This article was originally published by the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project in May 2016.

As the crisis is Burundi officially enters its second year, the country remains unstable, as dead bodies (often with signs of torture) continue to be discovered throughout various provinces, high-profile assassinations are on the rise, and newly formed armed opposition groups become more active. The conflict has a current reported fatality count of 1,155 between 26 April 2015 and 25 April 2016 (as of the time of publishing); at least 690 of the reported dead (or approximately 60%) are civilians. More than 260,000 people have reportedly fled outside Burundi and thousands have disappeared without trace: approximately 137,000 Burundian refugees have crossed into Tanzania, 77,000 into Rwanda, 23,000 into Uganda, and 22,000 into the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) (UNHCR, 29 April 2016).

Direction

In recent weeks, the crisis has become increasingly wide-spread throughout the country and increasingly varied with respect to actors targeted by violence – ranging from security forces, former soldiers, and members of various opposition groups. The consequences of the past year are stark, but the crisis is not materializing into a civil war, a coup, or any other form of instability that is immediately recognizable. Since June 2015, reports have been referring to President Pierre Nkurunziza’s actions as ‘trigger for civil war’ and ‘spiraling into chaos’, yet continue to use the term ‘political crisis’ rather than ‘civil war’ to describe ongoing events in the country ( Al Jazeera, 28 June 2015).

Because of Burundi’s recent conflict history, some, including the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein, have warned that the ethnic dimensions of the conflict “are flashing red” (The Guardian, 15 January 2016). However, the past year of political violence has remained primarily between regime supporters against regime critics. Additionally, many civilians who have not necessarily supported, or opposed, President Nkurunziza’s leadership or the ruling party National Council for the Defence of Democracy-Forces for the Defence of Democracy (CNDD-FDD) have nevertheless become victims of the conflict by seeking a safer livelihood across borders.

Burundi’s initial riots and protests starting in April 2015 mirror that of other African countries where long-standing presidents have attempted to defy or constitutionally remove term limits. Riots and protests in Burkina Faso in 2014 ousted President Blaise Compaoré within two weeks. In DRC, President Joseph Kabila has been blocked by his legislature from extending term limits. However, riots and protests related to Burundi President Nkurunziza’s announcement of a third term did not as quickly bring a resolution. Instead, Burundi’s unrest has evolved into a seemingly intractable crisis with street clashes between government forces and armed opposition groups, grenade violence targeting police, militia violence against IDPs attempting to flee, and security agents conducting searches and arrests of suspected rebels throughout the country.

The conflict has been characterised by a shutdown of newspapers, raids on radio stations, and freezes on the bank accounts of human rights organisations. Due to the crackdown on media outlets and civil society, news of conflict events and fatalities are often delayed; many events have likely gone unreported. ACLED data often rely on domestic news and local-level sources. ACLED’s Burundi crisis information makes use of crowd-sourced data from the 2015Burundi Project (over a quarter of all events in ACLED’s local-level Burundi dataset rely on such crowd-sourced information, which is professionally monitored and validated), as well as a consolidated network of grass-roots organisations and trained citizen journalists within the country (over half of all events in ACLED’s local-level Burundi dataset draw upon information from this network of grassroots organisations and trained citizen journalists). Figure 8 depicts the difference between the type of events reported by local-level sources versus media outlets; the local-level sources report much of the ‘smaller-scale’ yet chronic issues many Burundians face, namely home searches, (at times arbitrary) arrests, and harassment in border regions while trying to leave or re-enter the country.

