| “Dear incredible Avaazers, Just a few hours ago, our community reached 10 million people!” |

Last week’s announcement by Avaaz, an online pressure group, speaks volumes for the continued enthusiasm for a form of political action that requires little more than a couple of mouse clicks. Once you’ve registered on a site like Avaaz, all you need to do to support a cause is enter your email address and click a button – or two, if you want to advertise your deed on your Facebook and Twitter accounts.

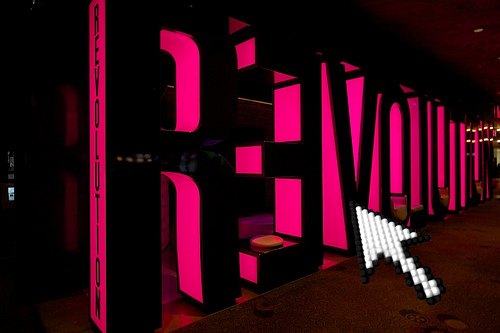

Clicktivism, as skeptics often call it, is the “act or habit of using the internet as a primary means of influencing public opinion on matters of politics, religion or other social concerns.” Organizations devoted to this form of protest increasingly try to translate online activity into action outside cyberspace – prompting followers to call, send post cards, or attend sit-ins and other ‘live’ forms of demonstration. But the vast majority of their actions remain confined to the internet.

This has sparked a heated debate about the sense and non-sense of web-based forms of political protest. Supporters point to the success stories and assert that online activity can have real world impact. But critics maintain that, while digital activism is making it easier for activists to express themselves, that expression makes less of a difference. Because organizations like Avaaz, MoveOn or 38Degrees use sophisticated email software that allows extensive tracking, marketeering technocrats may be reducing political engagement to a state of meaningless idleness. Evgeny Morozov, author of The Net Delusion, even infamously renamed the movement ‘slacktivism’ – feel-good activism with zero political or social impact.

Looking at events from Tahrir to Times Square, however, it hardly seems necessary to worry that internet-native generations will become increasingly apolitical and unengaged. And although these protests would definitely have taken place without the internet, social media has been a catalyst by facilitating the organization and mobilization of protesters.

But back to clicktivism: instead of seeing it as a lazier version of staging a protest, perhaps it should be seen as an improvement on previously passive media consumerism. Having one-way conversations with your television set will never give voice to public grievances, while a massive response to an online petition may at least give decision- makers a vague idea of the unpopularity of their actions, and of how many are watching. That obviously doesn’t make other forms of protest redundant, but can help put the spotlight on those “tipping-point moments of crisis and opportunity” — just more conveniently, and, sometimes, more effectively.