This article was originally published by E-International Relations (E-IR) on 20 February 2016.

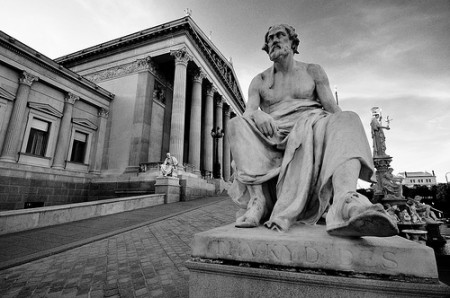

According to Max Weber, realism ‘recognizes the subjugation of morality’ to the ‘demands of [a] human nature’ in which the ‘insatiable lust for power’ is paramount (Weber in Smith 1982:1). This claim has led many—especially among liberal theorists—to label it as an amoral and bellicose doctrine (Molloy 2009:107). Yet while ‘inconsistency among realist theories’ (Smith 1982:12) may lend truth to claims of amorality and bellicosity among other strands of realism, this essay specifically examines the morality outlined in the realist works of Hans Morgenthau. It will argue that Morgenthau’s realist doctrine is neither amoral nor bellicose because it is informed by a set of utilitarian ethics that ‘rationally direct the irrationalities’ of human nature and aim to prevent major conflict (Niebuhr in Whitman 2011). The essay will begin by defining realist morality according to Morgenthau, focusing on ‘the evil of politics,’ the ‘moral precept of prudence,’ and ‘utilitarian ethics’ (1985:8). Though few critics dispute the presence of morals in Morgenthau’s realism, the essay will follow by addressing perceived flaws in his moral argument, as well as briefly examining the different moral assumptions made other strands of realist thought. The essay will conclude by restating the morals of ‘political ethics’ according to classical realism and end with a question concerning the significance of realist ethics to Weber’s ‘moral problem’ in International Relations (Smith 1982:28).

Hans Morgenthau is one of the most influential realist theorists of all time, and his arguments are fundamentally based in a ‘stern, utilitarian morality’ (Kaufman 2006:25); Morgenthau’s classical realism forms the basis for the argument put forth in this essay. According to critic Robert Kaufman, Morgenthau’s realism was developed as a ‘pessimistic critique of liberal utopianism,’ wary of the idealism of the inter-war years and intent on preventing another World War (2006:24). As such, Morgenthau puts forth a theory in which international relations are assumed to be at the mercy of human nature, self-interest, and an insatiable lust for power (1945:2). These factors, according to Morgenthau, are evidence that politics ‘falls within the domain of evil’ and thus, political ethics must be ‘the ethics of doing evil’ (1945:17). However, what seems a bleak and amoral outlook on world politics is redeemed by a moralist caveat: Though ‘the evil of politics is inescapable,’ by weighing the consequences of potential political action the ‘moral strategy of politics’ can be reduced to a choice among the least of all evils’ (Molloy 2009:99). Thus, despite his focus on power and successful political action, Morgenthau’s realism displays an inherent morality. Morgenthau’s realism is fundamentally concerned with mitigating the effects of a savage human nature on world order (1945:6).