First being used for surveillance, unmanned aerial vehicles (drones) were initially conceived in the early 1990s for reconnaissance and forward observation roles. However, by 2001, the United States started arming drones with missiles and using them in combat operations. Since then, more than 40 other states and entities are estimated to have acquired the drone technology, including Russia, China, Iran, and Israel.

The first known use of a drone to kill a particular individual occurred against Al- Qaeda’s Mohammed Atef in Afghanistan in November 2001. Later in November 2002, a suspected ‘lieutenant’ in Al-Qaeda was killed along with five other persons in a drone attack in Yemen, carried out by CIA personnel. In 2003, the UN special rapporteur concluded that the Yemen strike constituted a “clear case of extrajudicial killing”.

Within states, international human rights law prohibits governments from using excessive force against individual groups; governments may only resort to military force if an armed opposition involves significant force. The normal standards can be found in the UN Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement Officials. Despite this clear law, US officials argue that because the 9/11 attacks involved significant force, the US can target and kill Al-Qaeda members and other suspected terrorists and militants without warning, wherever they are found.

With regard to the use of drones, it is generally agreed that operations may be launched into the territory of another state with that state’s consent (with some exceptions). Examples of such include operations in which the consenting state (1) agrees on the basis of the other state’s right of self-defense, (2) invites the other state to assist with a non-international armed conflict (as in Afghanistan), (3) requests the other state’s assistance in complying with its obligation to police its own territory, or (4) seeks assistance with its own law enforcement operations against terrorists. In law enforcement operations, human rights law is applicable at all time.

It is legally more problematic when the cross-border operation is conducted without the territorial state’s consent, as the operation can then be construed as an act of war. In such cases, it is necessary to balance two competing legal rights – the territorial integrity of one state and the self-defense of the other.

The ORG Report

On 23 June 2011, the London-based think tank Oxford Research Group (ORG) published the report, “Drone Attacks, International Law, and the Recording of Civilian Casualties of Armed Conflict”. In it, the ORG conducts wide-ranging research into whether international legal obligations to record the civilian casualties of armed conflicts apply — or apply in a different manner than presently understood– to the drone attacks currently being conducted by the United States Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), particularly in Afghanistan, Pakistan and Yemen.

The report determines that:

- A Non-International Armed Conflict exists in Pakistan which is part and parcel of the Non-International Armed Conflict in Afghanistan.

- Those drone attacks that occur in the Northwest Frontier Province (officially Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa Province), and Federally Administered Tribal Areas are governed by the law applicable to Non-International Armed Conflict.

- There is an evolving armed conflict in Yemen, though it is not part of the CIA drone campaign.

- Drone attacks that take place in Yemen and in the areas of Pakistan not part of the Non-International Armed Conflict in Afghanistan are governed generally by domestic law and international Human Rights Law. The intended targets of drone attacks are by and large classified as civilians, except for those who at the time of attack are directly participating in a Non-International Armed Conflict.

- The United States, Pakistan, Yemen, and organized non-state actors all fall within the international legal obligation associated with civilian casualties.

- The legal obligations binding all of the participants in the drone attacks relevant to areas of armed conflict are:

- to search for all missing civilians as a result of hostilities, occupation or detention;

- to collect all of the casualties of armed conflict from the area of hostilities as soon as circumstances permit;

- if at all possible the remains of those killed are to be returned to their relatives;

- the remains of the dead are not to be despoiled;

- any property found with the bodies of the dead is to be returned to the relatives of the deceased;

- the dead are to be buried with dignity and in accordance with their religious or cultural beliefs;

- the dead are to be buried individually and not in mass graves;

- the graves are to be maintained and protected;

- exhumation of dead bodies is only to be permitted in circumstances of public necessity, which will include identifying cause of death;

- the location of the place of burial is to be recorded by the party to the conflict in control of that territory;

- there should be established in the case of civilian casualties an official graves registration service.

