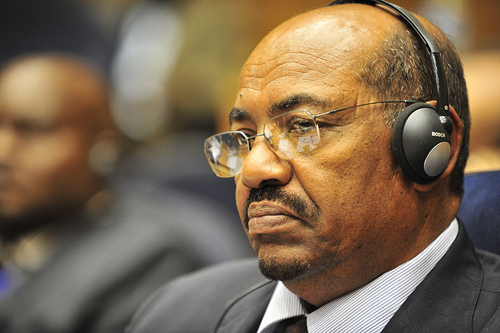

Attempts to isolate and marginalize Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir have been mixed at best. The man many people believe is ultimately responsible for the violence and misery of Darfur – and who has been indicted by the International Criminal Court (ICC) for it – has worked tirelessly to show that, as a head of state, he can still galavant across the globe to international conferences and state meetings.

Of course, Bashir hasn’t always been able to go wherever he wants. He hasn’t visited a ‘Western’ state since he was indicted by the ICC in 2008. While he has visited ICC member-states, notably Chad and Kenya in 2010, he is still severely constrained in his movements and Malawi, a member-state which originally let him visit in 2011, has since declared that he is unable to do so again.

As many readers will know, the marginalization of perpetrators of atrocities is a central argument for proponents of international criminal justice. In brief, the argument suggests that investigations and the issuance of arrest warrants against international criminals will isolate them, both within their networks of power such as a government or a rebel group as well as within the international context. In the long-run, it is hoped that this marginalization can ultimately fill the docks of international criminal tribunals and deter the commission of crimes.

With Bashir’s travels across the globe, critics have been quick to point out that international criminal justice is impotent. They often hold up a handful of examples of places Bashir has visited which, they maintain, run counter to any marginalization effect. Thus, they say: ‘there you have it: the marginalization effect of international criminal justice doesn’t work.’ On the other hand, proponents often seek alternative examples where marginalization appears to have been successful. The best – and most popular – example of this are the cases of Ratko Mladic and Radovan Karadzic, who were indicted by the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) and effectively marginalized from the Dayton peace process. Despite fears that they would spoil the peace process, both Mladic and Karadzic were eventually arrested and are now facing trial at the ICTY in The Hague.

The problem is this: like the other effects of international criminal justice, the marginalization/isolation function is bound to have mixed results. This is because the ICC, or any other tribunal, cannot create effects within a vacuum. Other factors, especially political factors, calibrate the effects of international investigations and arrest warrants.

In Bashir’s case, he is able to travel to some states and not to others. Indeed, traveling outside of Sudan is likely more important to him now than before the ICC arrest warrants against him were issued as he can claim that his international visits illustrate his standing as a sovereign head of state and marginalizes the Court rather than himself or his regime. That being said, Bashir’s travel plans are undoubtedly curtailed by the ICC. But his marginalization is also affected by international politics. Not all states care equally about the ICC’s warrants against Bashir or about alleged crimes in Darfur, for that matter. China certainly had no qualms about inviting Bashir to visit and in investing huge sums into Sudan’s economy. The US has been willing to work with Bashir’s regime, in part to ensure the peaceful separation of South Sudan from the North. After receiving considerable support from Khartoum during the Revolution, Libya’s National Transitional Council was quick to welcome Bashir after the fall of Gaddafi while the rest of the world remained virtually silent. Of course, if we consider the self-interests of states who welcome Bashir, the Sudanese President’s visits are unsurprising. But the same can’t be said if a UN Secretary General were to meet Bashir.

The UN has typically ensured that envoys and diplomats met with Bashir and other members of his regime in order to discuss issues of concern to the international community. Since the ICC issued its initial arrest warrant against Bashir in 2008, UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon has avoided any direct meetings or confrontation with Bashir. Yet last week, the Sudan Tribune reported that Ban Ki-moon did what many believed was unthinkable: he met, face-to-face with Bashir in Tehran, in what a UN spokesperson subsequently described as “a brief greeting and handshake.”

As Eric Reeves points out, this development is even more odd because Ban Ki-moon met Bashir in the context of Sudan preparing to take its place on the UN’s Human Rights Council (yes, you read that correctly). Of course, it also comes in the context of increasing evidence that Sudan is harbouring Joseph Kony, perhaps the world’s most notorious international criminal, in Darfur.

Ban Ki-moon’s meeting with an allegedly genocidal leader is different from Bashir’s visit in China or his visit to Chad. After all, UN Secretary Generals are normative actors who we expect to extol the virtues of international justice and peace from their secular pulpit. To many, the UN Secretary General represents efforts to achieve a more just international society of states. While critics and opponents of the UN will no doubt and vehemently disagree, for millions, the UN Secretary General is a representative of humanity or, at least, an employee of humanity. His “interests” are to promote an international system based on international justice, human rights, peace and security. “Peacebuilding” and “transitional justice” are part of his global mandate and mantra, impunity for the international crimes his enemy. It is for these reasons that Ban Ki-moon’s decision to visit, face-to-face, with Bashir is so troubling.

It is not clear whether the meeting marks “the UN’s moral rehabilitation of the Khartoum regime“. But if nothing else, the meeting between Ban Ki-Moon and Omar al-Bashir illustrates just how little interest there remains within the international community to arrest or truly isolate Bashir. Darfur seems to be on the international community’s back-burner. And that’s a significant victory for one person in particular: Omar al-Bashir himself.

Mark Kersten is creator and author of the blog Justice in Conflict. He is currently a PhD student in the International Relations Department at the London School of Economics, researching on the implications and effects of the International Criminal Court’s investigations on peace processes and negotiations in Libya, Darfur and northern Uganda.

This is a cross-post from Justice in Conflict

For further information on the topic, please view the following publications from our partners:

UN Accused of Caving in to Khartoum Over Darfur

For more information on issues and events that shape our world please visit the ISN’s Security Watch and Editorial Plan.