This article was originally published by the Lowy Institute for International Policy’s The Interpreter on 1 June 2016.

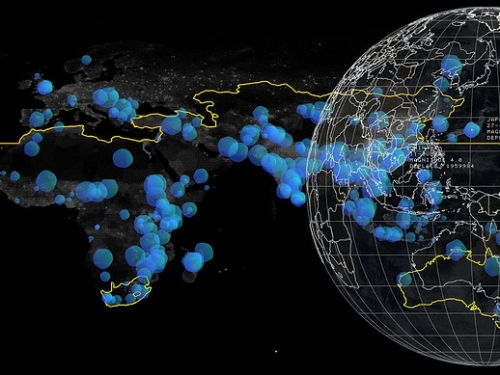

Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, the global political and economic architecture has been undergirded largely by one superpower, which set the stage for an unprecedented period of globalisation managed through multilateral institutions and actors. Now that unipolar moment is giving way to an era of diffused powers, with countries like the US, China and Russia each bearing considerable disruptive capacities, and each struggling to stitch together new norms and rules for these rapidly changing times.

This phase, the beginning of which was marked by the Global Financial Crisis of 2008 and characterised by America’s two bruising wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, has seen a vacuum emerge. Many are seeking to fill it, most determinedly China, but with a push back from countries such as Japan and India. Separately, ISIS and radical energies in the Middle East also seek to grab new space. Russia has chosen this very moment to signal its ability to muddy the Eurasian fields and intervene in the Middle East. The fact is, there is not enough room to accommodate all of these ambitions.

A median will have to be arrived at, but who will sacrifice what?