This article was originally published by the NATO Defense College (NDC) in January 2020.

The credibility of any alliance depends on its ability to deliver deterrence and defence for the safety and security of its members. Without capability, any alliance is deprived of credibility and exists only on paper. Despite a rocky history – up to and including the current debate on burden-sharing – capability lies at the heart of NATO’s success. There is good cause to draw optimism from the Alliance’s accomplishments throughout its 70 years in providing a framework for developing effective and interoperable capabilities.

However, the future promises serious challenges for NATO’s capabilities, driven primarily by new and disruptive technology offering both opportunities and threats in defence applications. Moreover, developments in these areas are, in some cases, being led by potential adversaries, while also simultaneously moving at a pace that requires a constant effort to adapt on the part of the Alliance. On the occasion of NATO’s 70th anniversary, the future outlook requires a serious conversation about NATO’s adaptability to embrace transformation and develop an agile footing to ensure its future relevance.

The Value of Capability: Historic Perspectives

Having the right set of capabilities is a foundational element of the Alliance. The North Atlantic Treaty enshrines the impetus to develop and maintain military capability in its article 3: “in order more effectively to achieve the objectives of this Treaty, the Parties, separately and jointly, by means of continuous and effective self-help and mutual aid, will maintain and develop their individual and collective capacity to resist armed attack”.

NATO’s efforts in support of these ends are similarly long standing. Through nearly the entirety of its history, the Alliance has provided a framework of tools and resources to encourage the development of interoperable and combat-capable forces. The establishment of NATO’s integrated military structure in 1951 is, in fact, predated by the stand-up of the Military Agency for Standardization (1950), known today as the NATO Standardization Office, which is a repository of hundreds of NATO standards in use by Allies and many other nations.

Moreover, capabilities have long served as material manifestations of the Alliance’s transatlantic bond. North American and European investments in research and development, multinational acquisition, and collective infrastructure not only deliver operational capabilities while benefitting from economies of scale, but also serve as measurable and tangible commitments to the Alliance’s shared defence and security.

The Contemporary Context: Cause for Optimism

Despite some energetic debates on Alliance defence spending, burden-sharing, and readiness, the present status and outlook of the Alliance’s capabilities offer cause for optimism. While the situation is not perfect, Allies are making serious and measurable investment in their capabilities, and NATO is continuing to provide the frameworks and encouragement to facilitate collective progress.

