ANKARA – Last week, Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan intensified his government’s response to the corruption investigations that have been roiling the country since December, restructuring the leadership of the judiciary and police. But it would be a mistake to view this as a fight between the executive and the judiciary, or as an attempt to cover up charges that have led to the resignation of three ministers. What is at issue is the law-enforcement authorities’ independence and impartiality. Indeed, amid charges of fabricated evidence, Erdoğan now says that he is not opposed to retrials for senior military officers convicted of plotting to overthrow his government.

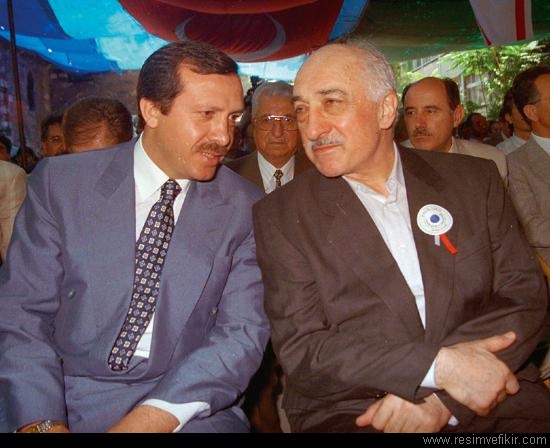

The recent developments reflect the widening rift between Erdoğan’s government and the Gülen movement, led by Fethullah Gülen, a self-exiled Islamic preacher currently residing near Philadelphia. The Gülen movement was an important backer of the governing Justice and Development Party (AKP) and its efforts to establish civilian control over the military during the AKP’s first two terms in office. Now, however, the movement appears to have been plotting a coup of its own.

Many members of the judiciary and the police force associated with the wave of corruption charges brought against government officials, businessmen, and politicians’ family members are connected with the Gülen movement. What started out as an investigation into alleged graft soon became an opposition-supported smear campaign.

Turkey’s current struggles raise important questions about the appropriate relationship between bureaucrats and elected officials in a pluralist democracy. Answering them will require a debate that transcends issues like the separation of powers and judicial independence and elucidates the appropriate relationship between politics and religion. For that, understanding the historical context of the current crisis is crucial.

When Turkey became a democracy in 1950, the previous system’s secular Kemalist elites attempted to harness the power of the military and the bureaucracy to control the elected government. In fact, the Turkish military, with the judiciary’s support, explicitly intervened in the civilian government’s functioning in 1960, 1971, 1980, and 1997, each time in the name of protecting secularism.

In response, various religious groups, including the Gülen movement, encouraged their followers to take positions in the bureaucracy and the military. In the 1990’s, military-backed secularist governments struck back, attempting to purge religious bureaucrats and military leaders: those who did not consume alcohol, or whose family members wore headscarves, were immediately suspected.

With the normalization of Turkish democracy following the AKP’s victory in 2002, restrictions on the recruitment, employment, and promotion of religious citizens in the upper echelons of the bureaucracy were eliminated – a process that especially benefited members of the Gülen movement, with its extensive education, media, and business networks. Gülen followers – who claimed to support liberal democracy and the tolerant, modern form of Islam embraced by the AKP – seemed like natural allies of Erdoğan’s government.

For a decade, Gülen-connected companies played a widely acknowledged – and appreciated – role in Turkey’s economic growth and development, while Gülen-movement schools trained students to pursue public-service jobs. As long as bureaucrats were recruited and promoted based on merit, the AKP had no problem accepting the over-representation of Gülen followers in certain branches of government.

This acceptance was rooted in the belief that Gülen members would adhere to the fundamental requirement in a pluralist democracy that bureaucrats – whether Muslims in Turkey, Mormons in the United States, or Buddhists in Japan – do not allow their religious convictions to trump their commitment to public service and the rule of law. What the government did not imagine was that a new vision of bureaucratic tutelage over the civilian government would emerge.

Although Gülen followers have disagreed with several of the government’s policies, they largely backed the AKP in the last three elections. What drove them to reject the party completely was a policy debate on restructuring “cram schools” – expensive private institutions that prepare high-school seniors for their university entrance examinations.

The Gülen movement operates at least one-quarter of these schools, which form a key component of the movement’s multi-billion-dollar education network and help it recruit new members. The movement’s members thus viewed the debate over cram schools as a direct challenge to their influence.

But their reaction was disproportionate – not least because the government’s plans were not finalized. Moreover, the proposal had nothing to do with the Gülen movement; the government was responding to citizens’ complaints about having to pay extravagant fees to prepare their children for free public universities. And the Gülen movement was not exactly caught off-guard; cram-school representatives had been engaged in a dialogue with education-ministry officials for some time.

As in any democracy, public criticism of Turkey’s government policies is normal and healthy. But attempts by Gülen-aligned members of the judiciary and the police force to blackmail, threaten, and illegally bargain with the government are unacceptable.

Now, it is up to the courts to discern the truth about corruption among Turkey’s so-called “public servants.” But all of the signs point to a coordinated political crusade by Gülen followers, including the chief prosecutors involved in the recent corruption cases and the pro-Gülen media that have steadfastly defended the prosecutors’ impartiality (despite the many irregularities – such as extensive unauthorized wiretaps – that have come to light). Moreover, a coordinated group within the judiciary is suspected of planting evidence – allegations that have led to the calls for military personnel to be retried.

To be sure, this does not mean that there were no coup attempts by members of the military in the past or cases of corruption by politicians and bureaucrats. The point is that Turkey needs judicial reforms that eliminate the possibility of organized cliques manipulating their constitutional powers to advance their own narrow goals.

This is a red line for any pluralist democracy. Individual citizens should be free to live according to their beliefs; but an unaccountable theological vision must not be allowed to shape their behavior as civil servants and bureaucrats.

More generally, the debate about the Gülen movement should serve as an opportunity to clarify the relationship between religion and politics, while reminding the Turkish public – and Muslim-majority countries throughout the region – of the core democratic values that have enabled Turkey to develop and thrive.

Copyright Project Syndicate

Ertan Aydin is a senior adviser to Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan.

For additional reading on this topic please see:

Überdehnt sich die Bewegung von Fethullah Gülen?

Turkey: Has the AKP Ended Its Winning Streak?

Turkey’s “Super Election Year” 2014: Winner Still Takes All?

For more information on issues and events that shape our world please visit the ISN’s Weekly Dossiers and Security Watch.