Image courtesy of World Economic Forum/Flickr. (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Image courtesy of World Economic Forum/Flickr. (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

This article was originally published by Political Violence at a Glance on 30 April 2020.

In 2013, during the 50th anniversary of the Organization of African Unity (now known as the African Union), African leaders solemnly declared their aim to “silence the guns” in Africa by the end of 2020. Consequently, silencing the guns—ending armed conflict—is the African Union’s theme for 2020, with high-level discussions on how to implement this goal throughout the year.

On the face of it, “silencing the guns” seems unrealistic, even naïve, given intense, protracted armed conflicts in Mali, Libya, Nigeria, South Sudan, Somalia, and the Central African Republic. But the campaign is not really about ending all armed conflict in Africa. It is about signaling that the African Union and its member states are fully committed to preventing and resolving armed conflict in Africa as best they can.

Africa’s leaders know the difficulty of the task and are in the best position to reduce armed violence on the continent. Mediation is a key mechanism for doing so, but who does it best?

Recent research comparing the effectiveness of African and non-African mediation efforts in armed conflicts in Africa between 1960 and 2017, shows that African third parties outperform their non-African counterparts. African mediation efforts are more likely to lead to peace agreements, and the agreements are more likely to be durable.

This is a rather puzzling finding. In the bulk of academic research, African mediators are viewed as unsuccessful because of their limited capacity to coerce or induce the conflict parties to make peace. For instance, Smock and Crocker argue that, due to the severely limited financial capabilities of African actors, African peacemaking efforts on their own have little chance of success. Even proximity to the adversaries and deeper knowledge of the conflicts is not generally thought to be an effective substitute for the diplomatic and political tools external mediators are thought to possess.

Writing about his study of civil conflict in East Africa, Khadiagala claims that, “by intervening with only limited tangible and material resources, African interveners have contributed to the widespread perception of being meddlers rather than mediators.” Møller takes it even further, saying that: “it would be surprising if the world’s poorest continent were able to solve the world’s most frequent and widespread as well as most deadly conflicts.” These claims about the effectiveness of African mediation are in line with the mediation literature writ large, which tends to equate the capacity of third-party mediators with their ability to coerce and induce.

Despite the academic bias against African mediators, the evidence shows that they outperform their counterparts. And the main reason why is that they have something external mediators lack: legitimacy. African mediation relies heavily on moral persuasion predicated on shared values. Legitimacy is derived from those values—specifically as they relate to two sets of norms: a widely shared commitment to sovereignty and African unity, and to anti-imperialism and anti-neocolonialism. Taken together, these norms explain the pan-African commitment to African solutions to African conflicts, and the preference for African actors to mediate African conflicts.

Given that mediation is a voluntary process in which the conflict parties have to consent to the involvement of the third party and the final outcome, it is surprising that most studies on international mediation ignore the role of legitimacy.

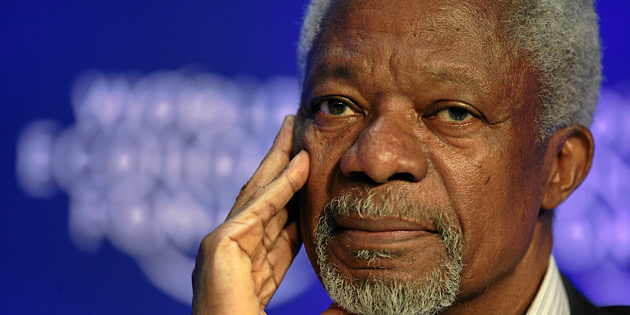

Legitimacy and gravitas are what enabled the African Union mediation effort, led by Kofi Annan, to achieve swift and durable results to resolving Kenya’s post-2007 electoral crisis. Kofi Annan “possessed no authority to promise aid or threaten sanctions against the intransigent parties, nor did he have better access to information about the capabilities and resolve of the respective parties than they had themselves.” But Anan did possess a high degree of third-party legitimacy—and he made full use of it. Moreover, African leaders helped to strengthen his legitimacy by publicly declaring that peace in Kenya was not only important for Kenya, but for all of Africa. The President of the African Union at the time, Alpha Oumar Konaré, publicly expressed that “If Kenya burns there will be no tomorrow.” When the African Union mediation team arrived in Nairobi to mediate, they told the conflict parties that they had discussed the conflict with Nelson Mandela and that he sent his best wishes and sought to remind them that all of Africa was watching the peace process. Less than a month later, the conflict parties signed an agreement, which was the basis for the Grand Coalition Government that successfully mitigated the conflict.

Silencing the guns in Africa is not merely pan-African rhetoric. The African Union’s declaration in 2013 — “reaffirming our commitment to the ideals of Pan-Africanism and Africa’s aspiration for greater unity,” a “strong commitment to accelerate the African Renaissance by ensuring the integration of principles of Pan Africanism in all our policies and initiatives,” and goal to “push forward the agenda of conflict preventing and peacemaking through the African Peace and Security Architecture” — all serve to strengthen the legitimacy of African mediation efforts. It also makes it much harder for African leaders of countries at war to play the sovereignty card and reject African mediation.

For instance, former Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir accepted mediation by the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD) in 1994, even though he had repeatedly expressed his commitment to destroy the southern rebel movement. Commenting on the mediation effort, al-Bashir said: “Africans have become mature enough to resolve their own problems and are no longer in need of a foreign guardian.” The mediation effort by IGAD, he said, would be “without loopholes through which colonialism can penetrate on the pretext of humanitarianism.” Indeed, external observers noted that although “both the Sudanese government and the southern insurgents … have good tactical reasons not to negotiate, they have faithfully turned up at IGAD negotiating sessions because of Organization of African Unity peer pressure.”

It would take until 2005 before the Sudanese government and the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement/Army (SPLM/A) finally reached a negotiated settlement to end the war. US pressure also helped to move conflict parties towards compromise, but it was the legitimacy of African-led mediation that allowed the process to continue and eventually coax the conflict parties towards compromise.

On 4 January 2011, five days prior to the start of the referendum on southern Sudan’s independence, former South African President Thabo Mbeki, who was tasked by the African Union to oversee the implementation of the agreement between the Sudanese government and the SPLM/A, gave a speech in Juba. In this speech, he told the crowd: “We have come among you not as foreigners, but as fellow Africans who are convinced that we share a common destiny. Accordingly, it is not possible for us to distance ourselves from the problems this sister country and people face, arguing that these are Sudanese problems. To us, the problems of Sudan are our problems, its challenges and successes our challenges and successes.”

A high degree of legitimacy is not a panacea of course. Resolving violent conflict is enormously difficult, and even third parties that are legitimate in the eyes of the conflict parties will struggle to make peace. But African third parties’ high degree of legitimacy is better able to pull conflict parties towards signing an agreement that lasts. The legitimacy of African third-party mediators is therefore ultimately more important, more valuable, and more effective for resolving conflict, than the vast sums of money and the military capabilities non-African third parties can bring to bear.

About the Author

Allard Duursma is a Senior Researcher in Peace Processes at the Center for Security Studies at ETH Zurich. @AllardDuursma

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS website.