This article was published by VoxEU.org on 1 March 2017.

The Scramble for Africa has contributed to economic, social, and political underdevelopment by spurring ethnic-tainted civil conflict and discrimination and by shaping the ethnic composition, size, shape and landlocked status of the newly independent states. This column, taken from a recent VoxEU eBook, summarises the key findings of studies that use high-resolution geo-referenced data and econometric methods to estimate the long-lasting impact of the various aspects of the Scramble for Africa.

Editor’s note: This column first appeared as a chapter in the Vox eBook, The Long Economic and Political Shadow of History, Volume 2, available to download here.

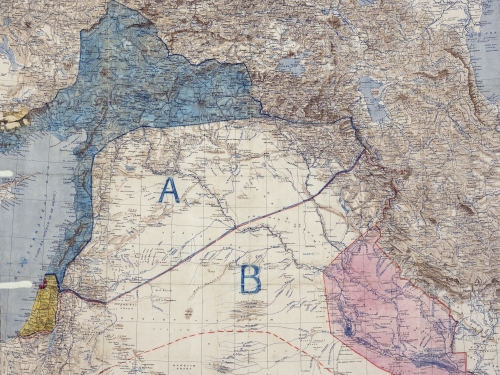

When economists debate the long-lasting legacies of colonisation, the discussion usually revolves around the establishment of those ‘extractive’ colonial institutions that outlasted independence (e.g. Acemoglu et al. 2001), the underinvestment in infrastructure (e.g. Jedwab and Moradi 2016), the identity of colonial power (e.g. La Porta et al. 2008) and the coloniser’s influence on early human capital (Easterly and Levine 2016).1 Following the influential work of Nunn (2008), recent works have explored the deleterious long-lasting consequences of Africa’s slave trades (see Nunn 2016, for an overview). Yet, between the slave-trade period (1400-1800) and the arrival of the colonisers at the end of the 19th century, the Scramble for Africa stands out as a watershed event in the continent’s history. The partitioning of Africa by Europeans starts, roughly, in the 1860s and is completed by the early 1900s. The colonial powers signed hundreds of treaties, which involved drawing on maps the boundaries of colonies, protectorates, and ‘free-trade’ areas of a largely unexplored and mysterious continent (see Wesseling 1996 for a thorough discussion).2 In this context it is perhaps not surprising that many influential scholars of the African historiography (e.g. Asiwaju 1985, Wesseling 1996, Herbst 2000) and a plethora of case studies suggest that the most consequential aspect of European involvement in Africa was not colonisation per se, but the erratic border designation that took place in European capitals in the late 19th century.