Ten years ago, people were going long on Europe. In 2002, an influential article in Policy Review described Europe as “entering a post-historical paradise of peace and relative prosperity,” even “the realization of Kant’s Perpetual Peace.” Those familiar with that article, Robert Kagan’s “Power and Weakness,” know that this was praise of a certain kind. What made this Europe possible, according to Kagan was, actually: “the United States… mired in history, exercising power [out] in the anarchic, Hobbesian world.” Though Kagan clearly did not believe that Europe circa 2002 was an illustration of Kant’s vision of human progress in history — in which the working out of our “unsocial sociability” would eventually lead to a global alliance of peaceful republics — it was the image he used. And it was a compelling one.

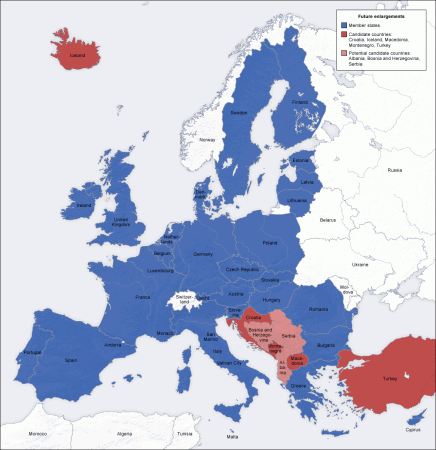

When that article was written, the idea of Europe as paradise was plausible. The Euro had just entered circulation, membership of the EU was about to reach for the first time behind the old iron curtain, and people were getting used to the prospect of Europe as a second superpower alongside the United States. Perhaps Kagan’s article was so influential because it suggested what few at the time believed: that what Europe had achieved in preceding decades would not easily or inevitably be repeated elsewhere in the decades to come, that European advances were themselves contingent and fragile. That power was not obsolete.

But however prescient Kagan’s insight, his article had a clear ideological charge. Many of his observations were simply applications of the principle that international behavior is determined by the relative distribution of state power. In Europe, if “the age-old laws of international relations” had been temporarily suspended it was because American power was great enough to compensate for European ‘weakness.’ The real Europe (Europe ‘at equilibrium’), he implied, was the one Mearsheimer feared imminent in the closing hours of the Cold War, with a re-unified Germany aspiring again to hegemony and in which “Soviet power could play a key role in balancing against Germany and in maintaining order in Eastern Europe.”

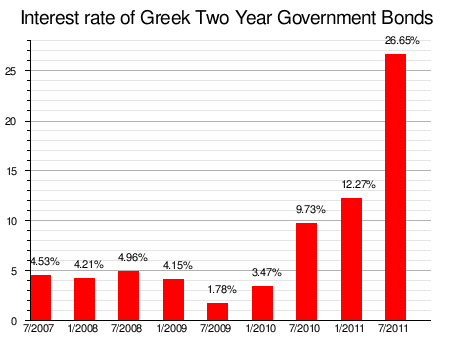

In 2011, few would call Europe paradise or utopia. A few weeks ago, London was literally burning with unrest; youth unemployment in Spain is still 40%, exceeding that of revolutionary Egypt; and, even if the ‘Lehman moment’ of a Greek sovereign default was averted earlier this summer, the Euro still hangs precariously in the balance (as the latest 10-year bond spreads indicate). The collapse or debauch of the currency would be a spectacular catastrophe in itself, but could have dramatic implications for the ‘stability of the region’ — and this is Western Europe we’re talking about.

Updating the neo-realist perspective to today’s more troubled climate, Sebastian Rosato (in the Spring issue of International Security) sees these developments as further evidence of the centrifugal effect that the absence of Soviet power has been having on Europe for decades. Further political or military integration was never seriously attempted after the Cold War ended and now that the economic benefits of integration are disappearing, few incentives remain. Though Rosato stops short of suggesting that “Europeans will cease cooperating with each other,” the current distribution of power means that the EU cannot survive in its current form: “as time passes, it is likely to look more like other international institutions, and less like the exceptional case that it seemed to be for so long.”

Others are even less sanguine. Robert Haas recently reminded us that Europe, thankfully, no longer matters geopolitically; that it is no longer an area of serious military-political concern and that its current troubles are insignificant by historical standards. But the end of this European exceptionalism could also mean the end of the new Europe and a step back towards the old. Those who at the time recklessly called for Greece to default — so as to’ destroy Brussels’ illusions’ — might have been more circumspect. For, as Kagan wrote back in 2002:

“the new Europe is indeed a blessed miracle and a reason for enormous celebration – on both sides of the Atlantic. For Europeans, it is the realization of a long and improbable dream: a continent free from nationalist strife and blood feuds, from military competition and arms races… something to be cherished and guarded, not least by Americans, who have shed blood on Europe’s soil and would shed more should the new Europe ever fail.”