China’s Ai Weiwei has recently been removed from the creative scene. Absent and yet present, he is an artist whose work has become renowned all over the world in recent years.

Special attention was given to Ai particularly because of his creative criticism and involvement in social and political questions concerning China. In 2007, for example, at the Documenta 12, one of Europe’s biggest art fairs, Ai provoked his public by inviting along 1001 Chinese compatriots. His statement was simple yet powerful. Ai’s experiment raised awareness about how China is booming, but at the same time, about how it remains separated from the West.

Despite the regime’s restrictions, new art in China has found diverse channels of expression in the years since 1989, ranging from direct criticism of Western consumption, to mocking stereotypes of Maoist propaganda or to addressing the weaknesses of the communist regime. Ai Weiwei belongs to the latter group of creatives. He is one of China’s best-known artists and at the same time one of China’s most despised dissidents.

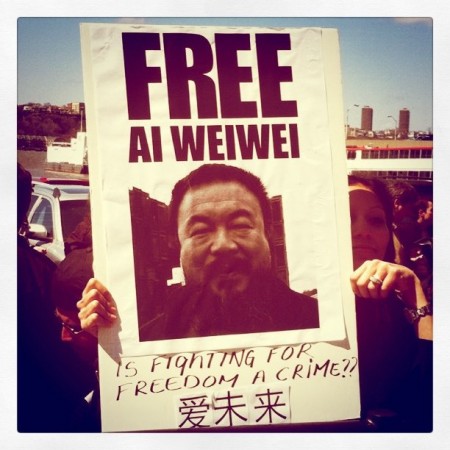

Ai’s arrest at the beginning of April 2011 was met with consternation by the international public. Yet the most recent wave of repression affected not only Ai, but the entire Songzhuang art district, in the eastern suburbs of Beijing. This community of artists had elected a suggestive name for their latest exhibition: Sensitive Zone. The exhibition was in itself a provocation, a powerful collection of sensitive subjects, which were not only expected but also surely intended to lead to consequences. What was it in this exhibition that drew the attention of the Chinese authorities? Whatever it was, the consequences were harsh: Cheng Li, for example, was sentenced to two years in a labor camp.

The repression wave was an indirect but obvious statement of what the Chinese fear most. One interpretation is apparent: Artists in China are the most relevant transmitters of the scent of the protests and liberation movements in the Arab World. “Bury Jasmine”, a performance act by artist Huang Xiang, in which he buried his own body covered in jasmine flowers, had a clear metaphoric message and was a direct reference to the revolutions in the Arab world.

Late March 2011 Ai Weiwei had finally come to the point where he was planning a studio abroad. His resistance seemed to have come to an end. But instead of allowing him to leave and become an exiled dissident, China chose to make use of its temporary advantage and eliminate him from the scene.

It is clear that Ai was digging too deep into the country’s darkest stories. Only recently had he started to investigate the school collapses in the 2008 earthquake of the Sichuan province and to criticize the state’s negligence in providing secure buildings. Another thing that surely annoyed the authorities was that early this year Ai sent the organizers of the TED conferences a video, addressing the atmosphere of repression in China today.

As the subtlest form of protest, art is quiet, yet accusatory: a disclosed and clever critique that succeeds in trespassing the barriers of censorship. But the same things which make this critique subtle also put artists in a position of fragility and weakness. It seems there is nothing that the international public opinion and diplomatic pressure can do to change China’s mind and to ask for a mild treatment of China’s most gifted and creative. Declarations such as the most recent one by Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, which describe Beijing’s human-rights record as “deplorable” remain without impact or response.

But critical art in China is only at its beginning and critical acts are on the rise. While artists’ freedom of expression is being cut off, China is nurturing an already fertile ground for provocative art. Repression is strong, but the opposition is active and criticism alive. US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton is right about one thing: history is against governments that resist democracy. Artists like Ai Weiwei will prove themselves right.

For a wealth of background information and analysis on Human Rights in China, please visit the ISN Digital Library.