This article was originally published by the World Policy Blog on 28 September 2017.

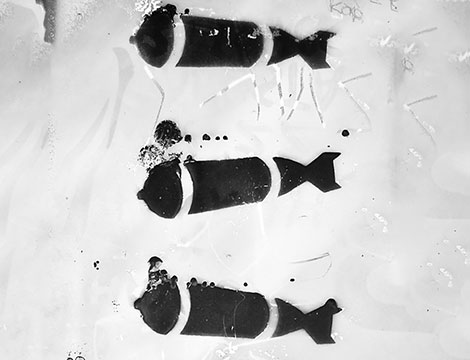

As the rhetoric and warlike maneuvers of the U.S. and North Korea accelerate, the media are increasingly considering the prospect of “accidental” war between the U.S. and North Korea. But if war does start, it will not be accidental. It depends on deliberate choices by both sides about whether to escalate violence or pull back and reassess. Those choices are made by politicians, who are often swayed by domestic political pressures.

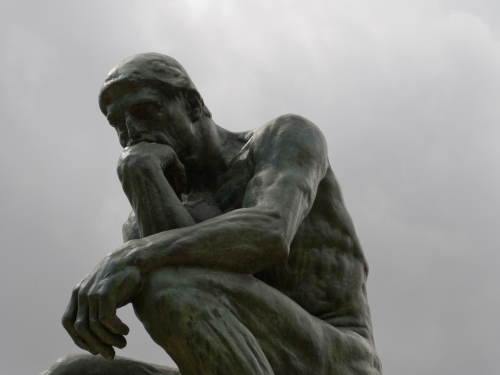

The myth of accidental war is a pernicious consequence of liberal international relations theory, which argues that since the consequences of war are so horrendous, no sane person would willfully choose war. Therefore, war occurs only when “madmen,” like Hitler, are in power, or when otherwise rational leaders miscalculate the consequences of their actions. My blog last week argued that the U.S. may be slipping into war with North Korea, but it is important to understand that if it does happen, it is not accidental. It is a product of choices being made now that people and leaders need to be responsible about.