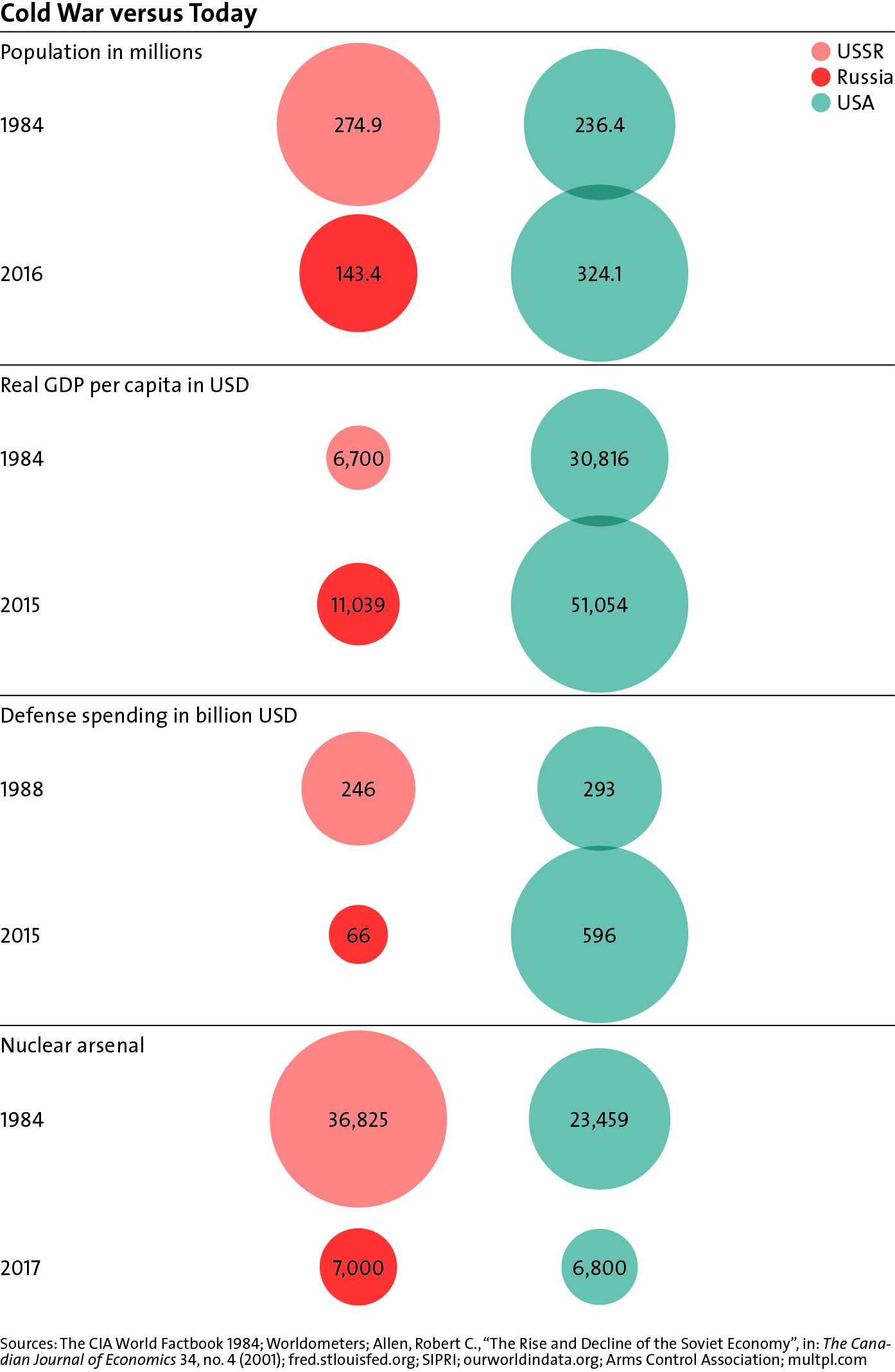

This graphic shows how the USSR compared to the US in terms of population, real GDP per capita (USD), defense spending (in billion USD) and nuclear weapons in the 1980s, as well as how the US compares to Russia in these key areas today. For an analysis of how different interpretations of the recent past still affect West-Russia relations and what is needed to rebuild trust, see Christian Nünlist’s chapter in Strategic Trends 2017 here. For more CSS charts and graphics, click here.

