This article was originally published June 17, 2014 by The Disorder of Things.

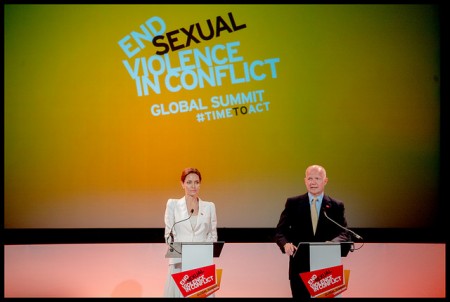

The attention lavished on sexual violence in conflict [three weeks ago] was in many ways unprecedented. As well as convening the largest ever gathering of officials, NGOs and other experts for the Global Summit on Ending Sexual Violence in Conflict, co-chairs William Hague (Foreign Secretary of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland) and Angelina Jolie (Special Envoy of the United Nations High Commissioner on Refugees) also generated very many pages – both print and digital – of commentary.

In some myopic quarters, that achievement was in itself a distraction from the really important politics of blossoming conflict in Iraq. Such views should remind us that there are still those who insist on seeing gender violence as marginal to international peace and security. Worthy, yes, “no doubt important”, obviously a cause for concern , and so on, but naturally not the real deal.

Since the Summit’s close on Friday, there have also been criticisms of a different sort. A protest on the first day drew attention to the asylum and refugee policies of Her Majesty’s Government , and the ways in which survivors of sexual violence were being mistreated on the British mainland. The Foreign Office raised awareness in part through one-dimensional stories of crazy monsters in the hinterlands of barbarism . The “weapon of war” framework was ubiquitous, but no less problematic for that (see also).

Although the Summit made space for youth delegates, UN entities, amateur hackers, foreign ministers, survivors, doctors, lawyers, celebrities, military officers and the odd NGO, academics (and our directly relevant research) were barely at the table. Some myths were therefore recycled. Delegates insisted on using rape survivors as props for their own journeys of self-discovery. I met a women in Panzi Hospital and what she told me broke my heart, etcetera. Some national representatives seemed only just to have discovered the existence of United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325, which urged the participation of women in military and political settings at all levels. That was, um, 14 years ago. John Kerry, amongst others, appeared to believe that rape in war was not yet illegal, but that we could make it so if we really put our minds to it.

The Fringe events were themselves a source of considerable disappointment. Angelina opened proceedings by assuring us that “our” institutions protected us from rape, and prosecuted it ably when it did occur, whilst “they” (we all know who) need our help because they are confined to refugee camps. There was a staged ‘trial’ of the afore-mentioned Resolution 1325, in which an all-white panel of lawyers and faux-judges, including Cherie Booth QC, took the testimony of African witnesses.

You could buy various goods made by (or meant to help) rape survivors in the “bustling” Fringe marketplace, and the official programme recommended that you “treat yourself” by doing so. All of this (including the less appalling and more considered exhibits) seemed removed from the set piece debates upstairs. If the Foreign Secretary really did refuse to meet with four Nobel Laureates – some of whom are themselves survivors of political rape – then clearly civil society (that vague but essential category) was being neglected.

Those accumulated complaints can be dismissed as relatively trivial if the Summit gets even some way to achieving its stated aim of ending sexual violence in conflict [1]. Those – including this faithful correspondent – who have argued that a wartime framing neglects extensive forms of peacetime gender violence could nevertheless rejoice at serious action on some manifestations of harm.

Summits are expensive political theatre, and exclusions, simplifications and self-serving declarations are thus to be expected. The point is what the performance enables. The Preventing Sexual Violence Initiative (under whose umbrella the Summit was convened) has already secured political declarations at several levels: a Security Council resolution last year , a G8 Communique, and a Declaration of Commitment endorsed by some 148 member-states in the UN General Assembly. Each of those reiterated existing commitments and pushed, gently, for some others (such as better recognition of men and boys as survivors). Performances of sincerity have not, then, been so far lacking. The test, as almost everybody who took a podium at the Summit also stressed, is turning rhetoric into action. #TimeToAct, indeed.

So what action was promised?

The post-Summit scene is not yet entirely clear. The most specific commitments are from individual states. As hosts, the UK promised £5 million to survivors and £1 million to the International Criminal Court’s victims trust fund. Finland pledged €2 million to UN Action and the Office of the Special Representative of the Secretary General on Sexual Violence in Conflict. Germany offered €1 million (there doesn’t appear to be any written English confirmation yet of who that is for). Given the cost of the Summit and the accumulated political pressure, these are embarrassing sums, pathetic even, in the face of the challenge and the promise. We are coming for you, the Evening Standard had declared on Angelina’s behalf (days later Hague said we were joined together in an army, no less).

The weight of expectation must then fall on general Summit commitments, drawn from the more than 120 sovereign nation-states who sent representatives. And yet the tone of their conclusions is maddeningly vague. To wit:

Sexual violence is not a lesser crime: it is an atrocity of the first order and there must be no safe haven for perpetrators anywhere. We were unified in calling for concrete, practical and forward looking outcomes, and sending a message that the era of impunity for wartime sexual violence was over, sending fear into the hearts of would-be perpetrators. Governments are crucial to ending sexual violence, but the Summit drew inspiration and ideas from survivors, activists and artists. We will work with regional and international organisations to ensure that no corner of the globe is left untouched by our campaign.

