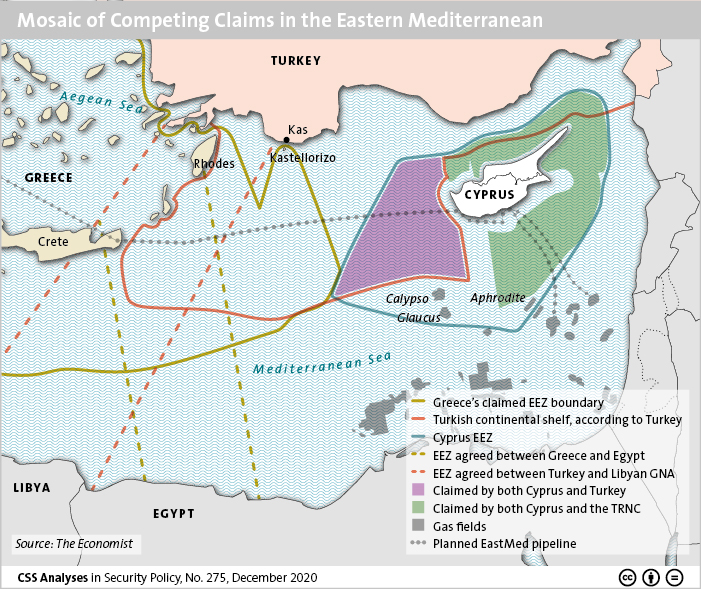

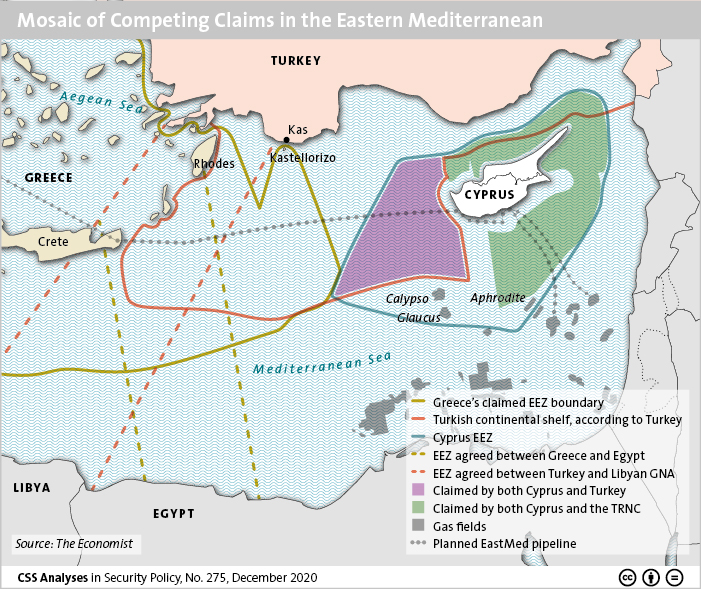

This week’s featured graphic maps the mosaic of competing claims in the Eastern Mediterranean as of December 2020. For more on Turkey and the Eastern Mediterranean, read Fabien Merz’s CSS Analyses in Security Policy here.

This week’s featured graphic maps the mosaic of competing claims in the Eastern Mediterranean as of December 2020. For more on Turkey and the Eastern Mediterranean, read Fabien Merz’s CSS Analyses in Security Policy here.

This article was originally published by the Elcano Royal Institute on 19 January 2017.

Summary

The reunification of Cyprus is one of the world’s longest running and intractable international problems. The latest talks in Geneva in January 2017 between Nicos Anastasiades, the Greek-Cypriot President, and Mustafa Akıncı, his Turkish-Cypriot counterpart, after 20 months of negotiations, made significant progress. The issues of territorial adjustments and security and guarantees are the most sensitive and core issues yet to be resolved and ones that will determine whether a solution can be reached and approved in referendums on both sides.

Analysis

Background

The Mediterranean island has been divided since Turkey’s invasion in 1974 in response to the Greek military junta’s backing of a coup against President Makarios aimed at enosis (union with Greece).1 Cyprus is the only divided country in Europe and its capital, Nicosia, is also split in two.

This article was originally published by Europe’s World on 11 Sepember, 2015.

There is no doubt that following the rise of Mustafa Akıncı to become the Turkish Cypriot leader this April, there have been high expectations for a resolution to the Cyprus problem. Nevertheless, it is important to be pragmatic and not underestimate the difficulties. For a real resolution, it is essential to achieve consensus on several major aspects of the problem.

First, there are serious constitutional disagreements between the two sides. The Greek Cypriot position is that the bi-zonal, bi-communal federation and the new partnership are an evolution of the Republic of Cyprus, which is recognised by all countries except Turkey. The Turkish Cypriot position is that the new partnership will involve a new state entity, to be created by two equal and sovereign constituent states. In terms of governance, the Greek Cypriots stress the importance of a unified state with a common society, economy and institutions. Turkish Cypriot positions revolve around entrenching a new situation based on ethno-communal lines. Bridging this gap will be difficult given that the positions reflect two fundamentally opposing philosophies. Furthermore, while the Turkish Cypriot positions are nearer to a confederation, or at best a very loose federation, the Greek Cypriots have in mind a federal arrangement with a rather strong government. It should be stressed that President Nicos Anastasiades himself may be willing to engage in a serious discussion about decentralisation provided he is satisfied on other issues such as territory and property.

This article was originally published by The Conversation on 9 January, 2015.

The calling of a snap election in Greece for January 25 has been met with great concern in political circles, prompted direct interventions by top European officials and alarmed markets and credit rating agencies.

This is all because Syriza, the Greek Coalition of the Radical Left, is being tipped to win the election. It is currently the largest opposition party in the Greek parliament and consistently leads the polls as the vote approaches.

According to the latest polls Syriza’s vote share could stretch anywhere between 36% to 40%, with the centre-right New Democracy trailing by at least three percentage points. Anything above 36% gives Syriza not only an electoral victory but an outright governing majority in the Greek parliament because the winning party is automatically handed a 50-seat bonus in the 300-seat parliament.

Opponents claim that Syriza would renege on Greece’s international obligations if it came to power and that efforts to reform the country would be halted. Political instability would ensue and the eurozone would again be plunged into crisis. Talk of Greece leaving the euro has been particularly prominent of late.

This article was originally published by SPERI on 13 August 2014.

The numbers speak for themselves. Though currently in opposition, both its plurality in European elections and recent polling suggest that Syriza (Coalition of the Radical Left) will soon become Greece’s largest political force. Only founded in March, Spain’s Podemos (We Can) took five seats and 8 per cent of the vote in May’s European elections. Its support now stands at 15 per cent, compared to 25 per cent apiece for the traditional parties. How did both manage it? Surprisingly, the answer is by emulating the Latin American left. Syriza leader Alexis Tsipras has undertaken numerous fact-finding missions to Venezuela over the past decade and considers Hugo Chávez a personal hero. Podemos, meanwhile, was established by a group of longstanding advisors to the governments of Bolivia, Ecuador and Venezuela, all based at Madrid’s Universidad Complutense. So central has their experience been that Podemos cite ‘thorough analysis and learning of recent Latin American processes’ as one cornerstone of their approach.