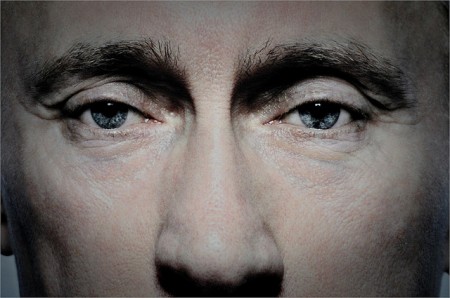

On 24 September, Russian Prime Minister Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin announced his decision to return to the presidency, a post he may now possibly occupy for a further two successive terms until 2024. Unfortunately, his election to the post seems to be a foregone conclusion. In previous polls, opposition candidates, anti-Kremlin parties, and other critics failed to even make it onto the ballot paper. And with Russian state TV having developed into a veritable Putin lovefest, he can expect blanket positive coverage ahead of a lofty coronation.

I am surely not the only one to feel reminded of the dark days of the Soviet period, when the General Secretary’s seat was passed from one frail, tottering character to the next, and political prognostication revolved solely around signs of imminent death – since death was the only thing that could open the door to real reform.

However, on closer examination, it hardly seems fair to compare Putin’s reign with the gerontocracy of the Soviet period, as the Soviets at least had a Politburo. Russia’s current transformation into what political scientists are calling a sultanistic or neo-patrimonial regime is a break from Russian history and the global trend toward democratization. The czars at least drew their legitimacy from their blood and their faith, and the General Secretaries owed their power to their party and their ideology, Putin’s rule, however, is based solely on the man himself.