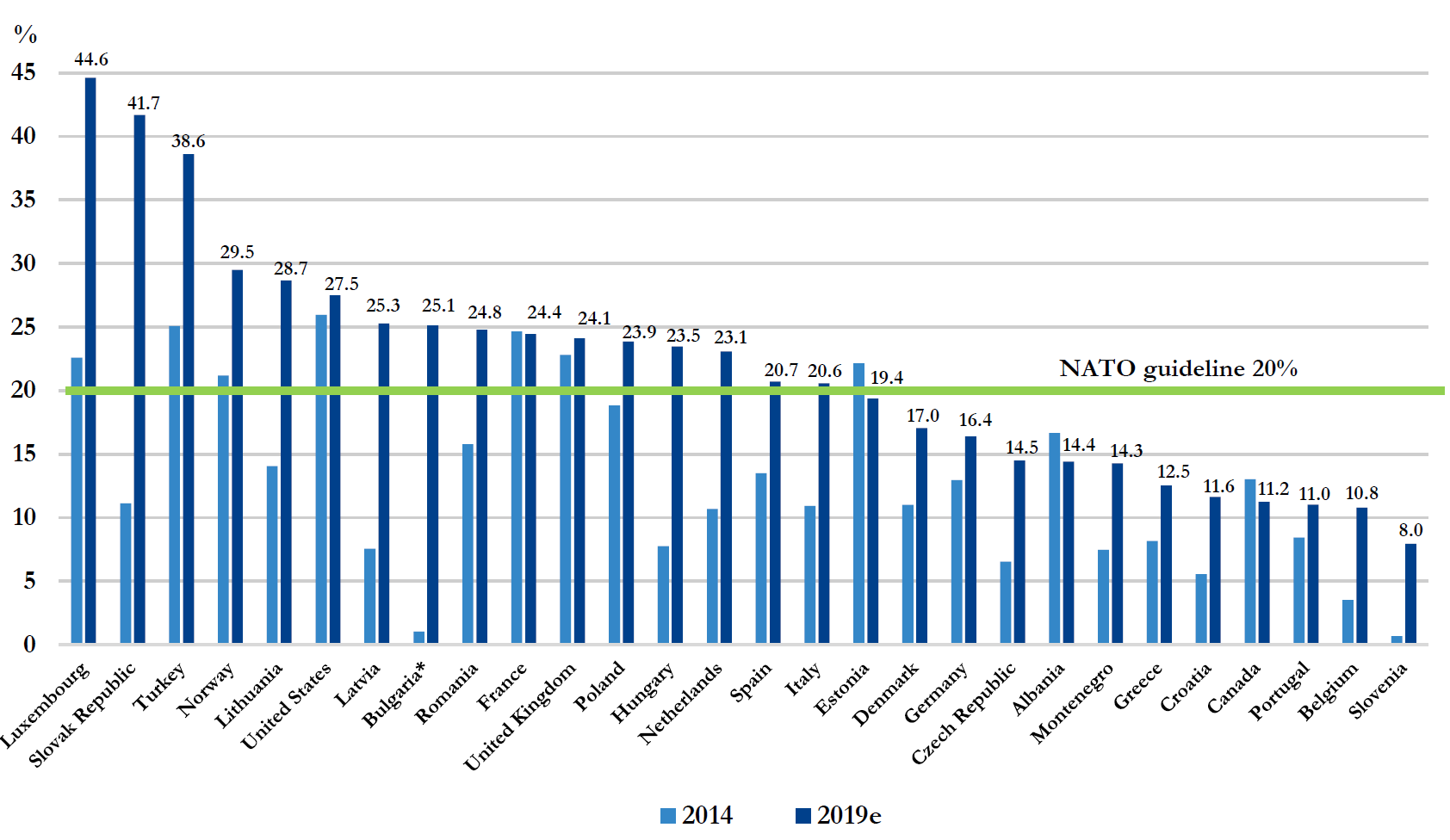

On the national efforts, the progress of Allies in reaching the NATO guideline of 2 percent of defence expenditure as a share of their Gross Domestic Product has been well documented. From 2016 to 2020, European Allies and Canada will have spent an additional USD130 billion, with more and more Allies meeting or having developed plans to meet the 2 percent target by 2024. Less documented is the swift and significant uptick in national equipment expenditure as a share of defence expenditure, for which NATO has established a guideline of 20 percent. Figure 1 shows that since 2014 nearly all Allies have reported increased expenditure, many have doubled or even tripled their expenditure, and more than half have already met the 20 percent guideline. In concrete terms, this means Allies are dedicating more of their resources towards researching, developing, and acquiring new capabilities.

NATO, for its part, continues to help Allies to find value for the money they invest in capabilities. The primary example is the facilitation of multinational cooperation. This in itself is not a new development. NATO established the Conference of National Armaments Directors in 1966, with the intent of providing a common forum for Allies to identify and pursue opportunities for cooperation in capability development. Multinational cooperation has been known by many names in NATO circles over the years, including as the ‘Smart Defence’ initiative, but the benefit has fundamentally remained the same: working together drives down perunit costs through economies of scale, supports better coherence and prioritisation in how Allies allocate their resources, and allows Allies to achieve more together than they would otherwise on their own.

Multinational cooperation under NATO is not simply a paperwork exercise. Through it, Allies are delivering tangible capabilities, and the outlook is positive. Among the higher visibility projects agreed at the level of their Defence Ministers, Allies – in various groupings and configurations – are currently participating in ten separate efforts, ranging from the bulk purchase of munitions to the establishment of a training centre for air crews operating in support of special forces or work on maritime unmanned systems. Allies continue to both launch new projects and join existing ones at a steady pace, with new commitments made at nearly every NATO Defence Ministers’ meeting. In short, cooperative capability development through NATO is a reality and helps to address NATO’s capability shortfall.