- Those attacks that take place outside of the geographical area of armed conflict are extra-judicial killings contrary to international Human Rights Law and domestic criminal law unless the persons involved were killed while trying to evade lawful capture;

- Those authorities responsible for the territory in which these extra judicial killing occur are responsible to investigate every incident of casualty and fulfill the same obligations as set out above in armed conflict

Clear Conclusions

The resulting examination of the facts of drone use, coupled with an analysis of relevant law resulted in a number of very clear conclusions:

- Because the status of the victim is so often contested or undetermined at the time of attack (and often for substantial post-attack periods), there cannot be separate recording requirements for combatants and civilians – every casualty must be properly identified post-attack.

- The universal right to life which specifies that no-one be “arbitrarily” deprived of his or her life cannot be seen to have been upheld unless the identity of the deceased is established – whether a casualty was the intended target or merely a person in the wrong place at the wrong time is critical.

- Reparations and compensation for possible wrongful killing, injury and other offenses also depend on full and proper recording of casualties and their identities.

- The responsibility to properly record casualties is a requirement jointly held by those who launch and control the drones and those who authorize or agree to their use.

- Non-state actors have a specific but still very real responsibility in this situation, which is to comply with their obligations to record civilian casualties with respect to areas under their control.

- A particular characteristic of drone attacks is that efforts to disinter and identify the remains of the deceased may be daunting, as with any high-explosive attacks on persons. However, this difficulty in no way absolves parties such as those above from their responsibility to identify all the casualties of drone attacks.

- Another characteristic of drone attacks is that as isolated strikes, rather than part of raging battles, there is no need to delay until the cessation of hostilities before taking measures to search for, collect and evacuate the dead.

The implications of these findings go well beyond the particularities of these weapons, these countries, and these specific uses. The legal obligations — enshrined as they are in International Humanitarian Law, International Human Rights Law, and domestic law — are binding on all parties at all times in relation to any form of violent killing or injury by any party. States, individually and collectively, thus need to plan how to work towards compliance with these substantial bodies of law.

