This article was originally published by Political Violence @ a Glance on 22 July 2019.

In 2018, the global measles outbreak claimed 109,000 lives and sickened 200,000 more across 126 countries. And the outbreak does not appear to be abating. Outbreaks in Europe and the US have been traced to Ukraine, where the spread of measles is generally attributed to an ongoing civil war. But the specific mechanisms connecting civil war and disease outbreak are unclear in this case.

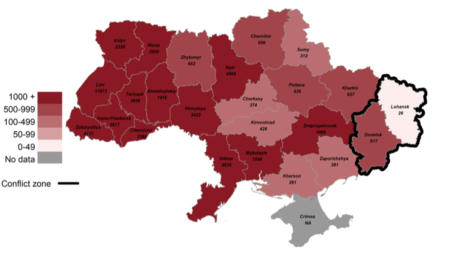

Here’s the puzzle: the conflict in Ukraine is concentrated in the eastern part of the country, where the government has been fighting Russian-backed separatists since 2014. And while there is certainly a higher-than-normal incidence of measles in regions near the fighting, such as Donetsk and Luhansk, the most severe outbreaks are in western Ukraine.

If the Ukrainian civil war explains the country’s measles outbreak, why is the fighting in the easternmost part of the country, while the most severe outbreaks are in the west?

Despite this puzzling geography, we suspect that the conventional wisdom linking civil war and disease outbreak is correct in this case. Consistent with Cullen Hendrix’s post from last year, our own birds-eye view of the data suggests that between 2012 and 2017, countries with ongoing civil war experienced 170 more cases of measles per year than countries without civil war (controlling for population and GDP per capita). But what exactly is the nature of the link? And, in particular, how can we explain the distribution of measles outbreaks in Ukraine?

We can think of four possible answers:

- 1 Internally-displaced persons (IDPs), but…. The interruption of regular health care in the conflict zone, combined with internal displacement from east to west, could have hastened the westward spread of measles in Ukraine. If IDPs are the answer, though, the connection is not straightforward. Most Ukrainian IDPs have stayed in the east – they have just moved from cities like Bakhmutska and Kramatorska to other nearby areas such as Kharkiv. But a closer look at the demographics of IDPs sheds light on the geography of the outbreak. Compared to the east, children comprise more than double the relative proportion of IDPs that have been internally displaced to the west. The conflict has put enormous pressure on Ukrainian vaccination efforts, with at one point only 42% of children receiving the necessary doses. Because children are most vulnerable to measles, interruption of vaccinations in the east, coupled with the westward movement of families, likely helps explain the apparently puzzling locations of various outbreaks. Our back-of-the-napkin data analysis suggests that a 1% increase in the proportion of children among the overall IDP population corresponds to an approximately 6% to 30% increase in the incidence of measles within a province (controlling for population, local measures of wealth, and conflict intensity).

- 2 Weakened health infrastructure. Civil wars are often enabled by, and certainly cause, erosion of public institutions, including those relating to public health. Liberia had 237 physicians in country in 1989 when civil war broke out, 89 by 1998, and fewer than 20 in 2003. Partly as a result of the outbreak of conflict in 2014, Ukraine was late to order vaccines in 2014/15. In 2016, less than half of Ukrainian infants received their initial vaccination and less than a third of toddlers received their follow-up shot as a consequence.

- 3 Erosion of trust. Conflict has been shown to erode trust on a number of dimensions. Among these may be trust in health care. The CIA infamously used a polio vaccine scheme in its hunt for Osama bin Laden; one consequence was subsequent – and sometimes violent – resistance to future vaccinations, including a number of attacks against health workers. In other research, one of us has found that areas in Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone experiencing the highest rates of past wartime violence were also the areas where the 2015 Ebola outbreak was most severe, possibly because of erosion of trust in health workers. We observe a similar dynamic in eastern DRC’s Ebola outbreak today. And in 2008, the death of a Ukrainian teenager after (but not because of) receiving the measles vaccine fueled national distrust, which is also in evidence in Europe more broadly.

- 4 Missing data. It is possible that this puzzle is not, in fact, a puzzle. Perhaps the heat map is incorrect because it is very difficult to obtain good data on health outcomes from conflict zones. This problem is compounded by a brain drain of local health workers and the reluctance of INGOs like MSF and ICRC to endanger their own personnel in an era of increasing attacks against aid workers. The Ukrainian Red Cross Society, whose data we used to produce the heat map above, as well as other aid organizations like the World Health Organization, face complicated security that limit their ability to collect reliable data in conflict zones. What is more, states experiencing disease outbreaks have multiple incentives to underreport the incidence of disease, ranging from concerns about tourism to the potential for negative economic consequences.

We can say with confidence that there is a correlation between civil war and infectious disease. But we cannot yet say why. In an era of globalized transport and quickly-evolving microbes that do not require passports, however, it is critical to uncover these missing links. Even in rich countries like the US, outbreaks place significant burdens on local public health department budgets and can encourage public officials to implement aggressive policies such as banning unvaccinated children from public spaces and local schools. In areas with weaker public health infrastructure, fears of the disease have increased demand for the vaccine, resulting in shortages.

We also know that measles is a highly preventable disease. Of the many challenges associated with civil war we can anticipate, this one may be among the most solvable. But the lack of a strong international regime to protect IDPs presents a critical obstacle. Nonetheless, the consequences of outbreaks and the ubiquitous and fast connections between distant places underscore the need to understand–and mitigate–the drivers and mechanisms between disease and war.

About the Authors

Tanisha M. Fazal is an Associate Professor of Political Science at the University of Minnesota and a regular contributor at PV@Glance.

Logan Stundal is a PhD student in the Department of Political Science at the University of Minnesota.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS website.