The Roman Catholic Church is one of the oldest religious institutions in existence, with more than a billion members, in almost every country of the world. With the election of Pope Francis, it is timely to ask: how does the Roman Catholic Church enter into dialogue with the world? How the Catholic Church uses dialogue to deal with differences is not only significant for its members, but also for inter-religious and world peace. The Abbot of Glenstal Abbey, Mark Patrick Hederman, has some intriguing answers to this question. Two points from his recent book “Dancing with Dinosaurs” are summarized below:

Why do we need religious institutions?

We have to understand the nature of large institutions – be these multinational companies, the United Nations or the Roman Catholic Church – if we are to avoid harming others and ourselves. Seeking to change them rapidly, to revolutionize them, is a recipe for failure. Their very size and cumbersome plodding through the course of history is their guarantee of sustainability. In Hederman’s words: “Unless any organization becomes a dinosaur it will not survive the vicissitudes of history.” But why do religions need such institutional structures? Ultimate truth can never be grasped or controlled by any earthly institution. It can never be truly described in words. As Hederman says: “Our culture has been built on a lie and Christianity has helped to promote and sustain that lie. And the lie is this: that it is possible to work out in our heads a logical system which will give us access to ultimate truth.”

If ultimate truth is more to be touched by the heart (e.g., the church of St John) than grasped by the head (e.g., the institutional church of St Peter), why do we still need the institutional church? Despite its limitations, Hederman argues that the institutional church can support us in entering into a living, mystical relationship with God. Music notes are not the same as living music, and the institutional structures are not the same as a living relationship with God, but they can help. For some people, the institution stands in the way and they are better off without it, but for others it can be an aid, and therefore it is needed. And, more importantly according to Hederman, without some existing container which stands visibly in the world, however improbably, there is every likelihood that ultimate truth will be forgotten about altogether.

What is the Catholic Church’s mandate for dialogue?

If we need large institutions, we need to understand their internal decision-making processes, as this is the basis of how they relate to others. Within the Catholic Church, there are two main camps that have shaped the internal decision-making process. The first camp of conservatives defends a “no change” policy, based on understanding the truth in terms of constants contained in the scriptures and tradition. The second camp of progressives sees the truth of the Church in relation to its historical context. They argue that we are shaped by time and are walking into an unknown future, so that the Church has to negotiate, develop and change. Any compromise of the Catholic Church is a result of these two opposing worldviews.

In relation to dialogue with others, the Second Vatican Council (1962-1965, involving 7500 people from 116 different countries) exemplifies how such compromises can be reached. One of the key compromises entailed changing the word “is” (est) to “subsists in” (subsistit): instead of stating that the Church of Christ is the Catholic Church, the new formulation stated that the Church of Christ subsists in the Catholic Church. This piece of creative ambiguity allowed the conservatives to hold that the new formulation is but a paraphrase of the previous version, while it allowed the progressives to claim a step forward in recognizing the validity of other churches and religious communities – therefore opening the door for dialogue. The Second Vatican Council stated that: “Nevertheless, many elements of sanctification and truth are found outside its (i.e. the Catholic Church’s) visible confines.” (Lumen Gentium 8, brackets added). Dialogue with the other was no longer a one-way road of converting the other to the one true Catholic Church; dialogue became a two-way path where both partners could be enriched and made more “whole” in their understanding of the world and God. Since the Second Vatican Council, the Pope and all Catholics have a clearer mandate to dialogue with the world outside their own community.

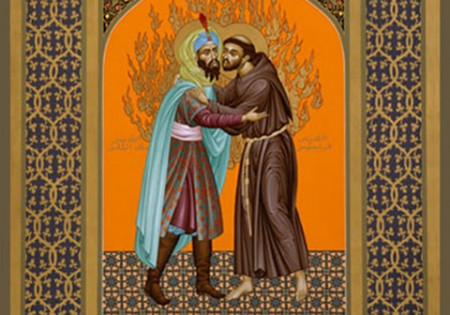

Moving from Hederman’s book to the situation today, the following points indicate how Pope Francis may live the Catholic mandate for dialogue. In 2011, then-Cardinal Bergoglio wrote: “Dialogue is born from an attitude of respect for the other person, from a conviction that the other person has something good to say. It assumes that there is room in the heart for the person’s point of view, opinion, and proposal. To dialogue entails a cordial reception, not a prior condemnation. In order to dialogue it is necessary to know how to lower the defenses, open the doors of the house, and offer human warmth”. The chosen name of Francis is also a sign that the new pope may try to follow the footsteps of Francis of Assisi, who used dialogue with the Sultan al-Malik al-Kamil during the fifth crusade, seeking peace between Muslims and Christians.

The Catholic Church has a mandate to dialogue with others, and there is hope for how Pope Francis will live this dialogue. Yet due to the necessary dinosaur nature of the institutional church, dialogue between Catholics and the world outside of Catholicism will be slow, and calls for great patience and perseverance.

Simon J. A. Mason is a senior researcher and head of the Mediation Support Team at the Center for Security Studies (CSS).

“Mediation Perspectives” is a periodic blog entry provided by the CSS’ Mediation Support Team. Each entry is designed to highlight the utility of mediation approaches in dealing with violent political conflicts.

For additional reading on this topic please see:

Patriarch Kirill’s Visit to Poland

Bosnia’s Dangerous Tango: Islam and Nationalism

Tunisia: Secular Social Movements Confront Radical Temptations

For more information on issues and events that shape our world please visit the ISN’s featured editorial content and Security Watch.