This article was originally published by ISS Africa on 12 January 2016.

Africa starts the New Year with many burning issues that escalated in 2015 and need urgent action. The crisis in Burundi, where grave human rights violations are continuing, and the war in South Sudan are the two most pressing among these.

This year will also see a number of important elections taking place in Africa. Uganda’s presidential polls are being held next month, and those scheduled for the Democratic Republic of Congo later this year will also be top of mind for most Africa watchers.

It will also be a very challenging year for Nigeria’s President Muhammadu Buhari, who will now have to make good on his 2015 election promises.

This includes effectively dealing with terror group Boko Haram and bringing back the kidnapped Chibok girls. Africa’s most populous nation will also look to him to continue the fight against corruption and boost economic development, despite the slump in the oil price.

But what are we missing, beyond the big newsmakers?

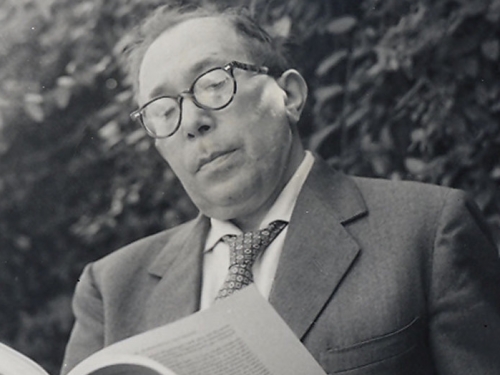

In 2016, we should watch for surprises from unexpected quarters. One of these might be from Zimbabwe. President Robert Mugabe, who turns 92 next month, is not immortal – even if his supporters vow to push him onto the stage in a wheelchair to celebrate his victory at the next party elections in 2019.