Dynamics

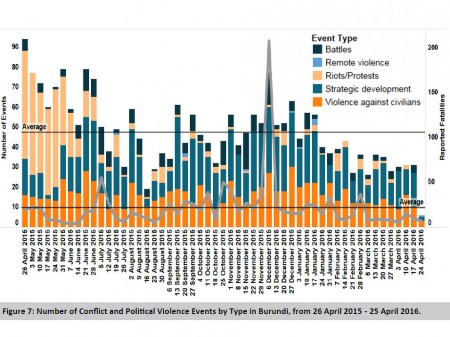

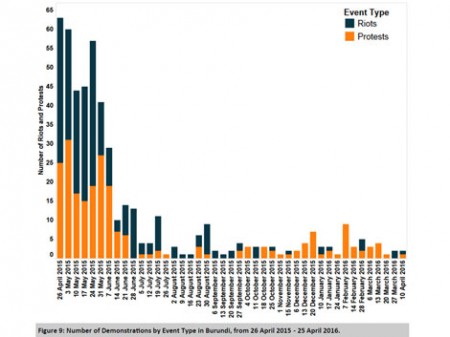

The dynamics of the conflict have stayed largely similar throughout the past year; violence against civilians has consistently comprised almost 75% of conflict in Burundi since last July, although riots & protests made up the majority of events in the early stages of the conflict (April to early June 2015) (see Figure 7). Peaceful protests soon subsided – a function of increased violence against protesters of the regime (see Figure 9). From June to September 2015, violent riots were common. From late 2015, ‘peaceful protests’ have become the primary form of demonstration in Burundi, though these are almost exclusively pro-government protests, over issues including the deployment of AU troops to Burundi, or citing anti-Rwanda and President Kagame rhetoric and chanting. Local reports state that locals are forced to participate in these pro-government protests via threats from police forces and Imbonerakure, a CNDD-FDD youth militia. During protests in March 2016, there were reports that local municipal leaders threatened that anyone who failed to participate would be considered an enemy of the state.

Civilian Targeting

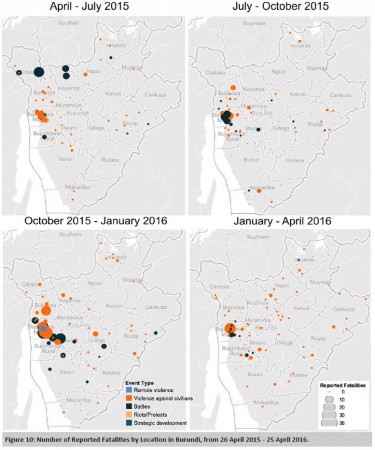

Rates of civilian targeting have increased since the beginning of 2016 and most of the fatalities from this conflict (approximately 60%) have been borne by the civilian population. In the beginning of the crisis, attacks on civilians were more centralized in and around Bujumbura. In more recent periods, these attacks and civilian fatalities are prevalent across the country. Of all reported incidences of violence against civilians in the past year, approximately 49% occurred in provinces outside of the capital areas of Bujumbura Mairie and Bujumbura Rural. Although there is an increasing trend of Imbonerakure beating civilians in Kirundo Provinces bordering Rwanda and in Ruyigi and Makamba Provinces bordering Tanzania, more than 20% of all violence targeting civilians outside of the capital provinces in the past 12 months has occurred in Bubanza, which borders DRC and Lake Tanganyika to the west (see Figure 10). The most commonly targeted civilian victims in Bubanza are either politically affiliated with the ruling CNDD-FDD or affiliated with the opposition group FNL (see Figure 11). In Bubanza, almost half (48%) of all violence against civilians is perpetrated by unidentified armed groups, and one-third of such violence is perpetrated by Imbonerakure.

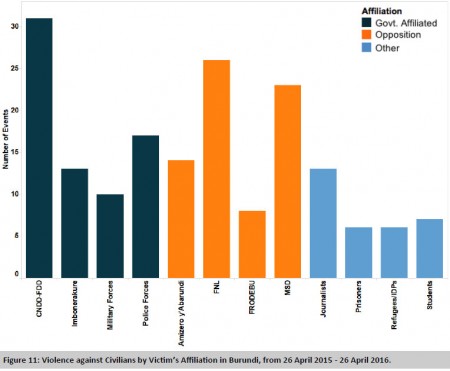

Local reporting indicates that violence against civilians has largely been carried out against opposition supporters and civilians trying to flee violence; this violence is carried out by government forces or affiliates of the government. Where an event includes information on a victim’s identity and their last known whereabouts, the violence can be attributed to a particular group or section of the armed forces. For instance, arrests and subsequent deaths of the same person are widespread; numerous events describe police arresting individuals and taking them to ‘an unknown destination’. Witness accounts are often vague and inconclusive as to whether an individual was detained in a local jail or forcibly abducted. All political-related searches and arrests, whether conducted by various units of the security forces or by unknown armed groups, are coded by ACLED as strategic developments so as not to inaccurately inflate the number of incidences of violence against civilians. However, deaths of those individuals arrested may not be reported and therefore the number of incidents of violence involving police may be higher than what is reported here. In cases where civilian affiliation can be attributed, supporters of the FNL, MSD, and Amizero y’Abarundi have been targeted (13%, 12%, and 7%, respectively, of instances of civilian targeting in which the affiliation of the targeted civilian is known). In incidences where MSD leaders and activists have been targeted (mainly by unidentified armed groups), 74% of such incidences involved at least one fatality.

