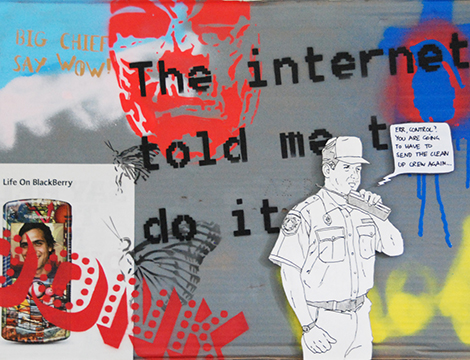

Image courtesy of @mod_russia on Twitter.

What does the reported first battle use of a hypersonic missile mean for the dynamic of Putin’s war in Ukraine? Open-source intelligence sources suggest that the Russian Kinzhal is a propaganda weapon.

On early Saturday March 19, the Russian Ministry of Defence released a video claiming that Russian forces fired a Kinzhal (“dagger” in Russian) missile against a military ammunitions warehouse close to Ukraine’s borders with Romania and Hungary. If this strike really did occur, it would be the first known battle use of a hypersonic weapon. However, the expert community has already pointed to several inconsistences in this Russian story. Furthermore, the use of Kinzhal would not alter the military balance in Russia’s favour. The second alleged launch of Kinzhal, which was supposed to have hit a fuel depot in Kostiantynivka near Mykolaiv on Sunday, was simply announced by defense ministry spokesman at a press conference.