This article was originally published by Global Policy on 4 May 2016.

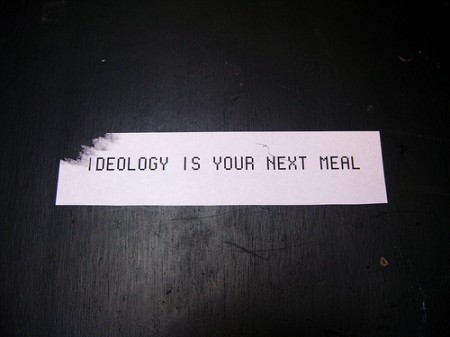

Why do certain ideas and political paradigms endure while others become obsolete or are rejected?

This question has preoccupied political and philosophical scholarship for millennia. This article puts forward four conditions for the survivability of ideas. It argues that modern tools for understanding human nature, such as those offered by neuroscience, provide us with unprecedented insights about human predilections and needs. Based on these findings, we can better conceptualize why some ideas thrive while others do not and their possible implications to international relations. The human need for dignity is central to this explanation: no ideas can thrive if they do not guarantee and safeguard human dignity.

In 1859, Darwin introduced the concept of natural selection in On the Origin of Species, and J.S. Mill explored the flourishing of ideas in On Liberty. In Darwinian natural selection, features that do not contribute to the function of the individual vanish over the course of generations, as bearers of such traits lack the reproductive fitness to pass those features on to their offspring. Mill applied a similar argument to ideas: good ideas would survive the rigors of critical debate, but there were no means of discovering which ideas would endure apart from testing them. In my attempt to continue this debate, I turn to neuroscience. Advances in neuroscience and brain-imaging inform us about underlying predilections in our nature, which indicate that we will be more likely to choose and validate certain ideas over others. My task here is to unpack this premise and to do so by looking at four prerequisites for the selection of ideas.