3-D printing, while unknown to most of the public, has been around for quite a while. Its industrial applications range from rapid prototyping and archaeological reconstructions to medical uses in implant technology and custom-fitted hearing aids. Now, the technology is becoming affordable for the average consumer: while an industrial-strength 3-D printer that can use materials like bronze-infused steel, or even titanium, still costs more than $10,000, desktop machines for printing hard plastics are being sold in kits available for little over $1000.

These machines, sold by small companies such as makerbot or made available as open- source blueprints (as in the RepRap project), bring desktop manufacturing into the homes of interested individuals all over the world. With enthusiasts using the new tools to design and manufacture things of all shapes and sizes, websites such as Thingiverse have sprung up, where blueprint files can be shared. Available blueprints range from the whimsical (think TARDIS-shaped lollipop mold, for Doctor Who aficionados) to more practical gadgets, like fully-functioning pliers or pad-locks. With the right files in hand, objects can be reproduced on a 3-D printing machine. Lately, companies like shapeways and i.materialise have started offering professional 3-D printing for homemade files, which brings advanced materials such as clear plastics, bronze-infused steel and titanium to the consumer market.

While all this is great — and even, as Time Magazine put it, ‘game changing’ — problems are beginning to arise. Copyable object files raise new issues that copyright law is ill-equipped to handle, and another troublesome area is the status of civil liability arising in connection with objects made from files uploaded or modified in the open-source domain.

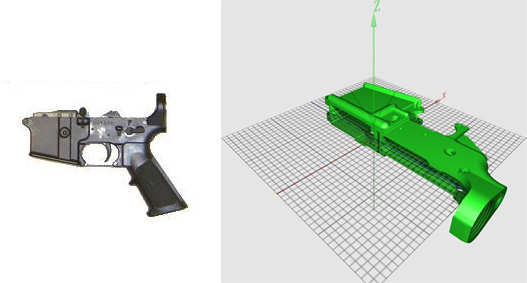

But perhaps the most worrying development is something that has just appeared on the radar: the possibility of printing weapon parts from home to circumvent government regulations. One notable example is the printable blueprint for the lower receiver of an AR-15 rifle (known in the United States as the M-16). Because this component is such an integral part of the AR-15 rifle itself, in the United States it is legally considered a firearm for purposes of sale and manufacture. With the AR-15 lower receiver 3-D object file, however, freely available on the thingiverse website, anyone can manufacture this part at home. A quick search of the site also reveals files for an AR-15 magazine and rifle grip. Other files, such as this silencer for air-pressure weapons could easily be adapted to more sinister purposes.

While the applications of 3-D printing technology seem limitless, from printing actual, living organs to printing houses in concrete, we must be mindful of how this potentially game-changing technology will affect our security. From the rifle components just described to concealable weapons made of plastic to ATM skimmers, the endless possibilities will not all be benign and should not all be legal. But this means that legislators have some catching up to do, as no part of this process — of making a blueprint for a weapon, uploading it to a site, or downloading it — is in any way illegal at present.

One reply on “Would You Download a Weapon?”

Our partner organization, the Atlantic Council, has recently published a paper examining 3D/additive manufacturing: it is available here – http://www.acus.org/publication/could-3d-printing-change-world