This article was originally published by the Institute for Security Studies on 4 October 2016.

The AU is taking a well-timed look at how arms embargoes can be better implemented.

Arms embargoes are the most common type of sanction currently applied by the United Nations (UN), and one of the five main types of targeted or smart sanctions (others are diplomatic sanctions, travel bans, asset freezes and commodity interdiction).

The key aim of smart sanctions is to raise the regime’s costs of non-compliance (with the sanctions) without bringing about the wider suffering often associated with comprehensive sanctions, such as trade bans.

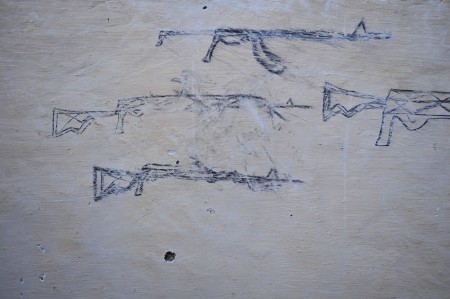

How effective these embargoes are in Africa is the subject of much debate; not least because the continent has been subjected to the majority of arms embargoes since the UN’s first stand-alone arms embargo against apartheid South Africa in 1977. Since then, several African countries have faced such embargoes; some repeatedly. Liberia, for example, experienced a series of UN-imposed arms embargoes in varying degrees and forms between 1992 and 2016. Despite this, illicit weapons continued to be trafficked into the country.