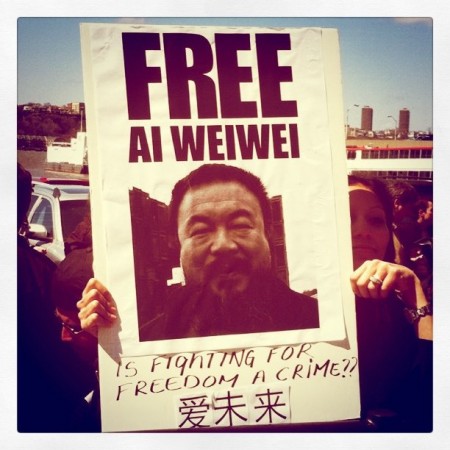

China’s Ai Weiwei has recently been removed from the creative scene. Absent and yet present, he is an artist whose work has become renowned all over the world in recent years.

Special attention was given to Ai particularly because of his creative criticism and involvement in social and political questions concerning China. In 2007, for example, at the Documenta 12, one of Europe’s biggest art fairs, Ai provoked his public by inviting along 1001 Chinese compatriots. His statement was simple yet powerful. Ai’s experiment raised awareness about how China is booming, but at the same time, about how it remains separated from the West.

Despite the regime’s restrictions, new art in China has found diverse channels of expression in the years since 1989, ranging from direct criticism of Western consumption, to mocking stereotypes of Maoist propaganda or to addressing the weaknesses of the communist regime. Ai Weiwei belongs to the latter group of creatives. He is one of China’s best-known artists and at the same time one of China’s most despised dissidents.

Ai’s arrest at the beginning of April 2011 was met with consternation by the international public. Yet the most recent wave of repression affected not only Ai, but the entire Songzhuang art district, in the eastern suburbs of Beijing. This community of artists had elected a suggestive name for their latest exhibition: Sensitive Zone. The exhibition was in itself a provocation, a powerful collection of sensitive subjects, which were not only expected but also surely intended to lead to consequences.