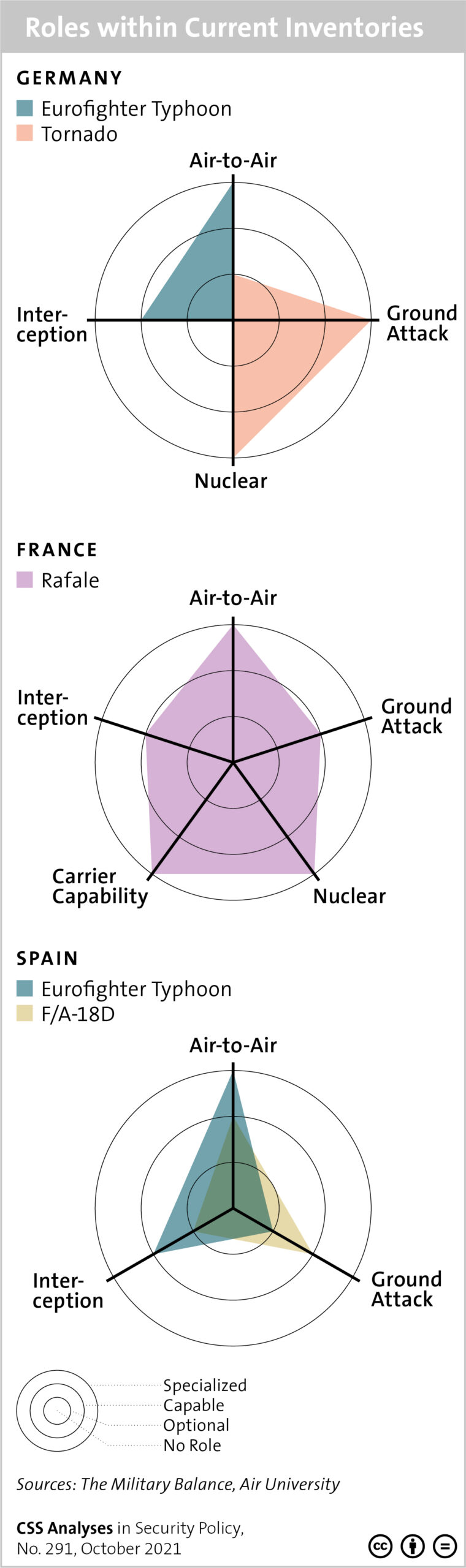

This week’s featured graphic shows the roles within the fighter jet inventories of Germany, France and Spain. For more on current developments of European fighter programs, read Amos Dossi and Niklas Masuhr’s CSS Analysis in Security Policy here.

This week’s featured graphic shows the roles within the fighter jet inventories of Germany, France and Spain. For more on current developments of European fighter programs, read Amos Dossi and Niklas Masuhr’s CSS Analysis in Security Policy here.

This article was originally published by the War on the Rocks on 12 August 2016.

From America’s first major overseas military intervention in 1801 against the Barbary States to today’s on-going military presence in the region, the United States has often relied on a tiny piece of the United Kingdom located in the Mediterranean Sea.

Gibraltar, commonly referred to simply as “the Rock,” is a rocky headland covering just over 2.7 square miles on the southern coast of the Iberian Peninsula. It is strategically located at the western entrance to the Mediterranean Sea, where the strait between Europe and Africa spans a mere 7.7 nautical miles at its narrowest point.

After being captured from the Moors in 1462, Gibraltar was part of Spain until it was captured in 1704 by a joint Anglo-Dutch-Catalan force during the War of the Spanish Succession. The Rock was formally ceded to the United Kingdom in 1713 as part of the Treaty of Utrecht “…forever, without any exception or impediment whatsoever.”

Since losing Gibraltar in 1704, the Spanish have sought to take it back. Examples abound through the last three centuries. They unsuccessfully laid siege to Gibraltar on three separate occasions in the 18th century and have since used a combination of military, diplomatic, economic, and plain harassing tactics in an attempt to get the Rock back. More recently, after the Gibraltarians approved a new constitution in 1969, Spain’s fascist dictator Francesco Franco closed the land border and blocked telecommunications between Spain and Gibraltar until the border was reopened in 1985.

Five years ago, the Basque militant group ETA (Basque Homeland and Freedom) announced a unilateral and permanent cessation of operations. Since then, the disappearance of political violence has given rise to a new debate on Basque nationhood: more inclusive, more open, more civic, and at the same time stronger in its affirmation of the legitimacy of popular sovereignty and the democratic demand to exercise ‘the right to decide’, as against the earlier radicalism of immediate independence.

A new book edited by Pedro Ibarra Güell and Åshild Kolås, Basque Nationhood Towards a Democratic Scenario, takes stock of the contemporary re-imagining of Basque nationhood in both Spain and France. Taking a fresh look at the history of Basque nationalist movements, it explores new debates that have emerged since the demise of non-state militancy. Alongside analysis of local transformations, the book also describes the impacts of a pan-European (if not global) rethinking of self-determination, or ‘the right to decide’.

This article was originally published by LSE EUROPP, a blog hosted by the London School of Economics and Political Science, on 2 October, 2015.

Catalonia’s independence movement secured a majority of seats in the regional parliament on 27 September, but fell short of winning an outright majority of the vote. The result strengthened the case for a referendum, which Madrid has for long rejected, but weakened the case for independence: after years of campaigning and mobilising Catalans, the pro-independence camp is still unable to secure half the regional vote.

The path to independence will remain a long, contentious and indeed controversial one. But what lessons can Spain draw from other secessionist movements around the world? The primary lesson is that secession, whether it takes place in Europe, the Middle East or Africa, in industrialised democratic countries or war-torn developing countries, tends to bring more problems than it solves.

This article was originally published by SPERI on 13 August 2014.

The numbers speak for themselves. Though currently in opposition, both its plurality in European elections and recent polling suggest that Syriza (Coalition of the Radical Left) will soon become Greece’s largest political force. Only founded in March, Spain’s Podemos (We Can) took five seats and 8 per cent of the vote in May’s European elections. Its support now stands at 15 per cent, compared to 25 per cent apiece for the traditional parties. How did both manage it? Surprisingly, the answer is by emulating the Latin American left. Syriza leader Alexis Tsipras has undertaken numerous fact-finding missions to Venezuela over the past decade and considers Hugo Chávez a personal hero. Podemos, meanwhile, was established by a group of longstanding advisors to the governments of Bolivia, Ecuador and Venezuela, all based at Madrid’s Universidad Complutense. So central has their experience been that Podemos cite ‘thorough analysis and learning of recent Latin American processes’ as one cornerstone of their approach.