This article was originally published by Geopolitical Futures on 26 January 2018.

Less than a week after Turkey began its invasion of Afrin – the northwestern pocket of Syria that borders Turkey and is controlled by the Kurdish People’s Protection Units, or YPG – NATO has voiced its consent of the operation. On a visit to Istanbul, NATO Deputy Secretary General Rose Gottemoeller told a Turkish newspaper that NATO recognizes the threat terrorism poses to Turkey. While the language Gottemoeller used wasn’t highly specific, she was referring to the threat posed to Turkey by the Kurdistan Workers’ Party, or PKK, an internationally recognized terrorist group. Over the past three decades, the PKK has led an insurgency that has caused the deaths of roughly 40,000 people.

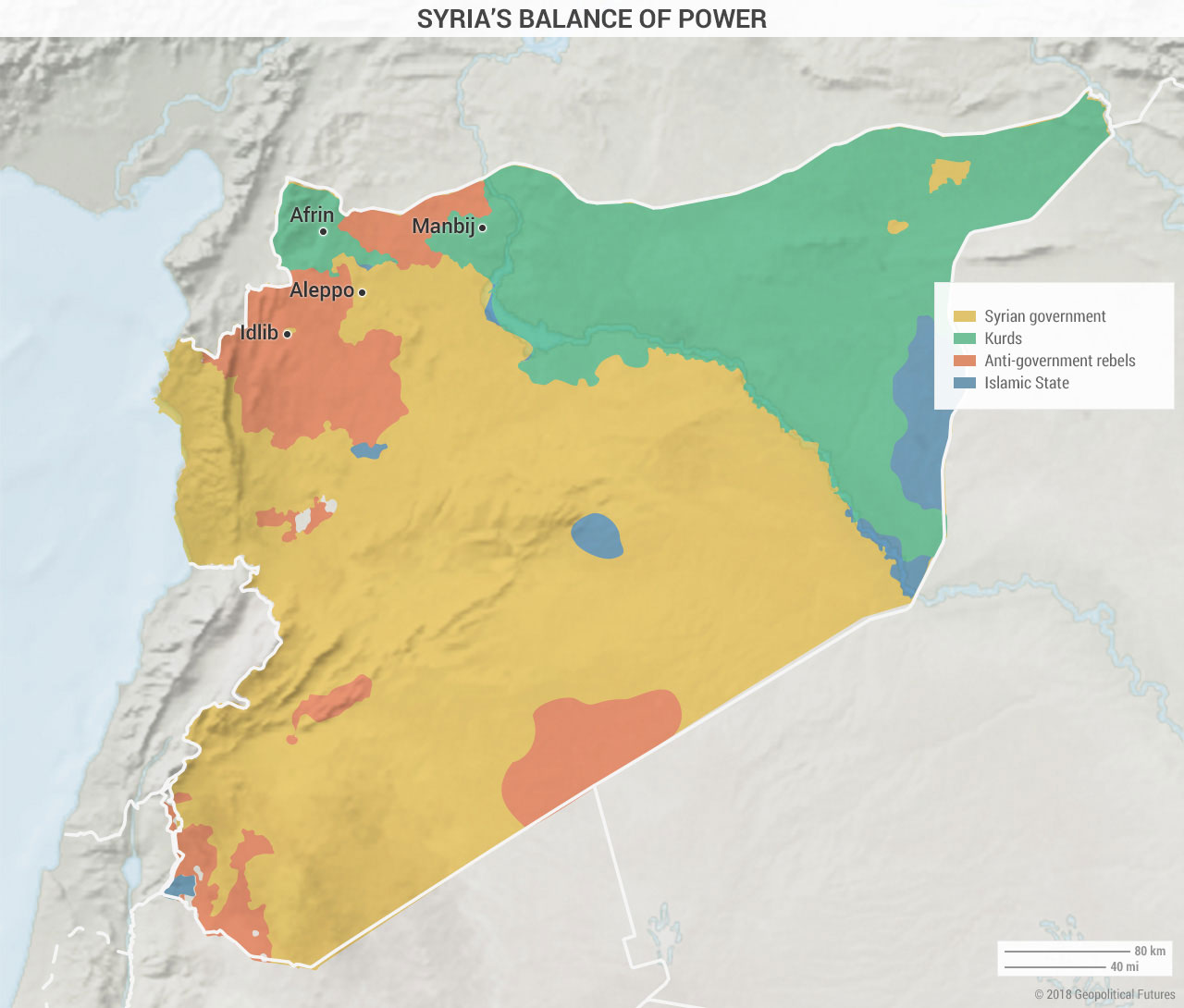

Turkey sees Afrin as a security threat due to the presence of the YPG, considered by Turkey to be a branch of the PKK. The YPG having control over an area that sits on the border with Turkey means it could potentially launch more destructive attacks on Turkish soil. For Turkey, any concession to a Kurdish group – militant or otherwise – is a slippery slope that could lead to greater Kurdish demands for independence.