There is also cause for optimism for capabilities developed between NATO and its international partners, primarily the European Union. Here, the current template for successful cooperation is still the Multinational Multi-Role Tanker Transport Fleet. Initiated by a NATO Capability shortfall assessment, this project started with the European Defence Agency work on requirements, while the acquisition is managed by the Organisation Conjointe de Coopération en matière d’Armement as contract executing agent for the NATO Support and Procurement Agency, who will in turn manage the life cycle of the fleet. The resulting capability operated by the European Air Transport Command will significantly contribute towards the air-to-air refueling requirements of both NATO and European nations.

Provided they avoid unnecessary duplication and are well coordinated with NATO priorities, European initiatives related to capabilities can contribute to fairer burden-sharing by Europe and can lead to capabilities that should ultimately be made available to support NATO’s own operations and activities. In other words, European capabilities are NATO capabilities.

Figure 1: Equipment expenditure as a share of defence expenditure (%) based on 2015 prices and exchange rates

The Future Outlook: Meeting the Challenges of the 21st Century

The Alliance’s 70 years have endured seismic shifts not only in the geopolitical context, but also in the technologies that underpin and constitute its capabilities. From this perspective, NATO is no stranger to change; the last 70 years saw remarkable transformations ranging from the birth of the transistor, to the creation of the internet, to the invention of the smartphone. However, the accelerating pace of this change is challenging for NATO’s future capabilities, and calls for a serious discussion about the Alliance’s agility and adaptability to retain its technological edge.

Implications for the Alliance

The Alliance’s use and leadership in sophisticated high-end technology has underpinned its successes in both peace and conflict. The current outlook places the Alliance’s success at risk for two reasons: broadened accessibility by peer and non-state competitors, and the pace of change. Put simply, rapid changes in the spaces of both threats and opportunities will drive disruptions in how NATO develops and uses capabilities. “Business as usual” may no longer be sufficient to ensure the Alliance’s competitive advantages.

Firstly, broadening accessibility to technology has shattered the near-monopoly on technological advantages enjoyed by Allies up to now. Furthermore, NATO’s potential adversaries are not only investing in disruptive technologies; they are – in some cases – directly leading developments and working to close the gap with NATO nations in others.

For example, China has emerged as a major competitor for the future capability space. Chinese telecom companies are already pursuing the roll-out of 5G infrastructure in many nations; with massive investment in research and development. Moreover, China has demonstrated real-world applications of quantum technology while also maneuvering to gain an edge in quantum research and development, with EUR9 billion recently committed to develop a national quantum laboratory. NATO Allies will struggle to bring individually a similar magnitude of resources to bear towards research and development in these areas.

Secondly, the pace of change has accelerated at a tempo that risks outpacing our ability to exploit and, as necessary, counter the technological advancements on the horizon. Many of these technologies are driving towards faster and more distributed decision-making, which in turn bumps up against the sometimes bureaucratic and conservative nature of NATO’s machinery and decision making. Posturing the Alliance to fully embrace these technologies will require an adapted mindset and culture of delegating authority and accepting ambiguity.

One case for improvement is in the area of NATO processes, particularly those that manage procurements, standardization, and capability life cycles. We often strive for perfection in our future requirements, and engineer our processes around numerous decision gates and complicated management structures. The result is a capability that can be over budget, late, and obsolete when delivered. NATO has taken some healthy steps in this direction with the adoption of a new model for governing common funded capabilities with fewer decisions and streamlined oversight. But continued efforts are needed.

