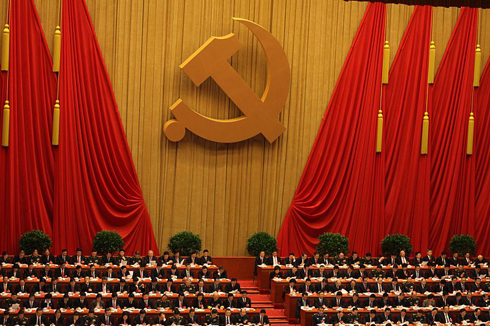

WASHINGTON, DC – Xi Jinping, China’s newly anointed president, made his first visit to the United States in May 1980. He was a 27-year-old junior officer accompanying Geng Biao, then a vice premier and China’s leading military official. Geng had been my host the previous January, when I was the first US defense secretary to visit China, acting as an interlocutor for President Jimmy Carter’s administration.

Americans had little reason to notice Xi back then, but his superiors clearly saw his potential. In the ensuing 32 years, Xi’s stature rose, along with China’s economic and military strength. His cohort’s ascent to the summit of power marks the retirement of the last generation of leaders designated by Deng Xiaoping (though they retain influence).