Further Research by the British Bureau of Investigative Journalism

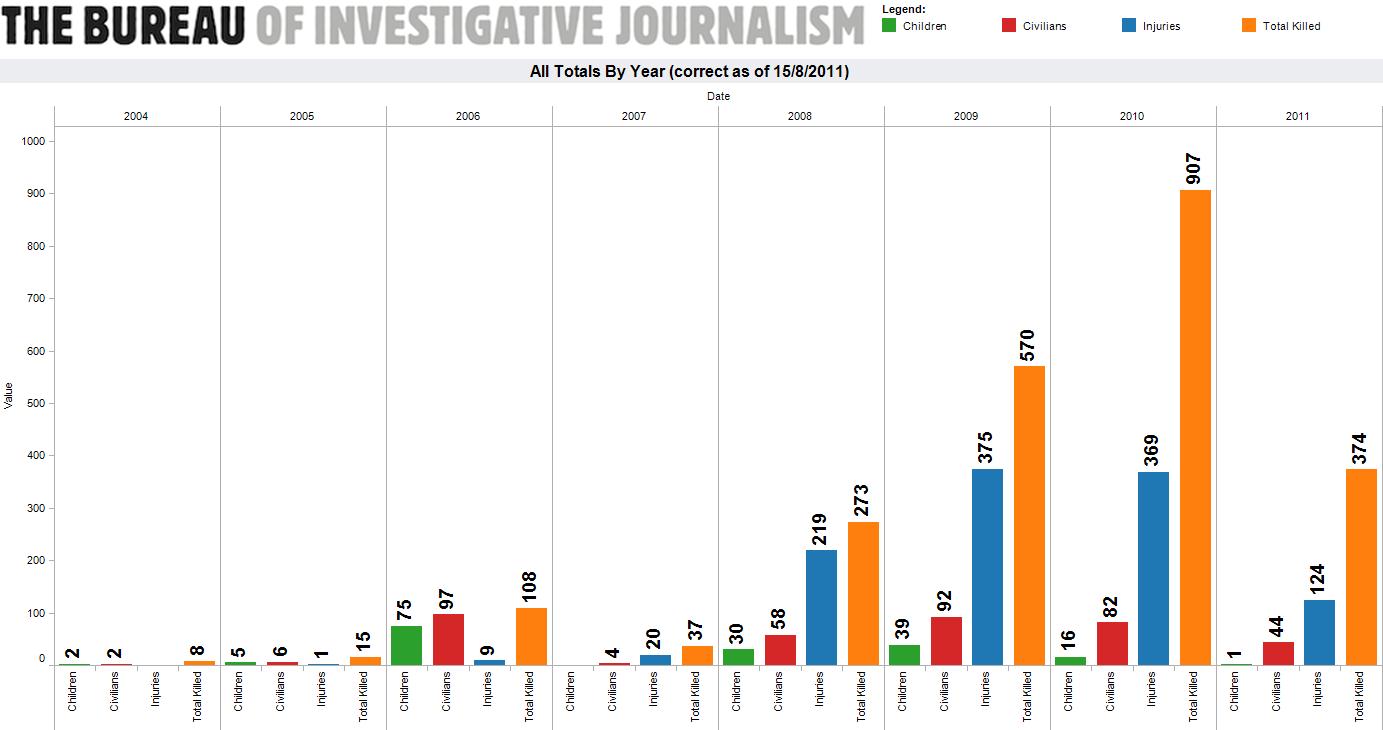

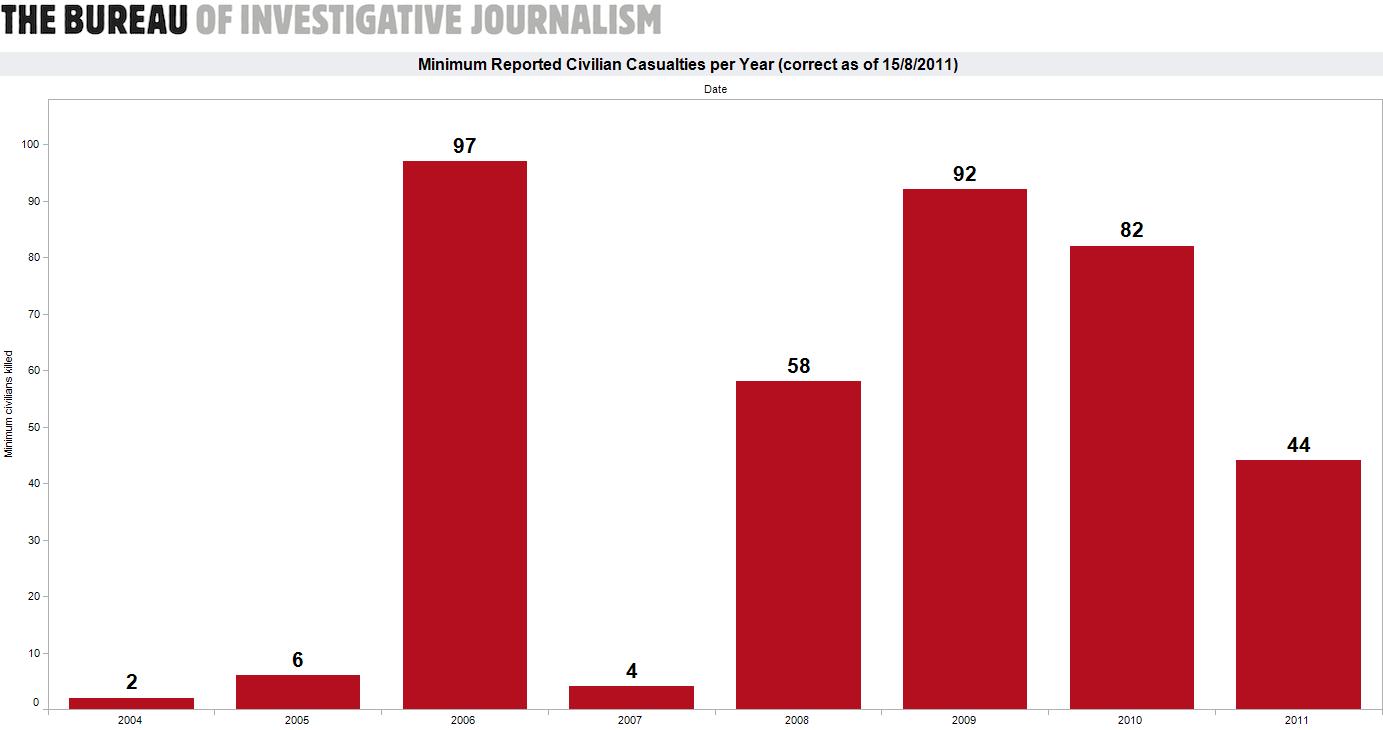

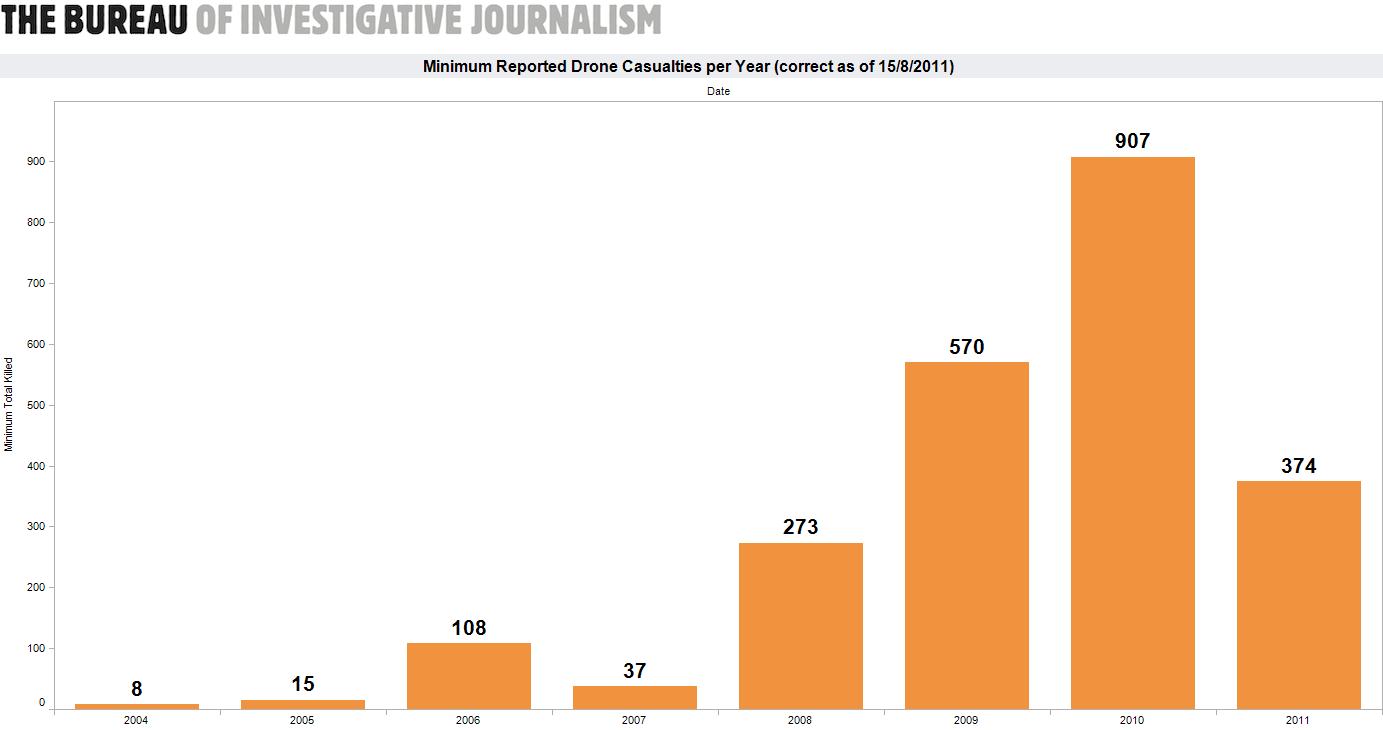

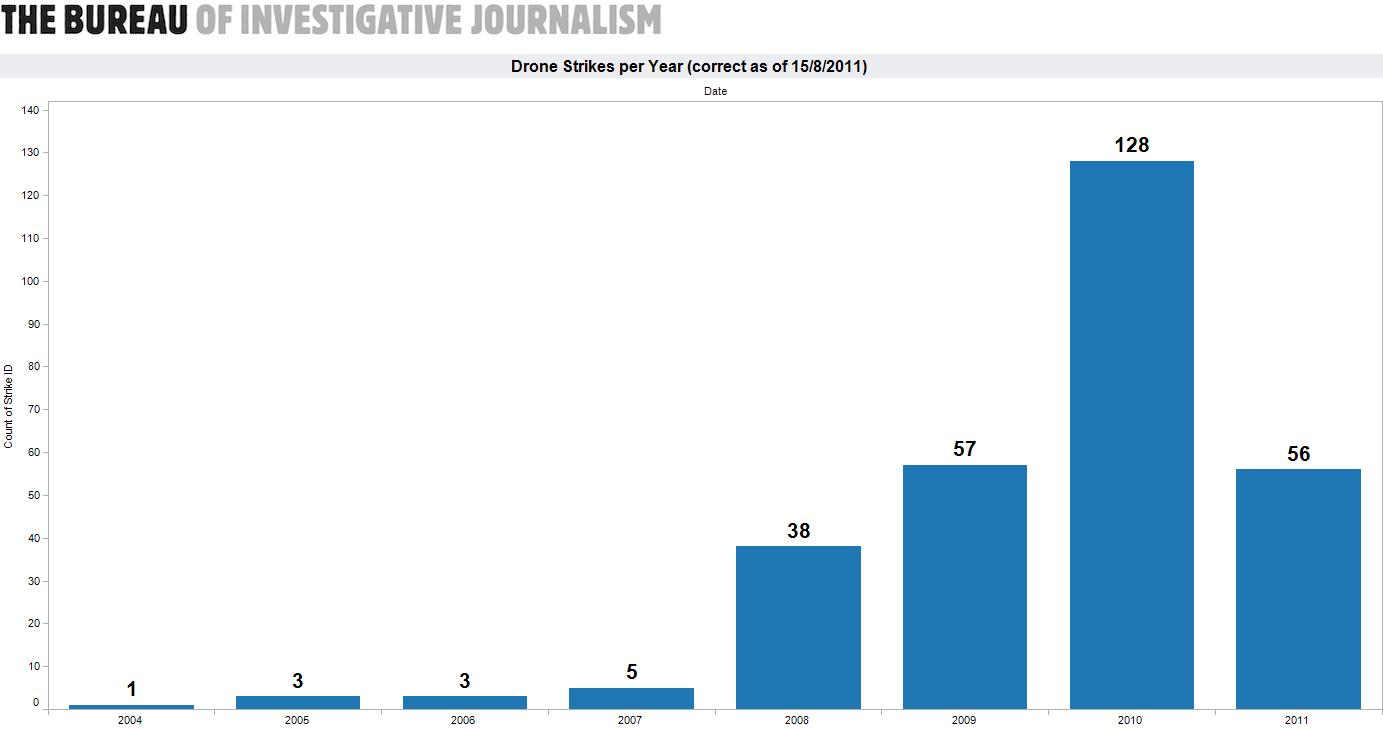

Only a short while thereafter, on 10 August 2011, an extensive new report from the British Bureau of Investigative Journalism came to the conclusion that there had been many more CIA attacks on alleged militant targets, leading to far more deaths than previously reported. It said 291 CIA drone strikes had taken place in Pakistan since 2004, eight percent more than previously reported, and that under President Barack Obama there had been 236 strikes (or one every four days). The Bureau said most of the 2,292 to 2,863 people reported to have died were low-ranking militants, but that only 126 fighters had been named. It also claimed to have credible reports of at least 385 civilians and as many as 775 civilians being killed (168 of which were children).

The study is based on close analysis of credible materials: some 2,000 media reports; witness testimonies; field reports of NGOs and lawyers; secret US government cables; leaked intelligence documents, and relevant accounts by journalists, politicians and former intelligence officers. The result is the clearest public disclosure so far of the CIA’s covert drone war against the militants.

US intelligence officials, meanwhile, are claiming ‘significant problems with the Bureau’s numbers and methodologies.’ The US government’s own internal estimates of those killed in the drone strikes total about 2,050. All but 50 of these are militants, and that no ‘non-combatants’ have died in the past year.

Here is some statistical data from the British Bureau of Investigative Journalism’s study: