Sixty-five years ago, on 20 July 1944, during the darkest days of German history, a few good men brought back a small spark of light to the conscience of a nation torn by war and involved in history’s most unprecedented mass murder. The story is well-known. So is the result: the attempt to remove Hitler from power with the help of his own contingency plan “Valkyrie” tragically failed.

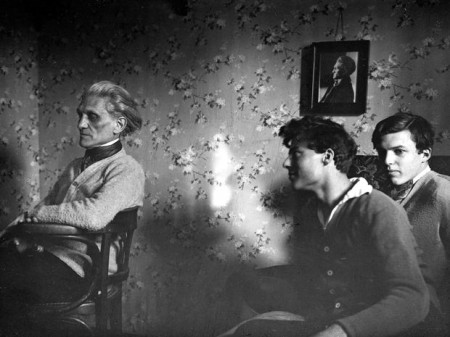

What might not be so well-known is that Count Claus von Stauffenberg, according to Cambridge historian Richard J Evans, “found moral guidance in a complex mixture of Catholic religious precepts, an aristocratic sense of honour, Ancient Greek ethics, and German Romantic poetry. Above all, perhaps, his sense of morality was formed under the influence of the poet Stefan George, whose ambition it was to revive a ‘Secret Germany’ that would sweep away the materialism of the Weimar Republic and restore German life to its true spirituality.”

The key to understanding that “Secret Germany” (as cryptically elaborated in a poem by the same title, which was written around 1910, but hermetically kept from the public until 1928) is the idea that only the poet with his charismatic authority can voice the arcane without revealing it. It is him being the “spiritus rector” who deepens the inner reflections of his disciples, who awakens their intellectual and spiritual sensitivity, so his word is followed by their action.

Hugo von Hofmannsthal, yet another early and prominent disciple of Stefan George, reasons: “Nothing becomes reality in the political life of a nation that was not present in its literature as spirit.”

As several authors have pointed out recently, this very much applies to Stauffenberg’s steadfast will to act, an obsession deeply rooted in the ultra-refined and prophetic poetic cosmos of Stefan George. Consequently, Stauffenberg holds the death watch for George in 1933, citing poems on the “master’s” grave, whereas his brother, Berthold, becomes George’s literary executor.

It is reported that while still a child, Stauffenberg ardently played the role of Stauffacher in a school’s performance of Schiller’s epic “Wilhelm Tell.” Decades before the roles will change, he declaims:

“Yes! there’s a limit to the despot’s power!

When the oppressed looks round in vain for justice,

When his sore burden may no more be borne,

With fearless heart he makes appeal to Heaven,

And thence brings down his everlasting rights,

Which there abide, inalienably his,

And indestructible as are the stars.

Nature’s primeval state returns again,

Where man stands hostile to his fellow-man;

And if all other means shall fail his need,

One last resource remains—his own good sword.”

Only a few days before the plot, Stauffenberg says: “It is now time that something is done. But the man who has the courage to do somehting must do it in the knowledge that he will go down in German history as a traitor. If he does not do it, however, he will be a traitor to his own conscience.” And so he decides to act, against his military oath and religious conviction, yet in accordance with the utmost soldierly virtue.

Around midnight on 20 July 1944, Colonel Claus Philipp Maria Schenk Graf von Stauffenberg, age 36, father of four children, husband to a pregnant wife, is taken to the courtyard of Berlin’s Bendlerblock, standing face-to-face with a firing squad, awaiting his execution under martial law. He is wearing a gold ring inscribed with “finis initium,” re-phrasing George’s poem “I am an end and a beginning.” While the squad is reloading and aiming at him, Stauffenberg shouts out: “Long live our Secret Germany!” As a last dramatic gesture of defiance, Werner von Haeften, Stauffenberg’s adjutant, throws himself into the path of the bullets.

Shots silence his echo.

In the immediate aftermath, at least 7,000 alleged conspirators are arrested by the Gestapo of which around 5,000 are executed (among them Claus’ brother Berthold). In the nine months between Stauffenberg’s execution and Hitler’s suicide which symbolically marks the end of World War II, as many people die in vain as in the four years since the beginning of the war.

Today, I commemorate an end and a beginning.