This article was originally published by the Institute for Security Studies (ISS Africa) on 4 February 2016.

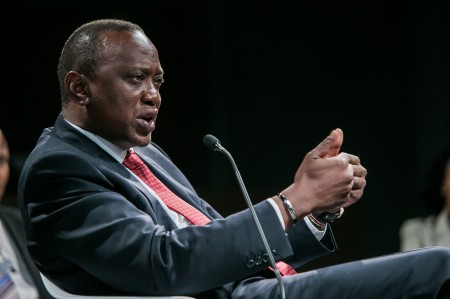

As the 26th ordinary summit of the African Union (AU) ended in Addis Ababa on Sunday, Kenyan media led with reports that ‘the African Union has adopted, without amendments, a proposal by President Uhuru Kenyatta to develop a roadmap for withdrawal from the Rome Statute’ – as the Daily Nation put it.

What had actually unfolded was a little more nuanced. The AU heads of state did not decide to withdraw from the International Criminal Court (ICC) en masse – yet. Nor even did Kenyatta ask for that. In his speech to the AU Assembly, he asked the summit to give the Open-Ended Committee of African Ministers on the ICC ‘a new mandate to develop a roadmap for withdrawal from the Rome Statute as necessary.’

The key phrase here is ‘as necessary.’ The rest of his speech makes clear that withdrawal from the ICC would be conditional on the court failing to meet the AU’s demands. As Kenyatta said earlier in his speech: ‘It is my sincere hope that our ICC reform agenda will succeed so that we can return to the instrument we signed up for. If it does not, I believe its utility for this continent at this moment of global turmoil will be extremely limited. In that eventuality, we will be failing in our duty if we continue to shore up a dysfunction(-al) instrument.’