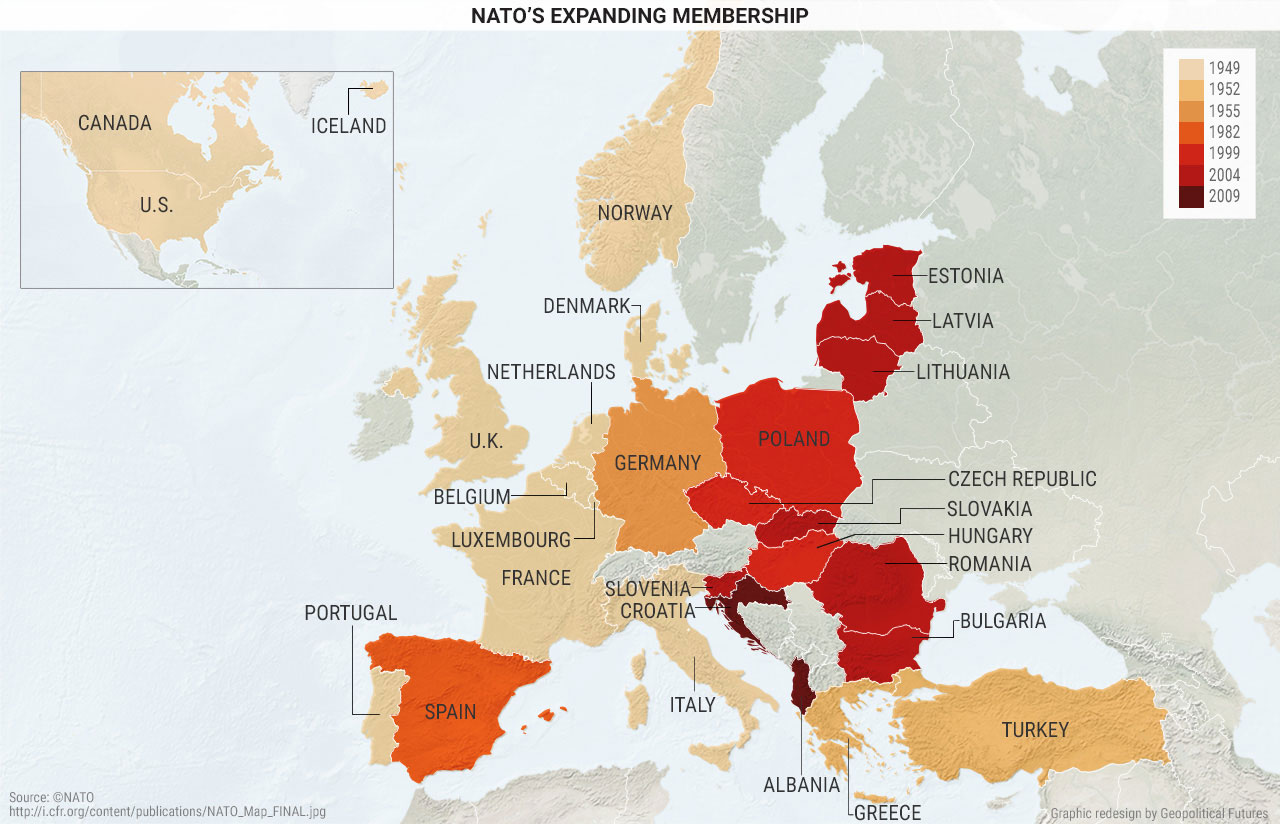

NATO’s announcement sheds some light on an underlying reality: that NATO benefits from Turkey’s intervention. While the NATO deputy secretary general said the threat posed to Turkey was from terrorism, NATO’s true fear is Russia. If President Bashar Assad, a Russian ally, were to reassert control over Syria, it would place Russia in a stronger position in the Middle East. A Syria fully controlled by Assad – no longer in need of Russian military support – would also let Russia withdraw its forces from Syria. While Russian President Vladimir Putin would desperately like his declared victory to be real, to secure his public relations boon and get out, a war that continues to threaten Russia’s ally continues to threaten the purported success of Russia’s intervention. Meanwhile, Europe is quite content to keep Russia tied down in the Middle East, drawing at least part of Russia’s focus and military hardware away from its European borders.

