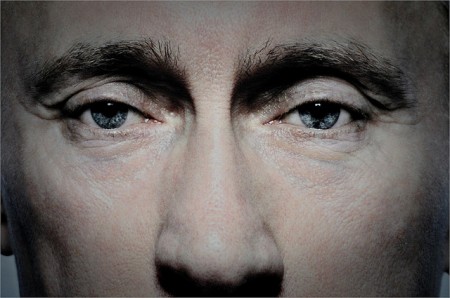

On 24 September, Russian Prime Minister Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin announced his decision to return to the presidency, a post he may now possibly occupy for a further two successive terms until 2024. Unfortunately, his election to the post seems to be a foregone conclusion. In previous polls, opposition candidates, anti-Kremlin parties, and other critics failed to even make it onto the ballot paper. And with Russian state TV having developed into a veritable Putin lovefest, he can expect blanket positive coverage ahead of a lofty coronation.

I am surely not the only one to feel reminded of the dark days of the Soviet period, when the General Secretary’s seat was passed from one frail, tottering character to the next, and political prognostication revolved solely around signs of imminent death – since death was the only thing that could open the door to real reform.

However, on closer examination, it hardly seems fair to compare Putin’s reign with the gerontocracy of the Soviet period, as the Soviets at least had a Politburo. Russia’s current transformation into what political scientists are calling a sultanistic or neo-patrimonial regime is a break from Russian history and the global trend toward democratization. The czars at least drew their legitimacy from their blood and their faith, and the General Secretaries owed their power to their party and their ideology, Putin’s rule, however, is based solely on the man himself.

If there is a blueprint for Putin’s form of government, it is the dictatorships of Central Asia. There is coherence in the autocratic style of Mr Putin, as with his counterparts in Belarus, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan and Azerbaijan. In all those places, political competition is treated like warfare. Political rivals are portrayed as evil-doers and centralized power is accepted as the only way to manage an ever more complex and seemingly overwhelming system.

It is a measure of Russia’s lack of civil society that no one honestly doubts that Putin will win next year’s presidential election. At the same time however, Russia’s population is becoming increasingly more difficult to control. The country is gradually becoming a petro-state, with all the problems such systems spawn: pervasive corruption, sharp income differentiation, a lack of social mobility, a decline in scientific and technological progress, and increased control of the economy by government monopolies.

The cure for the growing systemic and increasingly acute malaise is obvious: ‘modernization’. In the past, both Medvedev and Putin have uttered that word hundreds of times, but have as yet failed to embrace its final implications: impartial courts, honest and competent bureaucracies, a truly uncensored press, free and fair elections, de-monopolization of key sectors of the economy and a reduction of state control.

We have known since 1996 that Russia is no democracy. Yet it is now starting to dawn on us that Russia is not even a “traditional” dictatorship controlled by a party, dynasty, or priesthood. It is a regime ruled by one single man. Yet the challenges posed by rulers who cling to their power are systemic: Touch one part of the vertical of power and the whole fragile structure collapses. The winds of change may be blowing across the Arab world, rolling from Cairo’s Tahrir to Tripoli’s Green Square. Russia, meanwhile, seems to be looking at an endless Putin epoch, an extended period of political stagnation, and a bleak future. I never thought I’d hear myself say this, but maybe it’s time to bring back the Politburo.

Recommended reading

In 2007 Luke Harding arrived in Moscow to take up a new job as a correspondent for the British Guardian newspaper. Within months, mysterious agents from Russia’s Federal Security Service had broken into his flat. He found himself tailed by men in cheap leather jackets, bugged, and even summoned to Lefortovo, the KGB’s notorious prison. The break-in was the beginning of an extraordinary psychological war against the journalist and his family. Mafia State: How one reporter became an enemy of the brutal new Russia is a haunting account of the insidious methods used by a resurgent Kremlin against its so-called “enemies”.