Mediation Perspectives is a periodic blog entry provided by the CSS’ Mediation Support Team and occasional guest authors. Each entry is designed to highlight the utility of mediation approaches in dealing with violent political conflicts.

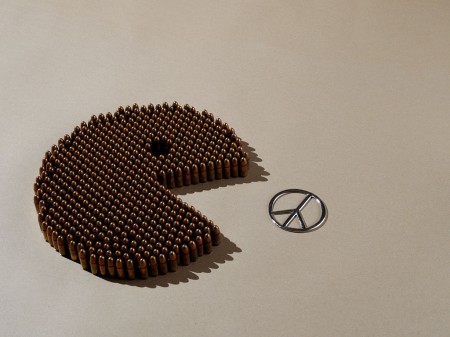

Most armed conflicts since the end of the Cold War have been civil wars. In contrast to wars between states, civil wars last longer – on average for seven to ten years – and usually end in some kind of settlement. Such settlements can result in mere ceasefires or, in more ideal cases, power-sharing agreements and genuine attempts to deal with the root causes of conflict. Yet one in two civil war settlements fail and violence reoccurs. Today’s blog provides one explanation for why this rate is so staggeringly high – the ‘spoiler’ role played by governments.

In most cases, peace deals in civil wars are signed when warring parties are weak, particularly the government. Military stalemate, exhaustion, and external pressure may encourage belligerents to settle at the negotiating table. Under such circumstances, a settlement is likely to be a compromise that still threatens some actors’ power, worldview and interests. As a result, they may try to undermine or ‘spoil’ the agreement in a way that allows them to reap the benefits they consider favorable, while not paying its designated price. The benefits may include retaining state power, gaining international or domestic recognition for committing to peace, continued exploitation of resources, and maintaining patronage networks, among many others.

Given these benefits, the underlying reasons why peace deals aren’t complied with are thus plentiful. Yet the media, as well as academia and its ‘spoiler theory’, all too often focus on the violent breaches of a peace and attribute blame to the rebel group. But since being a ‘spoiler’ works both ways, we’re left with a glaring question: How do governments impede or violate peace agreements and what non-violent means do they employ towards that end?

A government’s advantages

Governments enjoy several advantages over non-state groups when it comes to both negotiating and implementing peace deals.

The first involves sovereignty and legitimacy. Basically, the international community tends to see an incumbent government as the legitimate sovereign. Rebel groups are by definition considered to be both illegal and illegitimate by large parts of the international state system. Negotiating with rebels is thus seen as exceptional, while dealing with governments is perceived to be everyday diplomacy. Even on the domestic front, forms of quasi-democratic legitimacy are easier to gain as a government than as a rebel group.

The second advantage is linked to funding and its sophistication. A government’s sources of financing are likely to be ampler and more diverse than a rebel group’s, primarily through its access to international trade and financial networks. Indeed, since government ministries perform more functions and have greater expertise than the proto-institutions of rebel groups, it’s typically easier for them to rearm and finance the state. Also, having official representations abroad and in international organizations translates into more professional and better-funded negotiation delegations.

The third advantage of governments over non-state actors centers on controlling information. Dominating the narrative and influencing the flow of information is crucial, particularly in messy civil wars where little independently verified information is available. The government, at least initially, is considered to be a more credible and trustworthy source of information than a rebel group. Even in the long run, the government has more resources and means to push its conflict narrative forward, which then enables it to euphemize its own spoiling behavior and to blame others for failing to maintain the peace.

Machiavelli for President: How to undermine peace non-violently

By enjoying the above advantages, the government or parts of the state apparatus can undermine a peace process in a variety of ways. Many of them are non-violent and therefore don’t garner the attention they deserve. They include:

· Idleness: Stalling or delaying the peace process is the simplest spoiling strategy. Procedural obstacles can slow negotiations or their implementation. Elections, in turn, can be postponed or manipulated.