Of course, NATO would like to keep Russia tied down with minimal or preferably no involvement of its own. But the elephant in the room whenever a NATO ally is threatened is Article 5, the lynchpin of the NATO alliance, which stipulates that an attack on one NATO member is an attack on all, and therefore warrants a collective military response. Article 5 has been invoked only once – when the U.S. was attacked in 2001 by al-Qaida. Many will question whether the PKK attacks on Turkey are a substantial threat and, therefore, are asking: Could Turkey make the argument to invoke Article 5 and involve the rest of the alliance in Afrin?

The answer is simpler than it may seem at first: It doesn’t matter. Neither Turkey nor the rest of Europe wants NATO to get involved in Turkey’s Afrin operation. As Turkey’s power grows and enables greater projection of power into the Middle East, it will try to take advantage of opportunities to act on its own. The key for Turkey is independence of action; it does not want its options dictated to it by others, whether the U.S. or NATO. If NATO were to get involved in the Afrin operation, even if it were supporting Turkey, it would nevertheless introduce a myriad of conflicting command structures and interests. It would complicate Turkey’s freedom to maneuver and ability to unilaterally pursue its own military objectives, which include not just eliminating the threat of terrorism on its border, but also checking Iranian and Russian ambitions in Syria.

NATO also benefits from Turkey’s intervention in Afrin. Much like the U.S., NATO fears Russian expansion. It also fears Iranian expansion but to a lesser degree than the U.S. does (in part due to the business opportunities presented by an open Iranian economy). If Turkey takes Afrin – which currently seems like the most likely outcome given the balance of forces between Turkey and the Afrin defenders – that would put in Turkish control (including its proxies) a contiguous swath of territory that surrounds Aleppo on three sides. Even if Turkey did not immediately move to capitalize on this tactical situation following the acquisition of Afrin, the fact that this land would be in Turkish possession still poses a risk to Assad, Russia’s regional proxy. NATO is more than happy to let Turkey do this on its own and not have to risk its soldiers in the process.

Notably, NATO’s interests in Turkey’s intervention align closely with those of the United States. For the U.S., despite its public rhetoric urging Turkey to take caution in its intervention, ultimately it is content to let Turkey check the powerful position that Iran has acquired in the course of the Syrian civil war. The European contingent of NATO is predominantly concerned with Russia, and Turkey capturing Afrin would place Russia in a difficult situation. Russia has no desire to confront Turkey directly, at least not right now (and, for that matter, neither does Turkey want to confront Russia directly). But Russia wouldn’t mind a situation in which Turkey and Iran challenge one another in Syria, as long as Turkey remains tied down in the struggle and doesn’t emerge victorious.

Turkey’s operations in Syria, however, depend heavily on a number of proxy groups in the west of the country – such as the Free Syrian Army – that Russia has continually identified as one of the core security threats to the Assad regime. The FSA has therefore been one of Russia’s primary targets. If Aleppo were to become surrounded, Russia would be compelled to continue supporting Assad by attacking Turkish proxies, but would be careful to avoid attacking Turkish soldiers. Most important for Russia, such a scenario would further ruin the image of a victory that Putin was hoping to walk away with, and would risk tying Russia down in the Middle East for an indefinite amount of time.

Russia’s prolonged involvement in the Middle East with no easy out would be a clear win for NATO, especially if it doesn’t need to commit any of its own forces to bring this about. Clearly, this wouldn’t eliminate the security threat that Russia poses to Europe’s eastern flank, but it would be an ongoing financial strain on Russia, which is already struggling with economic challenges. NATO’s inaction will amount to tacit support of Turkey’s intervention in Afrin. But it’s happy to sit this one out.

About the Author

Xander Snyder is an analyst at Geopolitical Futures.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS website.