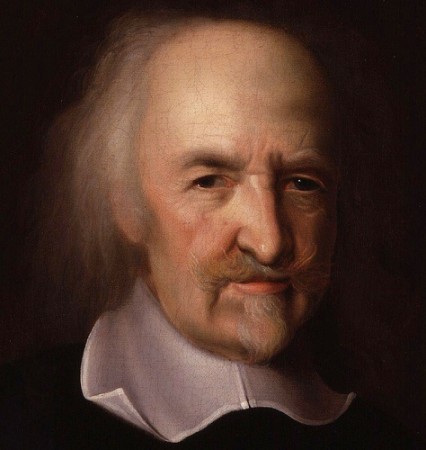

Academic schools always seem to have their prophets and sacred texts, but textual infallibility is rare. For the embattled Realist tribe, however, Hobbes’ Leviathan once came pretty close. Chapter XIII contains perhaps the most famous of all descriptions of human nature and its consequences for political life, that “without a common power to keep [us] all in awe … the life of man [is], solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short.” Everyone once knew (or thought they knew) what this meant. Indeed, the eloquence of this famous sentence once left many with little doubt: at least for Hobbes if not always for us, coercive power is the primary good. In its absence (as in international politics), ‘force and fraud’ are the two primary virtues.

But as Abizadeh points out, the ground has begun to shift beneath Realists’ feet. It has already been demonstrated, he tells us, that the chief function of Hobbes’ sovereign is to provide an “authoritative mechanism for governing” not conflicting wants, desires and interests, but “moral language,” — which would locate the source of war even for Hobbes at the level of “ideology, culture and socialization,” rather than systemic-structural incentives or depraved human nature.