Tag: Balance of power

This article was originally published by E-International Relations (E-IR) on 8 May 2017.

Realism’s theoretical dominance in International Relations (IR) – especially its focus on the power of superpowers and its state-centric view of international society – has been challenged by the collapse of the Soviet Union and the global transformations characterising the post-Cold War era. One of those transformations is the way in which “states neither great nor small” are gaining increased recognition amid the disruptive multi-polarity of the current global disorder. Scholars such as Martin Wight and Carsten Holbraad, whose earlier writings about middle powers were overlooked in mainstream IR, are now acknowledged for their scholarly prescience. Bringing middle powers back into mainstream IR theorising is obviously overdue. There are two problems in the theorising of middle powers in contemporary IR scholarship that obscure their positioning and potential in post-Cold War international politics: (1) its intellectual history has been neglected; (2) “middle power” itself is a vague concept.

This article was originally published by E-International Relations (E-IR) on 8 May 2017.

Realism’s theoretical dominance in International Relations (IR) – especially its focus on the power of superpowers and its state-centric view of international society – has been challenged by the collapse of the Soviet Union and the global transformations characterising the post-Cold War era. One of those transformations is the way in which “states neither great nor small” are gaining increased recognition amid the disruptive multi-polarity of the current global disorder. Scholars such as Martin Wight and Carsten Holbraad, whose earlier writings about middle powers were overlooked in mainstream IR, are now acknowledged for their scholarly prescience. Bringing middle powers back into mainstream IR theorising is obviously overdue. There are two problems in the theorising of middle powers in contemporary IR scholarship that obscure their positioning and potential in post-Cold War international politics: (1) its intellectual history has been neglected; (2) “middle power” itself is a vague concept.

The neglected intellectual history of middle powers

The ranking of states hierarchically (big, small, middle sized) is by no means a modern (or even post-modern) invention. In ancient China and classical Greece the organisation of political communities and their status relative to each other was of great interest to thinkers as diverse as the Chinese sage Mencius (?372-289 BCE or ?385-303 BCE), and the Athenian philosopher Socrates (469-399 BCE).

This article was originally published by E-International Relations (E-IR) on 8 May 2017.

Realism’s theoretical dominance in International Relations (IR) – especially its focus on the power of superpowers and its state-centric view of international society – has been challenged by the collapse of the Soviet Union and the global transformations characterising the post-Cold War era. One of those transformations is the way in which “states neither great nor small” are gaining increased recognition amid the disruptive multi-polarity of the current global disorder. Scholars such as Martin Wight and Carsten Holbraad, whose earlier writings about middle powers were overlooked in mainstream IR, are now acknowledged for their scholarly prescience. Bringing middle powers back into mainstream IR theorising is obviously overdue. There are two problems in the theorising of middle powers in contemporary IR scholarship that obscure their positioning and potential in post-Cold War international politics: (1) its intellectual history has been neglected; (2) “middle power” itself is a vague concept.

The neglected intellectual history of middle powers

The ranking of states hierarchically (big, small, middle sized) is by no means a modern (or even post-modern) invention. In ancient China and classical Greece the organisation of political communities and their status relative to each other was of great interest to thinkers as diverse as the Chinese sage Mencius (?372-289 BCE or ?385-303 BCE), and the Athenian philosopher Socrates (469-399 BCE).

This article was originally published by the Lowy Institute on 21 November 2016.

As the Trump juggernaut rolled across the US on election day, turning the political map red, anxious foreign leaders began to contemplate a new world order of a kind few had envisaged.

Could it be that Donald Trump, the quintessential change agent, would administer the last rites to Pax Americana, the US-led rules-based Western order that had prevailed since 1945, thereby achieving what China, Russia and legions of anti-American jihadists had failed to bring about?

German Defence Minister Ursula von der Leyen believes Donald Trump’s shock win signals the end of Pax Americana. Many others agree, among them former Australian foreign minister Bob Carr, who sees the failure of Barack Obama’s signature Trans-Pacific Partnership as ‘symbolic of the dismantling of the post-World War II order in which the US had sought a global leadership role’.