This article was originally published by the Centre for European Policy Studies (CEPS) on 6 July 2017.

The Italian Prime Minister, Paolo Gentiloni, last week issued a plea to his European colleagues for help in dealing with migrants crossing the Mediterranean. Combined with the threat to close off Italian ports to vessels disembarking migrants from search and rescue operations in the Mediterranean Sea, the Italian government called for more burden-sharing generally in distributing migrants across the EU. This entreaty was reiterated on Sunday, July 2nd, in a meeting of Justice and Home Affairs ministers from Italy, France and Germany. It is certain to feature predominantly at the EU meeting of Justice and Home Affairs ministers on July 6th and 7th.

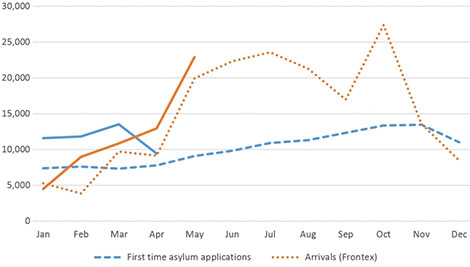

The background to this call is a marked increase in irregular crossings from Libya to Italy – the so-called Central Mediterranean route – a situation that has been complicated by reports of more than 10,000 refugees and migrants arriving in Italy in recent days. Statistics from Frontex (the EU’s border agency) indicate that arrivals and asylum applications are roughly 25% higher in Italy than at the same time last year (see Figure 1) – a figure that is likely to increase with the release of data from June. First-time asylum seekers in the period from January to April are up by 50%. If arrivals follow a similar pattern to that of previous years, where summer is the prime time for irregular Mediterranean crossings, the EU is likely to hear from Italy again rather soon. Another reason for the plea lies in the lack of implementation – to put it mildly – of the one-off relocation scheme decided in 2015, whereby 35,000 asylum seekers located in Italy are to be distributed among member states before September of this year. Currently, only 7,300 have left Italy under this scheme (EC, 2017).

Figure 1. First-time asylum seekers in Italy and arrivals (Frontex) January 2016 to May 2017

Background: Does Italy need help?

The requests for assistance have to be seen in context.

First, even if Mediterranean crossings exceed 200,000 people this year, this should not be a fundamentally unmanageable number for a country the size of Italy (Sweden, with one-sixth the population of Italy, took in 150,000 asylum seekers in 2015). Italy has received around 9% of the total number of asylum applications in the EU25[1] over the last four years (2013-2016); less than Italy’s 14% population share of the EU25.

Second, not everyone crossing the Mediterranean asks for asylum in Italy. Since 2012, around 300,000 people out of a total of 500,000 arrivals have applied for asylum (see Figure 2). This means that Italy’s share of illegal border crossings could be much higher than its share of asylum applications. In the past, the difference was due to a lack of fingerprinting and documenting of new arrivals, but this problem seems to have been fixed last year.

Figure 2. First-time asylum applications in Italy and mediterranean crossings, 2013-2013

Would the Commission’s proposal for burden-sharing help?

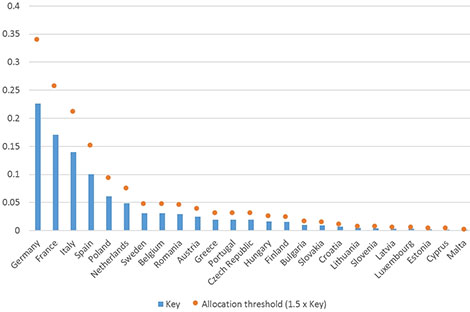

A year ago the European Commission proposed a recast of the Dublin Directive – Dublin IV, as it is known, which has as a core element a burden-sharing scheme among EU countries (EC, 2016). The suggested scheme would define a ‘reference key’ of asylum seekers among EU countries that is based on 50% of the share of total GDP and 50% of the population size. If the number of asylum seekers coming to a country exceeds 150% of the number determined under the reference key, a mechanism of relocation of asylum seekers to other EU countries kicks in. The relocation is performed in proportion to the distribution key.[2]

The proposed directive has met resistance in the Council and no agreement was concluded under the Maltese presidency, despite it being a priority. The prevailing narrative is that burden-sharing is blocked primarily by the Visegrad countries (the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia), although there is probably little appetite for what is de facto an unlimited commitment to burden-sharing in other countries either.

More importantly, even if the Commission’s proposal had been in place it would not have helped Italy greatly. Italy is a large country with an average GDP. Italy’s share in the distribution key for EU25 countries (excluding the UK, Ireland and Denmark) is thus 14%, exceeded only by Germany (23%) and France (17%) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Distribution key according to Dublin Recast proposal, 2016 values

The size of Italy’s reference key means that no asylum seekers would have been relocated from Italy in the period from 2009 to 2016 (Figure 3). It is therefore doubtful that the one-off relocation for Italy (and Greece) decided in 2015 would have happened under a reformed Dublin system, based on the Commission’s proposal. Rather, a sizeable number of refugees would have been relocated to Italy from other EU countries, primarily from Germany and Sweden, in 2015 and 2016.