Industry also has a substantial role to play in this area. Our traditional defence industrial base should not be complacent with a business model that can be slow, cumbersome, and risk averse. In what Klaus Schwab has defined as the “fourth Industrial Revolution”, the changes on the horizon “herald the transformation of entire systems of production, management, and governance”1 while entirely upending existing industrial value chains. The success of Allies’ industries will depend on more acceptance of risk, greater investment in research and development, and an adapted mindset towards partnering with players outside the traditional defence sphere.

Blueprints for the future?

The future outlook for disruptive technology is not entirely negative. Two new initiatives show exceptional promise to invert traditional capability development models, while seizing upon the opportunities offered by new technology. They demonstrate vividly how NATO adapts.

The first is the Maritime Unmanned Systems Initiative. Here, 14 Allies have committed to a cooperative framework for developing and integrating unmanned systems into NATO’s defence architecture.2 The project is aimed at bringing autonomy and unmanned capability to bear in support of tedious and dangerous jobs at sea, including anti-submarine and counter-mine warfare. Beyond leveraging new technology, the project is also leveraging a “start up” mindset for agility and lean approaches. The project has benefited from experience drawn from industry, academia, and government, including Coca Cola and the Pentagon’s Defense Innovation Unit. This model has already paid dividends: less than a year after the first commitment was taken, the largest-ever exercise of NATO unmanned underwater, surface and air vehicles took place off Portugal.3

The second initiative is the Alliance Future Surveillance and Control capability. In a novel example of obsolescence management, NATO leaders have committed to cooperate towards defining a replacement for NATO’s AWACS fleet in anticipation of its retirement around 2035. The project launched in 2016 with a fundamental re-evaluation of NATO’s future needs, eschewing any assumptions that AWACS would simply undergo a “like-for- like” replacement. The project has since arrived at capability requirements that drive for an integration of surveillance and C2 across multiple domains. Allied industries have now been challenged to offer ideas on how NATO’s requirements could be fulfilled by 2035. Up to six concepts are being sought in order to encourage a wide variety of innovative solutions, including those that leverage emerging and disruptive technologies.

Both of these projects are in their early steps. Nevertheless, their models are contesting the traditional approaches to defence acquisition by embracing disruptive technology, tapping into industry expertise, and leaving space for future capability growth. These projects offer promise for the future adaptability and agility of NATO capability development, and as such deserve close attention and support.

Conclusion: Maintain NATO’s Lead in an Uncertain Future

The Alliance has over the last few years weathered a vigorous debate on burden-sharing. Allied spending on capabilities is increasing dramatically. A growing number of Allies are teaming up under the banner of multinational cooperation to drive down costs and achieve more than the sum of their parts. Finally, European nations are also taking greater strides towards resourcing development of their own capabilities.

Looking forward, the landscape offers serious challenges. While change in technology is nothing new in NATO’s 70 year history, the challenge stems from both the speed of this change coupled with the loss of NATO’s quasi dominance on many high-end technologies. The emerging areas touched upon here – to include quantum technology, “big data” analytics and artificial intelligence, and 5G cellular technology – all offer profound opportunities and potential threats for NATO’s future capabilities.

The challenge is not insurmountable, and the latest NATO initiatives related to innovation and future capabilities demonstrate the organization’s continued ability to change 70 years into its history. The success of these projects – and of NATO’s capability portfolio more broadly – will depend upon the willingness of the Alliance and its industrial base to take risks, be agile, and innovate. Within the Alliance’s overall adaptation agenda, rethinking our approaches and mindsets to capability development will be essential to maintain NATO’s lead in an uncertain future.

The NATO Defense College applies the Creative Common Licence “Attribution-Non Commercial-NoDerivs” (CC BY-NC-ND)

Notes

1 K. Schwab, “The fourth Industrial Revolution: what it means and how to respond”, Foreign Affairs, 12 December 2015.

2 Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Spain, Turkey, the United Kingdom and the United States.

3 Recognized Environmental Picture, Maritime Unmanned Systems 2019 – known as REPMUS19.

About the Authors

Camille Grand is NATO’s Assistant Secretary General for Defence Investment.

Matthew Gillis is Defence Investment Staff Officer at NATO HQ.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS website.