This week’s featured graphic maps the states of the Western Balkans. To find out about the rearmament in the Western Balkans, read Andrej Marković and Jeronim Perović’s CSS Analysis in Security Policy here.

This week’s featured graphic maps the states of the Western Balkans. To find out about the rearmament in the Western Balkans, read Andrej Marković and Jeronim Perović’s CSS Analysis in Security Policy here.

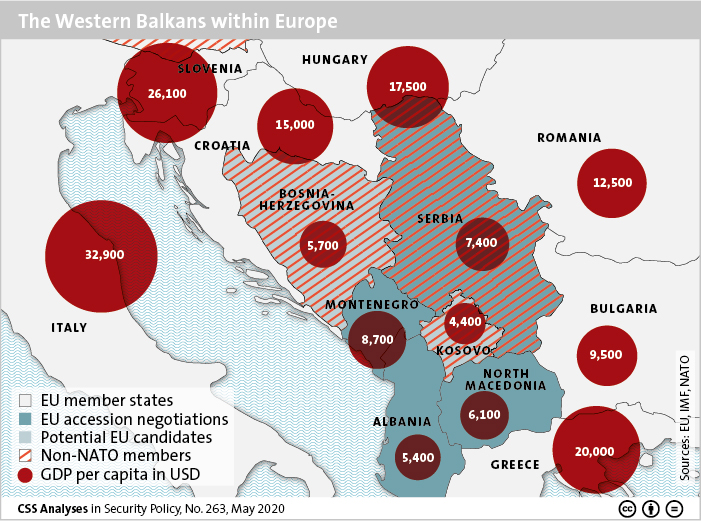

This graphic maps the Western Balkans in Europe focusing on their GDP. With the exceptions of Croatia and Slovenia, the Western Balkans are unable to achieve growth rates that enable it to catch up with EU averages. The average GDP per capita for the six countries is half that of Central European countries and only one quarter of that of Western Europe.

For insights on the Western Balkans between the EU, NATO, Russia & China, read more of Henrik Larsen’s CSS Analyses in Security Policy here.

This article was originally published by European Council on Foreign Relations on 13 October 2017.

It is high time for the EU to move beyond ‘stabilocracy’ and stand up to ethnic nationalist kleptocrat political leaders.

The Balkans are not as exciting as they once were. The large-scale violence that made the region a central concern of European policy in the 1990s is no longer a feature of Balkan politics.

That’s progress, of course. But the absence of violence does not mean an absence of problems. Persistent economic weakness, growing public frustration with leaders, and renewed ethnic tensions have created a volatile mix beneath the surface calm. As Europe’s attention to these issues wavered, outside actors – most notably Russia, but also Turkey and China, began to assert themselves. If the European Union wants to maintain stability and influence in its own troubled backyard, it will need to re-engage with the Balkans.

This article was originally published by International Crisis Group on 28 April 2017.

The Balkans was best known for minority problems. Today, the most bitter conflicts are between parties that appeal to majority ethnic communities. As recent turbulence in Macedonia shows, Eastern Europe could face new dangers if majority populism ends the current stigma against separatism for oppressed small groups.

The trouble in the Balkans today is not Russian meddling, though there is some of that, but a special case of the malaise afflicting Eastern Europe: unchecked executive power, erosion of the rule of law, xenophobia directed at neighbours and migrants and pervasive economic insecurity. The pattern varies from country to country but is palpable from Szczecin on the Baltic to Istanbul on the Bosporus. The countries of the Western Balkans – Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, Macedonia, Montenegro, and Serbia – have long tended to follow patterns set by their larger, more powerful neighbours. They are doing it again.

The ability of the European Union (EU) to fix problems in the Balkans is hamstrung when the same troubles persist within its own borders, sometimes in more acute form. Take erosion of democratic norms: Hungary over the past decade has slid from 2.14 to 3.54 on Freedom House’s “Nations in Transit” democracy score (lower is better). Poland’s decline is more recent but equally steep. Croatia is also backsliding. Almost all the Western Balkan states are declining, too, but more slowly.

This article was originally published by the European Council on Foreign Relations on 5 August, 2015.

No business as usual in the Western Balkans

The Western Balkans remain Europe’s unfinished business, not only for the continuing stalemate in Bosnia or tensions in Macedonia and Northern Kosovo, but also because broader geopolitical developments shaping the EU’s neighbourhood are materialising in this region too – and in ways that could be detrimental to European interests.

Tensions and perception of a stalemate in the Balkans are enhanced by “the five year freeze”, while emerging forms of rule are at odds with the EU’s founding tenets and the integration narrative. Indeed, the same competition of models, that we see in other parts of Europe, which pits more or less pluralist democracies against populists or illiberal democracies in the mould of Viktor Orban or even “Putinism”, is played out in the Western Balkans too, with uncertain outcomes for this fragile region. Ironically, in the very part of the world where the EU is in the lead and where its influence, through its transformative power, should be at its most potent, local experts concur that the EU is no longer the leading actor and that its leverage has decreased.