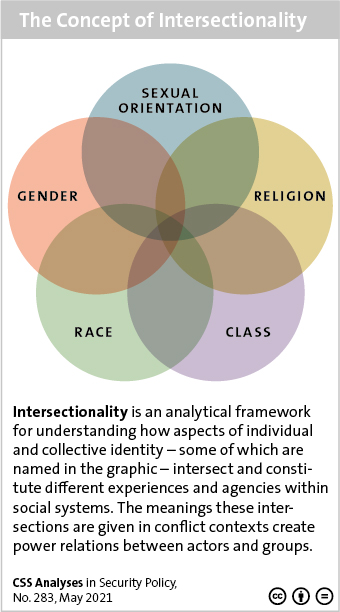

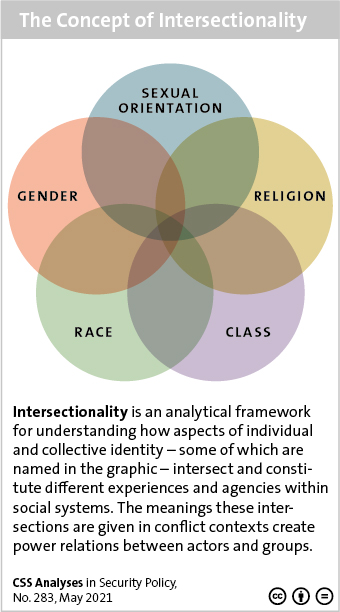

This week’s featured graphic shows the concept of intersectionality. To find out more on religion and gender in conflict, read Cora Alder’s CSS Analyses in Security Policy here.

This week’s featured graphic shows the concept of intersectionality. To find out more on religion and gender in conflict, read Cora Alder’s CSS Analyses in Security Policy here.

This article was originally published by the Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO) on 21 March 2019.

Known as one of the safest and most isolated countries in the world, New Zealand has experienced its darkest day, a terrorist attack perpetrated by a lone gunman against Muslim citizens in Christchurch in two mosques during Friday prayers. For us, in this antipodean part of the world, it is our 9/11 reckoning.

‘This is not us,’ is the resounding response across New Zealand (NZ) since the March 15th attack.

This article is based on a collection of insights published in “Gender in Mediation: An Exercise Handbook for Trainers”, produced by the Center for Security Studies at ETH Zurich in November 2015.

How can conflicts be resolved without one side imposing their view of what is right and good on the other side? This is at the heart of mediation as a method to deal with conflict, and also at the heart of a transformative understanding of gender equality. Both approaches question paternalistic and patriarchic ways of resolving conflict, where a leader decides what is right for others without listening to their views. Rather than seeing gender equality as a question of political correctness and normative necessity, we should explore it as a fundamental shift in how we shape societies and deal with conflict: questioning patriarchy and fostering cooperative decision-making processes.

This article was originally published by USApp – American Politics and Policy, a blog hosted by the London School of Economics and Political Science.

The wars in Afghanistan and Iraq have engendered significant scholarly focus on discourses of war. Consequently, an emerging body of literature is providing critical insights into many facets of war, especially in response to the unprecedented expansion on women’s military participation.

Italy is one of those countries where a lot of wild contradictions regarding gender, misfortune, and economic circumstance can occur simultaneously. Take the word “mignotta,” which is Roman dialect for “whore,” “bitch,” or “slut”—when referring to a woman. Or a gay man. Or a transsexual man. Or, for that matter, simply an untidy woman. But which originally, back in the Middle Ages, was an acronym referring to an abandoned child whose mother was unknown to the local authorities.

Nothing since that time has changed much in Italy, a country where it is still (a) not a good idea to be a woman, if you can possibly avoid it, and (b) a great place to be a woman, but only under special circumstances. Such as if you’re extremely beautiful, very young, and never met former Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi.