This article was originally published by the Central Asia-Caucasus Institute and the Silk Road Studies Program on 10 May 2017.

Turkey and Russia have recently both turned to an aggrieved nativism that delegitimizes democratic opposition. This nativism is nationalist, anti-elitist, protectionist, revanchist/irredentist, xenophobic and “macho”. Despite three decades of post-Cold War transition both countries have failed to be at peace with themselves; have not been able to adjust to their neighboring regions and come to terms with their respective histories.

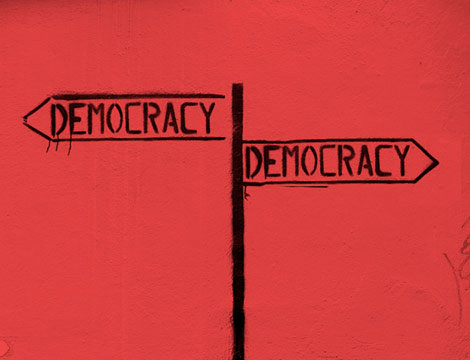

Background: The world political order is under great duress. From Russia to India, Turkey to Hungary, Poland to Great Britain and France – and most recently in the United States – populist and authoritarian politics is making a strong comeback. Liberal democracy is no longer “on the march” while the once famously prophesized “end of history” now seems to be a very distant prospect. Pluralist, centrist and moderate politics are on the defensive. What we have at hand is a nativist wave, a reaction against roughly three decades of intense globalization.

A new “aggrieved nativism” that is thoroughly opposed to liberal values such as pluralism, freedom of expression and minority rights is appealing to majorities in many countries. Turkey and Russia are two prominent examples of this international trend. Populism, authoritarianism bordering on dictatorship, virulent nationalism imbued with a distinct contempt for liberal values has gained traction among the electorate in these two countries.