· Bad press: Given the resources it has available, a government can delegitimize its opponents more easily through its own news outlets, as well as influence others.

· Democracy, if convenient: The government can call for a referendum to kill the deal if it expects a sufficient share of the population to reject the proposal. Requiring a qualified majority, or resorting to intimidation and fraud, can further assure that the peace agreement does not pass.

· Relabeling: Being the assumed legal sovereign, the government can misrepresent a military campaign as a ‘police operation’, downsize the size of its military while swelling the ranks of its paramilitary ‘police’, or veto or arrest the opponent’s representatives. By relabeling things in this way, the government may not violate the legal terms of an agreement but it can certainly undermine its spirit.

· Divide and conquer: A government can funnel resources or grant concessions or state services in such a way that it strengthens a specific wing of a rebel group, or it can buy off factions or leaders outright.

· My enemy’s enemy: A government can weaken its main opponent by allying with a rebel group’s enemy, or fostering the fortunes of its smaller competitor. The Sudanese government, for example, has employed this tactic in both South Sudan and Darfur for decades – sometimes with long-term consequences.

If you’re interested in a case study that features many of the above tactics, then look no further than the conflict between the FARC and the Colombian government in the 1980s. At the time, a ceasefire negotiated by a committed president soon collapsed when the army undertook ‘police operations’ against the FARC, which prompted the group to retaliate. The Colombian Parliament then stalled the implementation of large parts of the agreement, while government-paid right-wing militias annihilated the FARC’s new political wing, the Unión Patriótica, by killing 3,000 of its MPs, members and supporters. (For a brief description of the conflict, see here.) This is not to say that significant parts of the government should be solely blamed for the failure of the peace process at the time. Their obstructionist tactics, however, did sabotage the quest for peace until very recently.

Lessons learned

So, what can we learn from the above discussion? First, we need to remember that although simple narratives often put the blame for failed peace processes on rebels, governments have many ways to erode a peace agreement without necessarily risking the same public outcry that bombings and shootings inevitably do. Non-violent breaches of an agreement should therefore be scrutinized as closely as violent ones, especially since they may result in crucial power imbalances, the erosion of trust, and the re-emergence of full-scale war. Consequently, constant and unbiased monitoring beyond observing military incidents is crucially important, as is ensuring that agreements contain implementation mechanisms that minimize belligerents’ room for spoiling behaviors.

Second, it’s important to remember that mediation in civil conflicts can only work if there’s a genuine commitment to embrace the negotiation process and the peace agreement that follows in its wake, including its implementation. Otherwise the agreement will merely be a scrap of paper or, worse, serve as a fig leaf for spoiling behaviors. To assess whether a compromise could be reached, the differing worldviews and material interests of different parties, and of factions within parties, need to be accounted for. The more convinced belligerents are that an agreement offers more benefits than they could achieve through continued violence, the less likely they are to try and spoil it. Joint trust building, for example through Confidence Building Measures, can help create an environment where genuine peace talks can take place, while at the same time reduce the risk of escalatory cycles.

Finally, governments require special attention, given the advantages and protection offered by their alleged legitimacy and the traditional norm of external non-interference. Ideally, international or regional organizations such as the UN or AU should reconsider their state bias. Whether a government succeeds in undermining a peace agreement depends to some degree on the level of tolerance extended to it by the international community. The latter’s mediation efforts in civil wars must therefore straddle a fine line: International actors need to exercise influence and leverage, be consistent and sometimes call a spade a spade, but they also must avoid becoming too intrusive and thereby risk losing the consent they need for a peace agreement that lasts.

Benno Zogg works as a research assistant at the Center for Security Studies. He obtained a Master’s degree with distinction in Conflict, Security and Development from King’s College London with the dissertation this article is based on, entitled “Spoiler Alert – An Analysis of Governments Undermining Peace Processes“.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit ISN Security Watch or browse our resources.