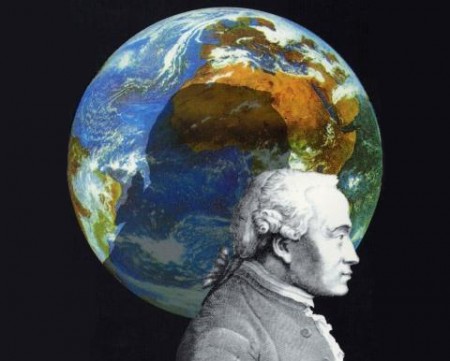

In another foray into the realm of theory, to complement our Editorial Plan’s discussion of international norms and laws, we turn to a giant in the history of thought, the German philosopher Immanuel Kant. Though known primarily as a moral philosopher, Kant also wrote on topics germane to international relations and international political theory, in works such as Idea for a Universal History (1784) and Perpetual Peace (1795). Today we look briefly at what Kant had to say about international law, through Amanda Perreau-Sassine’s interpretive essay in The Philosophy of International Law, edited by Samantha Besson and John Tasioulas. Kant’s view of international law, it turns out, has important implications for contemporary discussions.