Education in developing countries is often a subject of controversy. But it can also be an example of absurdity.

Let’s take the example of technological development in Namibia.

Namibia, with 2 million inhabitants and a $5,000 a year per capita GDP, is one of the richest countries in Africa. It has also been politically stable since it gained independence from South Africa in the 1990s. Natural resources, uranium and diamonds among them, as well as tourism guarantee the country a comfortable income.

But the country is also benefiting from international aid.

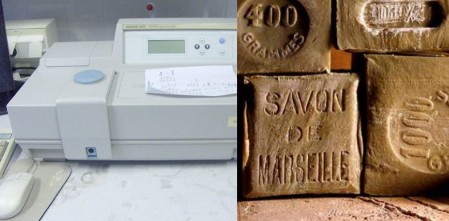

The Polytechnic of Namibia, the leading technical university of the country, benefits from aid it gains from international foundations. Recently they received 30 spectrophotometers, for example. This tool is used to study the electromagnetic spectra of an object. A foundation answered to a request by the Polytechnic that wanted these tools to compete technologically with the best universities in the world. With one spectrophotometer costing approximately $5,000, the donation amounted to $150,000.

This is a lot for a university where some professors don’t earn as much as one spectrophotometer costs during one year. And the ‘funny’ part of the story is that these tools are not used more than a few times a year.

While every chemistry students of the Polytechnic now has his or her own spectrometer, the university still lacks some basic supplies. It doesn’t have soap, for example, which is crucial when analyzing bacteria or working with chemistry products. It should be used daily in a laboratory. Last month, one international professor that was working there, had to ask the kitchen if she could borrow the soap to show the students how to clean their hands before analyzing bacteria with a microscope.

But what does this example tell us?