Yet, there has also been an increased trend of military, police officials, and ruling party CNDD-FDD leaders both targeted by opposition forces (as well as ‘unidentified armed groups’ acting on behalf of opposition forces), as well as targeted by other state forces in cases when individuals are deemed to be critical of the regime. As recently as 20 April 2016, Colonel Emmanuel Buzubona was assassinated in Bujumbura. Although his death is attributed to an unidentified armed group, suspicions lie with government forces. Buzubona had previously been arrested for suspected support of rebel groups during the 11 December 2015 attacks on military barracks. And 25 April 2016, in Bujumbura, unknown attackers used rockets and gunfire to assassinate Brigadier General Athanase Kararuza, a military advisor in the office of the vice president (Reuters, 26 April 2016). This highlights the emphasis being placed on complete support and loyalty to the Burundian regime. In cases where civilian affiliation can be attributed, CNDD-FDD members, as well as members of the police and military forces, have been targeted (16%, 9%, and 5%, respectively, of instances of civilian targeting in which the affiliation of the targeted civilian is known).

Battles

While battles made up about a quarter of events between July and December 2015, these events have become less common. These battles largely consist of state forces, such as police or military forces, taking up arms against unidentified armed groups, which are believed to often consist of opposition supporters. However, with the crack-down of police searches of homes for weapons and opposition supporters, coupled with the increased targeting of civilians, it has become increasingly difficult for opposition supporters to continue taking up arms against the state, and to be open about their acts against the state. This is partially why a high proportion of acts involve ‘unidentified armed groups’. Battles involving unidentified armed groups are often described as involving ‘opposition forces’ or ‘insurgents’; therefore, it is difficult to attribute violence to just one of the numerous opposition groups active in the country.

There are a number of ‘acts of provocation’ in this conflict, similar to previous Burundian conflicts. In November 2015, unknown assailants launched two mortar shells at the presidential palace, but caused no damage. Targeting the palace may seem reminiscent of attacks that sparked the country’s civil war. Tutsi paratroopers assassinated Burundi’s first Hutu president Melichor Ndadaye in October 1993, sparking an ethnic-based war that claimed 300,000 lives.

The deadliest day of the political crisis occurred on 11 December 2015, when armed groups carried out coordinated attacks on military sites in Ngagara, Musaga, and Mujejuru. At least 87 were reportedly killed and 49 were captured. Police retaliated with searches, raids, and arrests throughout Bujumbura. Dozens of civilians’ bodies were discovered in mass graves in the days and weeks afterwards. However, mass graves may not only be a tactic of government forces. On 29 February 2016, members of press were allowed to view a mass grave in the predominantly anti-government neighborhood of Mutakura. Bujumbura Mayor Freddy Mbonimpa stated that the victims were supporters of a third term (Bloomberg, 1 March 2016).

The events of 11 December 2015 garnered attention from international organisations, with the United Nations (UN) Human Rights Council unanimously backing an investigation into the country’s crisis. The African Union (AU) approved the deployment of a 5,000-strong African Prevention and Protection Mission in Burundi (MAPROBU), which has yet to be deployed due to opposition from the Burundi Government. In February 2016, the government agreed to allow 100 military observers and 100 human rights observers into the country. Promised action by the AU, often-postponed peace talks mediated by Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni, and a visit from UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon and a delegation of African leaders in late February have had no tangible effect on the number of conflict events. Due to continued reports of acts of killing, torture, imprisonment, sexual violence, and enforced disappearances, International Criminal Court Prosecutor Fatou Bensouda announced on 25 April 2016 the start of a preliminary investigation into the situation in Burundi (International Criminal Court, 25 April 2016).

Clionadh Raleigh is Professor Of Human Geography at the University of Sussex

Dr. Roudabeh Kishi is a Post-Doctoral Research Fellow with ACLED at the University of Sussex.

Janet McKnight is a New Orleans-based attorney and ACLED Africa Coder focusing on political violence in Sudan and South Sudan.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit CSS Security Watch Series or browse our Digital Library.

2 replies on “Burundi Crisis Year One”

Thanks for sharing, our “somewhat” elected leaders lack the abstract intelligence to do what’s right for their people. So this drama continues to play on with wars, ethnic cleansing, corruption, religion, poor infrastructure, constitution change, race and so on. Excuses galore! Africans it’s time to place value on your fellow human beings and drop the excuses otherwise in 50 years time we’ll still be having this conversation.

This is the order of the day in most developing countries power struggle and corruption. Solution for such scenarios is the term limits. Constitutions should be amended so that presidents have terms limits so that they don’t stay forever or assume that they are their to stay.