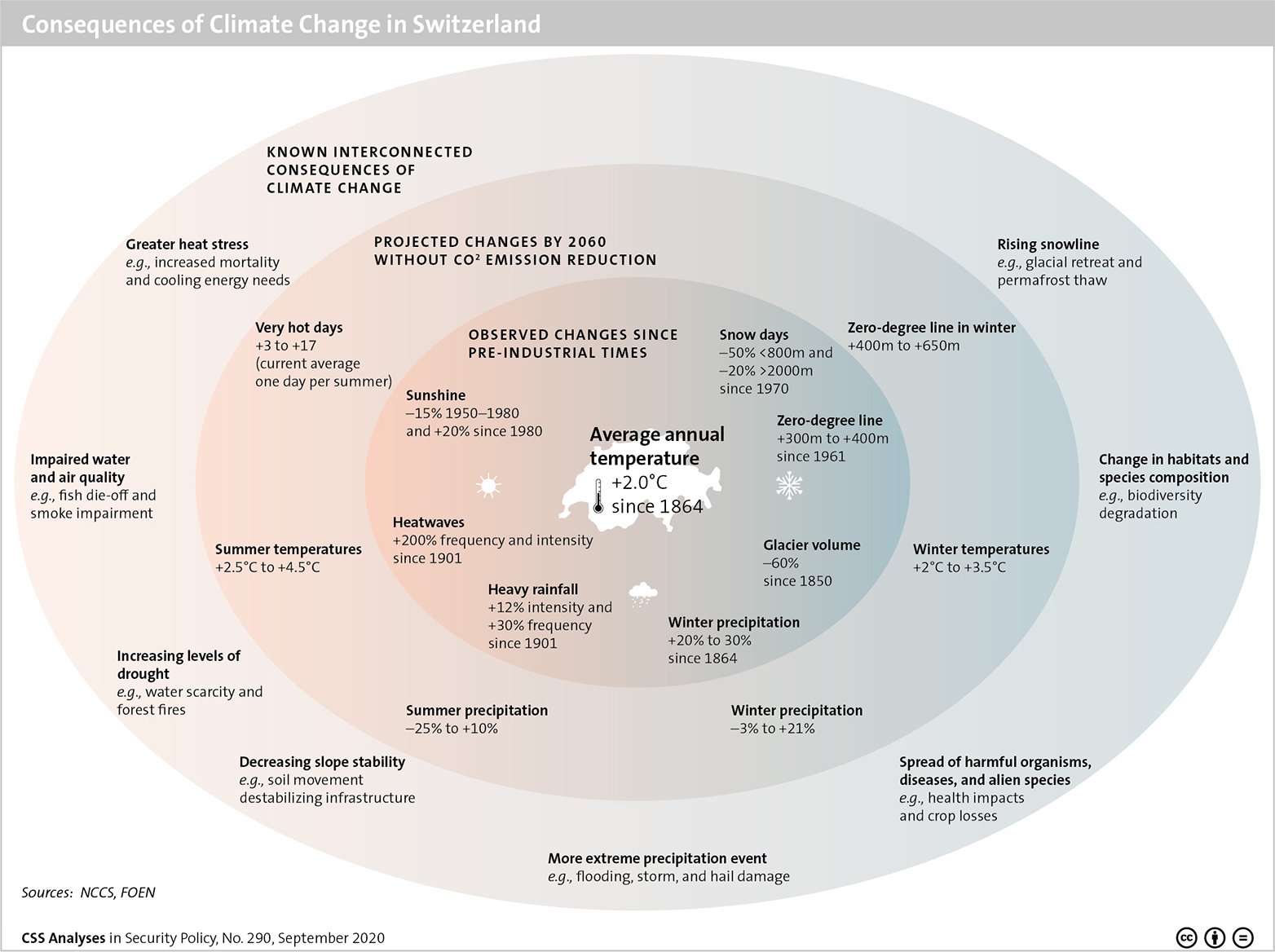

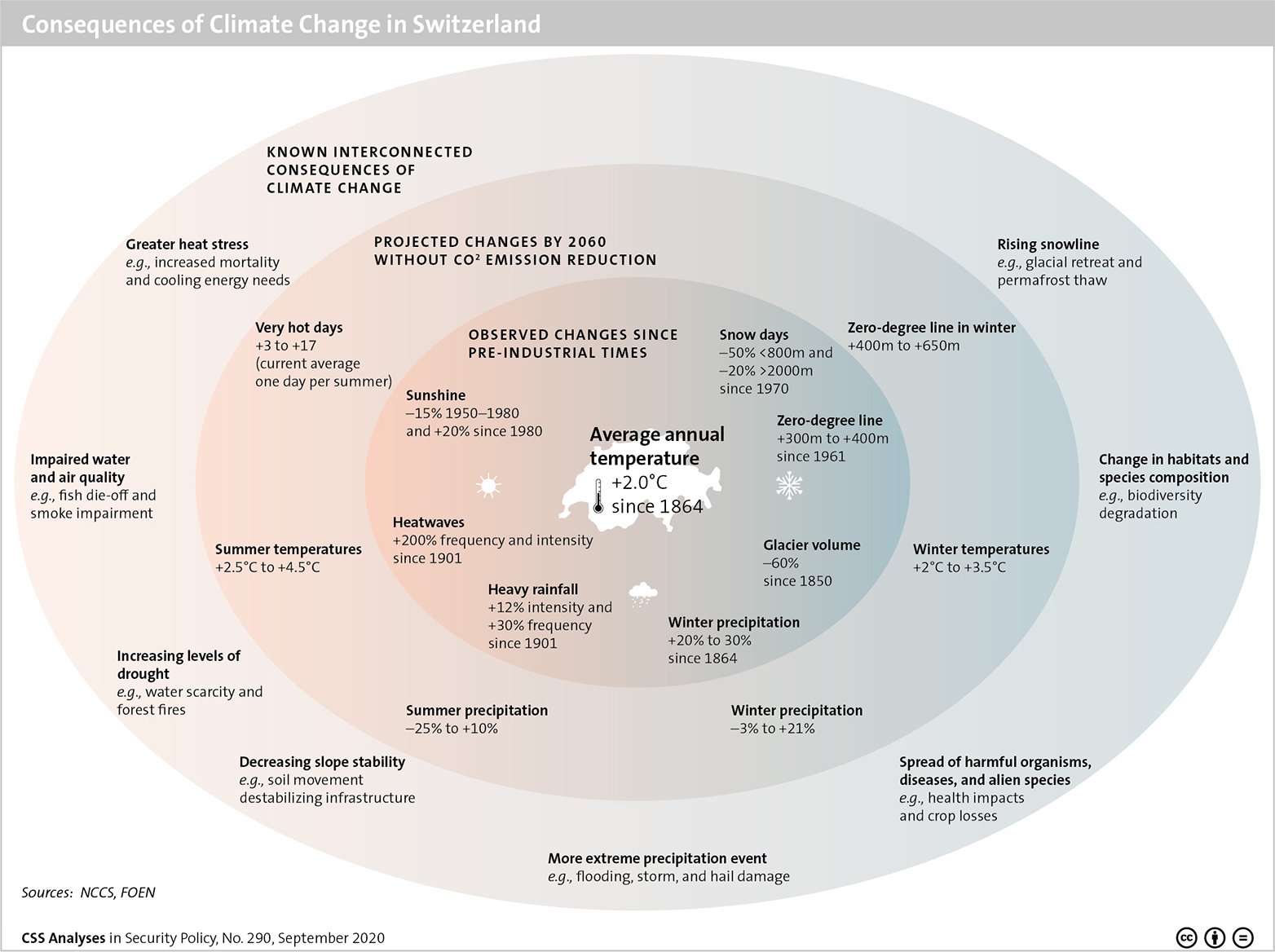

This week’s featured graphic illustrates the consequences of climate change in Switzerland. For more on Climate Change in the Swiss Alps, read Christine Eriksen and Andrin Hauri’s CSS Analysis in Security Policy here.

This week’s featured graphic illustrates the consequences of climate change in Switzerland. For more on Climate Change in the Swiss Alps, read Christine Eriksen and Andrin Hauri’s CSS Analysis in Security Policy here.

This article was originally published by the Danish Institute for International Studies on 1 December, 2015.

In Vietnam, the rainy and dry seasons are increasingly unpredictable. Such climate changes have a greater impact in Vietnam than, for example, in Denmark. Many in Vietnam live off the production of rice and other crops, and their livelihoods are dependent on fixed seasons.