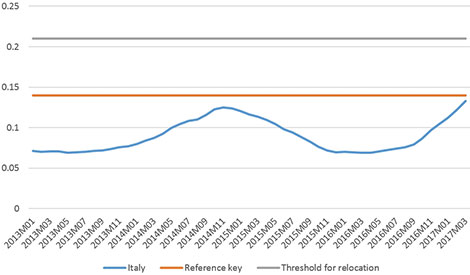

With this year’s increase in number of asylum applications (based on the latest data up to March 2017, still far below the number of crossings) Italy is getting close to the reference key share, but no burden-sharing would take place (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Italy’s share of first-time asylum applicants for 2013M1-2017M3, distribution key (EU25, excluding the UK, IE and DK) and relocation thresholds

Furthermore, many of those arriving at Italy’s shores seeking asylum are unlikely to be eligible for protection status. Eight African countries – the Côte d’Ivoire, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Mali, Nigeria, Senegal and Sierra Leone – made up more than 50% of first-time asylum applications (5,330 of 9,560) to Italian authorities in April 2017 (latest available data). These countries had an average recognition rate of less than 20% across the EU in 2016.

These figures are important for the degree of burden-sharing available in the Commission’s proposal. It envisages that member states conduct inadmissibility tests of asylum seekers, i.e. determining if they come from a safe third country or country of origin to which they can be returned. Asylum applicants whose application has been deemed inadmissible cannot be relocated as part of the burden-sharing scheme, although they do count towards the reference key and threshold for relocation. This is in order not to transfer individuals who are to be returned to a third country. Hence, in the current case of Italy, most asylum seekers from these eight African countries would most probably not be included in any feasible future relocation mechanism (they would fail the initial, and much contested, admissibility criterion featured in the Commission’s proposal). The same caveat would apply to the ‘coalition of the willing’ approach that we proposed elsewhere (MEDAM, 2017).

Going forward: Work-for-readmission agreements

Short of redirecting individual vessels carrying migrants to Marseille, Sardinia or Palma (which appears to have been discussed at the July 2nd meeting, but now seems to be off the table), increased financial burden-sharing and a few relocation pledges following from the 2015 decision, there will be little help on offer to Italy. The proposed ‘code-of-conduct’ for NGOs operating search and rescue operations will probably have little effect.

What is left is to redouble efforts to seek new ways to bring down the number of people arriving to Italy. Returning people who are not eligible for asylum back to their home countries is central to reducing the number of people crossing the Mediterranean. Doing this effectively will in itself lessen the incentive to undertake the perilous journey to the EU, which subjects migrants to an increasing number of human right violations in Libya (UNHCR, 2017). This is irrespective of the stance one takes in the debate on the search and rescue (SAR) operations carried out close to the Libyan border, by both private and national actors.

Administering readmission, however – i.e. returning people – is fraught with difficulty (Carrera et al., 2016). Under its ‘Partnership Framework on Migration’ the European Commission is in dialogue with a number of focus countries – Niger, Nigeria, Mali, Senegal, and Ethiopia – from where people attempt the Central Mediterranean route. There is a need to push for further negotiations and expand these partnerships, the so-called ‘compacts’. First, pathways to legal migration have to be provided in return for smoother readmission to provide firmer incentives for third countries to comply with return and readmission agreements. This requires a number of member states to put forward schemes for legal migration, which can fit within the framework of the compacts. One way forward is to build and maintain training facilities in key countries, financed by the EU, where a percentage of those trained are offered (temporary) work permits to the EU (see Clemens, 2014). Such ‘work-for-readmission’ agreements can be done in a forward-looking manner so that only new arrivals after a given date are subject to readmission (ESI, 2017).

Admittedly, these proposals are no panacea but, given the state of the EU asylum policy framework, can we afford not to try?

Sources

Carrera, Sergio, Jean-Pierre Cassarino, Nora El Qadim, Mehdi Lahlou, and Leonhard Den Hertog (2016), “EU-Morocco Cooperation on Readmission, Borders and Protection: A model to follow?” CEPS paper in Liberty and Security in Europe, No. 87.

Clemens, M. A., (2014), “Global Skill Partnerships: A Proposal for Technical Training in a Mobile World”, CGD Policy Paper 40, Washington DC: Center for Global Development.

European Commission (2016), “Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council establishing the criteria and mechanisms for determining the Member State responsible for examining an application for international protection lodged in one of the Member States by a third-country national or a stateless person (recast)”, COM(2016) 270 final.

European Commission (2017), “Member States’ Support to Emergency Relocation Mechanism”.

European Stability Initiative (2017).

MEDAM (2017), “MEDAM Assessment Report on Asylum and Migration Policies”, Kiel: Ifw.

UNHCR (2017).

Notes

[1] The EU25 excludes the UK, Ireland and Denmark, which do not participate in the area of asylum and migration on a mandatory basis.

[2] Each country only takes part in the scheme until its total number reaches 100% of its distribution key.

About the Authors

Mikkel Barslund is Research Fellow and Lars Ludolph is Researcher in the Economic Policy unit at the Centre for European Policy Studies (CEPS).

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit our CSS Security Watch Series or browse our Publications.