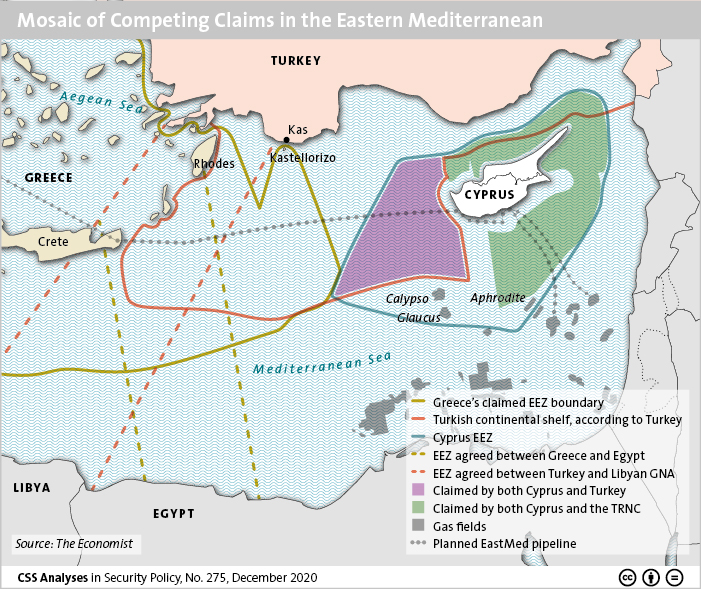

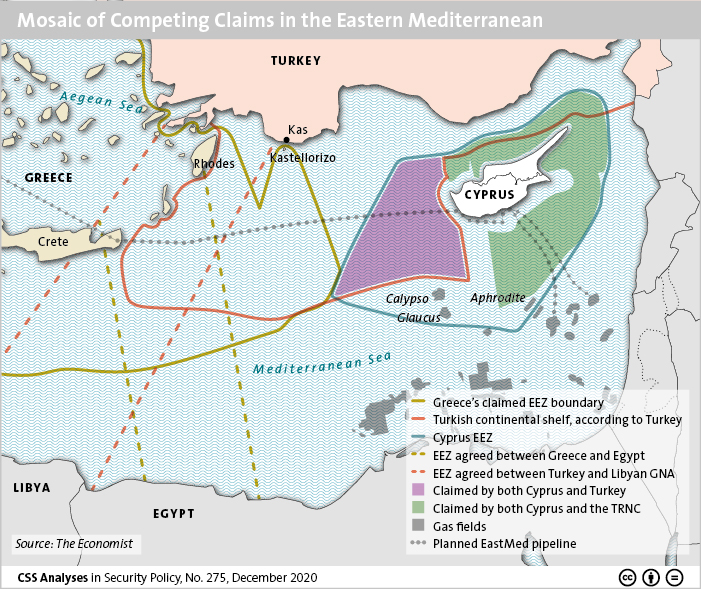

This week’s featured graphic maps the mosaic of competing claims in the Eastern Mediterranean as of December 2020. For more on Turkey and the Eastern Mediterranean, read Fabien Merz’s CSS Analyses in Security Policy here.

This week’s featured graphic maps the mosaic of competing claims in the Eastern Mediterranean as of December 2020. For more on Turkey and the Eastern Mediterranean, read Fabien Merz’s CSS Analyses in Security Policy here.

This article was originally published by War is Boring on 9 July 2016.

As the South China Sea heats up, one of Beijing’s most important tools — its Maritime Militia or “Little Blue Men,” roughly equivalent at sea to Putin’s “Little Green Men” on land — offers it major rewards while threatening the United States and other potential opponents with major risks.

When the Permanent Court of Arbitration in the Hague announces its rulings on the Philippines-initiated maritime legal case with China on July 12 — likely rejecting some key bases for excessive Chinese claims in the South China Sea — the Maritime Militia will offer a tempting tool for Beijing to try to teach Manila (and other neighbors) a lesson while frustrating American ability to calm troubled waters.

This major problem with significant strategic implications is crying out for greater attention, and effective response. Accordingly, this article puts China’s Maritime Militia under the spotlight to explain what it is, why it matters and what to do about it.

A ship built in Japan, owned by a brass-plate company in Malta, controlled by an Italian, chartered by the French, skippered by a Norwegian, crewed by Indians, registered in Panama, etc. etc. is attacked while transiting an international waterway in Indonesian territory. So – if the pirates ever get arrested – who exactly is in charge of prosecuting them?

Some legal scholars recommend that captured pirates should be prosecuted in the region where they are arrested. Unfortunately, countries that lack the capacity to secure their waters often also have limited resources for prosecution. If more than one country is interested in prosecuting the arrested pirates, it is not immediately clear which country’s judiciary system should be applied. The international legal framework remains vague and sometimes even contradictory. And it starts with the definition, around which there is no consensus: The UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) defines piracy as 1) an act of violence 2) conducted on the high seas 3) against another vessel 4) and for private gain; while the Convention for the Suppression of Unlawful Acts of Violence against the Safety of Maritime Navigation (SUA) defines it as 1) intentionally seizing or damaging a ship or 2) attempting to seize or damage a ship.

This week in New York, the state parties to the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) are meeting for the 21st time since the convention’s conclusion in 1982. Major items on the agenda are the reports of the ongoing work of the Convention’s three main organs: 1) the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (ITLS), which interprets the Convention and adjudicates disputes 2) the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS), which evaluates geological and oceanographic data, and 3) the International Seabed Authority (ISA), which organizes and controls activities related to the sea floor, which lies beyond national jurisdictions.

Three main items are currently before the Tribunal: a boundary dispute between Bangladesh and Myanmar in the Bay of Bengal (of special relevance to Conoco Phillips); the M/V Louisa case, a dispute arising from Spain’s detention since 2006 of the eponymous research vessel, which was flying the flag of St Vincent and the Grenadines in Spanish coastal waters while conducting scientific surveys of the sea floor; and a request for an advisory opinion from the Tribunal on the status of state parties sponsoring private activities on the sea floors outside national jurisdictions, a case arising from commercial activities proposed by Nauru Ocean Resources Inc. and Tonga Offshore Mining Ltd.

While these are hardly the issues making international headlines – and the above two companies remain unlikely, to say the least, to ever become major global players in natural resources – the Law of the Sea can be a genuine battleground of great power politics.

In the very year the International Maritime Organization (IMO) designated “Year of the Seafarer”, a new report, published by the Environmental Justice Foundation (EJF), has now exposed how illegal, ‘pirate’ fishing operators are ruthlessly exploiting not only the riches of the sea, but also the crews aboard the fishing vessels.

Pirate fishing – less prosaically known as illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing – is one of the most serious threats to the future of world fishery. Occurring in virtually all fishing grounds from shallow coastal waters to deep oceans, and driven by an enormous global demand for fish and seafood, pirate fishing is leaving coastal communities in developing countries without much needed food and income and the marine environment debilitated and empty.

IUU fishing is an organized criminal activity, professionally coordinated and truly global, respecting neither national boundaries nor international attempts to manage the seas’ resources. It thrives where governance is weak and where countries fail to meet their international responsibilities. According to the EJF and Greenpeace, it is thus not surprising that most illegal fishing is carried out by ships flying so-called ‘flags of convenience’.