Local governments are actively trying to address such changes and resulting challenges with more accurate seasonal forecasts, different crop varieties and more effective water management. However, they are often limited by shortage of funds. This is just one of many examples illustrating both the need for securing adaptation in poorer countries and local governments’ key role in implementing adaptation.

This article was originally published on 6 April 2015 by New Security Beat, the blog of the Environmental Change and Security Program (ECSP) at the Wilson Center.

Expectations for the upcoming UN climate change summit in Paris are higher than they’ve been in years. Experts expect it will be the best chance to achieve a binding, universal agreement to limit carbon emissions. But the conference is still not getting the attention it deserves from policymakers and the public, given the stakes – and not just for the environment but for the international system writ large, said Nick Mabey, founding director and chief executive of the UK-based environmental NGO E3G at the Wilson Center on February 12.

For those (still) interested in climate change issues, two things are happening next week that are worth to ponder:

First, Global Warming is turning 35! As announced on the blog of the RealClimate website, the term “global warming” was used for the first time in an article by Wally Broecker in the journal Science on 8 August 1975. Happy Anniversary!

Second, a UN Climate Change Confererence will be held next week (2 – 6 August 2010) in Bonn, discussing possible contributions by both industrialized and developing countries to reduce emissions. Further issues to be discussed include how to adapt to climate changes, slow down deforestation and develop new technologies – and how all these measures can be financed. The conference is intended as a further preparation for the sixth meeting of the Parties to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), which will take place in Cancun, Mexico, in November and December 2010.

Yet the global optimism prior to last year’s Copenhagen Summit, when there was so much hope that a newly elected US president who promised change and truly seemed to care about the environment would finally lead the world into a new, environmentally more responsible era, has all but vanished.

Forget the complexity of global warming and the diffuse threat posed by global terrorism. Back in the day, problems faced by the international community seemed so much more manageable. During the Cold War, we knew who the bad guys were and where the threats came from. Environmental degradation became an important issue in the 1980s, but the problems we faced still seemed pretty straightforward: to halt de-forestation and soil erosion, we have to stop cutting trees without replacing them; to prevent the whole-sale extinction of endangered species, we have to stop hunting them.

Relatively straightforward also was the first man-made atmospheric problem humankind faced back in the ’80s: the ozone hole.

The culprit, as scientists were able to convincingly show, was a single chemical substance: the ozone-depleting hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs), widely used as coolants in refrigerators, air conditioners and aerosol cans.

The international community got together in Montreal and agreed to phase out the use of this ozone-depleting substance. The result was the Montreal Protocol, which entered into force in 1987 and was touted by former UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan as ” perhaps the single most successful international agreement to date.”

Since January 1 of this year, developed states are bound by the treaty to cut HCFC consumption and production by 75 percent. The ozone hole is now slowly on the mend and scientists expect the hole to close within 50 to 100 years.

But as all our problems seem to be getting more and more complex in the 21st century, so does the good old ozone hole saga.

According to a recent piece in the New Scientist, the ozone hole over Antarctica is slowing down the warming of Antarctica (and thus the rising of sea levels). This is so because the thinning of the ozone layer is strengthening circumpolar winds that have a cooling effect on Antarctica. Once the ozone hole is closed up, the theory goes, it will trap more hot air and accelerate the melting of Antarctic glaciers.

It almost sounds as if global warming has turned the environmental success story of the 1980s into a no-win.

Or perhaps not? A scientist at Canada’s University of Waterloo, Professor Qin-Bin-Lu, now argues that the straightforward ban of HCFC in fact was more of a silver bullet to man-made atmospheric changes than we could have possibly imagined back in the ’80s.

Indeed, he argues that HCFC, and not CO2, is to blame for global warming all along. His satellite and balloon measurements show that HCFC is tens of thousands of times more potent as a greenhouse gas than CO2 on a molecule per molecule basis. Hence, Lu expects the global phase-out of HCFCs to eventually allow global temperatures to revert back to pre-HCFC levels.

It is an interesting theory, but to me it simply sounds too good to be true. As a member of generation X, I’m used to problems being more complex than that, and I have been taught that there simply is no silver bullet or straightforward solution to the complex global threats out there.

Besides, cutting our CO2 emissions and not burning down our forests still seem like pretty good ideas to me.