The role that social networks have played in the ‘Arab Spring’ has been much-discussed in recent months, and many a Master’s thesis these days must be written on how the Internet – and social media in particular – is changing political dissent movements. Given the Internet’s ability to quickly disseminate information, and to allow like-minded individuals to find each other and mobilize support for a cause, one might assume that Facebook and other forms of social media would advantage popular struggles against centralized power — and that switching them off would be a tactic of choice among weary dictators.

Quite the opposite, says Navid Hassanpour, who has used a dynamic threshold model for participation in network collective action to analyze the decision by Mubarak’s regime to disrupt the Internet and mobile communications during the 2011 Egyptian uprising. The disruption of the services, he claims, exacerbated the unrest in at least three major ways:

- It affected many otherwise apolitical citizens unaware of or uninterested in the unrest;

- it brought about more face-to-face communication, which increased the number of people in the streets;

- and, through new hybrid communication tactics, it effectively decentralized the rebellion, making it harder to control and repress.

He concludes that “full connectivity in a social network can hinder revolutionary action”, which caused the New York Times to comment that ‘mass media, including interactive social-networking tools, make you passive, can sap your initiative, leave you content to watch the spectacle of life from your couch or smartphone. Apparently even during a revolution.’

|

It’s only human to crave distraction, especially in times of crisis. Still, I believe it’s more a matter of timing: once a movement has gained momentum, abrupt media disruption may simply radicalize things further.

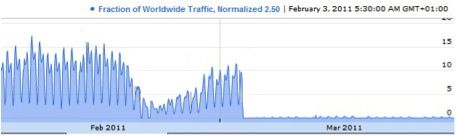

In that regard, it’s interesting to look at the approach chosen by the Libyan government*, as described by Jim Cowie in his blog on what Libya learned from Egypt. Other than in Egypt, Libyan authorities slowed the stream of traffic, first to a trickle and then to a few meager drops, but never took the net down entirely.

The Internet was then kept in a ‘warm standby mode,’ which left citizens cut off for three to five months, depending on where they lived. In July, Google first showed a minor increase in traffic, and, on 21 August, all Google services were at least partially accessible once again.

Describing the Battle for Tripoli’s Internet, Cowie asks, rhetorically: “Why would the government turn the Internet back on in the middle of an armed uprising? To get people to stay at home and catch up on five months of email?”

Hassanpour’s research would suggest precisely that. In a last-ditch attempt to save his embattled regime (and echoing what we saw in Egypt), access to the likes of Facebook, Twitter and Skype may have been used against the people — in an attempt to suffocate a revolution, rather than to facilitate or inspire one.

*Obviously a comparison between Egypt and Libya should be treated with caution, not least because only 6% of the population in Libya have Internet access, while it is 24% in Egypt.

2 replies on “Media Disruption in Times of Unrest”

@Silvio: my point exactly.

To conclude, “full connectivity in a social network” does not “hinder revolutionary action”, but cutting it simply adds fuel to the fire. Or did I get it the wrong way?