Concrete, practical and forward-looking. Sounds good. The formalised agreed points of actions are as follows (all points are direct quotes from the chair’s summary):

- addressing impunity requires strengthening accountability and justice in both conflict and post-conflict contexts

- governments should ensure that survivors receive holistic and integrated services that include full sexual reproductive health rights, psycho-social support, livelihoods support and shelter

- Ministers of Defence should take responsibility for preventing sexual violence by their armed forces

- [there is a] need for continued close international cooperation to dismantle the scourge of sexual violence in conflict.

Let us consider these actions in turn. The accountability sections stress the need for improvement and the recognition of thus-far marginalised victims like men and boys. As everyone agrees, an improvement in the level of prosecutions and provision of services demands greater national-level work, not just expanded UN or World Bank budgets. Here there is no pledge of either. Still, by reading between the lines we can see that the Summit may have pushed countries into declarations they would rather not have made. After all, if governments take seriously the recognition of men and boys as survivors of sexual violence deserving of care and restitution (the agreement is for “gender-neutrality”), it will mean that some of them will have to change their laws.

And yet recognition means almost nothing without an explanation of its translation into policy. Countries have duly declared that services should be appropriate to all victims. But how soon will national legal frameworks be expected to conform to international (read: International Criminal Court) norms? No timeline for implementation is given. What kind of services will be created and then cascade? We do not know. The closest we get on local level training is this slightly worrying sentence – “Funding could potentially be leveraged from other donor areas (e.g. Global Fund for HIV/AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria)” – which points towards resources struggles with other development priorities.

The presence of Defence Ministers was important representational politics, and the closing day speech of the Australian Army’s Chief of Staff was some sign of that. Let us briefly leave aside some big questions about how military-to-military training affects gender violence in the field. What does it really mean for militaries to recognise the horror of sexual violence in conflict today? As the agreed document notes, sexual violence is already a war crime (and can be a crime against humanity or constitutive act of genocide). Although historically there have been gaping voids of silence, evasion and complicity, armies have indeed formally been forbidden from using rape as a weapon since roughly the mid-1800s. That states are legally responsible for the conduct of their militaries is therefore not news. Perhaps they will do more to implement those laws, but we cannot yet see how (the United States, for one, recently rejected civilian oversight of justice for military rape).

Promises of greater cooperation should, I think, be taken as axiomatic for any Summit. They may even show one way in which the movement to end sexual violence is being constrained. Many nation-state representatives invoked pre-existing promises, and the need to “do more” to implement long-standing commitments like Resolution 1325. The lack of progress on those commitments tells us something in itself, but endorsing them is also a way of saying that we’ve covered this ground before, and don’t really need to push out in new directions. The content and tenor of the Summit conclusions unsurprisingly reflect that.

And yet the political questions are not quite closed. [2] Professional diplomats would doubtless stress that seeking immediate and large promises from such a diverse group of countries on such a contentious issue – one that does not threaten their immediate national interests or call down much controversy on their governments – is to demand the impossible. Instead, we should look to the way that the energy and attention diffuses through the international system over time. From silence to persistent disruption to mainstreaming within the UN, and then to comprehensive recognition in key states and slowly expanding provision of services in conflict zones. And there might yet be new commitments resulting from the Summit (it is hard to tell, since there does not even appear to be a list of which governments were in attendance).

This gentle progressive narrative diverges starkly from what we all heard last week: the end to business as usual, a veritable revolution in how we think about sexual violence. Not just seeing it as something we can act on, but something that we can eradicate for all time, the way we have with slavery and landmines (Hague’s two favourite comparisons, the semiotics of which deserve a post in themselves). Only in a world where national declarations mirrored true desires should we expect vague speech to lead inexorably to radical transformation. We do not live in that world. Governments have an embarrassment of reasons to move on from this topic and to return to high politics as usual. And this even after they have been cajoled into the room on the basis of confining the topic to rape in war zones.

It is telling that perhaps the most specific commitment delivered during the Summit was Hague’s promise of military support to Nigeria against Boko Haram. The connection of this aid to the plight of women and girls should set the alarm bells of securitisation ringing in many a security scholar ear. Security, like joint humanity, is a performance as much as an action out there. The performances at the Summit, like all public politics, were acts. And as acts, they seem compelling by their very existence. Witnessing them – being the audience for (fearless) speech – is a form of involvement, of public declaration in turn. This kind of politicising, with all of its restrictions and evasions, is not reducible to the question of what concrete institutional policies follow. But without those policies – the banal and granular specificity of which people will be paid to do what, and where – the performance lingers for us, but evaporates for those we speak to, and on behalf of. We wait, still, for the promised ‘action’. Until then the politics of all this will not become what it claims to be: a transformation in foreign policy and a dismantling of wartime gender power. On the evidence of [three weeks ago], the state system is not yet ready for that, and (whisper it) may never be.

[1] For reasons of both space and coherence, I focus here only on the narrow question of the Summit’s success. Crucial wider questions – such as the logic behind the focus on impunity, the character of military rape, the inter-agency dynamics of the humanitarian international, the uses and abuses of celebrity presence, and the possible revival of ethical foreign policy – are deferred.

[2] I leave aside the other projects of the Preventing Sexual Violence Initiative, which might yet make more impact than the Summit. In particular, the International Protocol on the Documentation and Investigation of Sexual Violence in Conflict could act as a valuable resource for many (although there are also those who have said that it only really repackages existing good practice). The experts deployed by the FCO to conflict regions might more quietly enable improved military practices, more suitable services, and higher levels of prosecution.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit Security Watch and browse our resources.