Mediation Perspectives is a periodic blog entry that’s provided by the CSS’ Mediation Support Team and occasional guest authors. Each entry is designed to highlight the utility of mediation approaches in dealing with violent political conflicts. To keep up to date with the Mediation Support Team, you can sign up to their newsletter here.

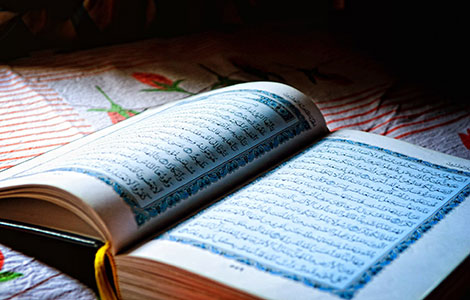

The fourth instalment of the CSS Mediation Perspectives Blog Mini-Series on the use of religious resources in peace mediation (Part one: Criteria, Part two: Christianity, Part three: Buddhism) comes from a Muslim perspective and looks at how peace, conflict and mediation are part of Islam.

Religions promote peace and provide moral guidance and legal injunctions to restrict and moderate the use of violence. Followers of a religion can comply with these guidelines or transgress against them as such followers are neither angels nor devils. Instead, they are human beings with all the complex aspirations to peace and temptations to violence that the human condition entails. In that respect, Islam is no exception.

Peace occupies a central position in Islam and is viewed as being three dimensional: with God, with the self and with others. In the Islamic normative framework, peace must inform the attitude and the behaviour of every Muslim: “The true Muslim is the one with whom others feel in peace and do not fear his/her tongue and hand” (Prophet Muhammad). There is a whole symbolic framework of peace in Islamic religious language. For instance, the word Islām shares the same root as “silm” and “salām”, the Arabic terms for peace; one of the attributes of God is the “Source of Peace” (As-Salām); the Qur’ān refers to Paradise as the “Abode of Peace” (Darussalām). Peace is further the greeting of Islam (assalāmu alaykum), the language of the righteous, and Muslims continuously reiterate their wish for peace in their daily prayers. Furthermore, the Qur’ān associates peace with food, considering it therefore not only as a human right but as a basic need.

The Islamic tradition considers conflict a human phenomenon. In his work The Unrestricted Thunderbolts, Muslim scholar Ibn Qayyim al-Jawziyya (1292-1350) observed that “conflict occurs necessarily and unavoidably between people due to the disparity in their wills, understandings, and sharpness of mind. What is disliked is aggression and hostility to each other. Otherwise […] conflict does not hurt; it is unavoidable since it is constitutive of the human creation.” According to Ibn al-Qayyim, “conflict is defined as the situation where the origins are incompatible, the ways are divergent or the goals are contradictory.”

Moreover, conflict is not considered to be an inherent attribute of the parties. Instead, it is seen as a relationship between parties that has been altered and needs to be restored. Correspondingly, the Islamic Arabic expression for mediation is “bond mending” (islāhu thātil bayn). It is therefore envisaged that such a breakdown in a relationship may occur between people who are not necessarily “bad”.

Preventing violence, transforming conflict and promoting peace is not exclusively the task of the state in Islam. Instead, it is the duty of each and every Muslim: “Making peace justly between two parties is an act of charity” (Prophet Muhammad). “What is more valuable than fasting, praying, and almsgiving is to restore the bonds between conflicting parties” (Prophet Muhammad).

When mediation becomes difficult, as in the case of asymmetric conflicts where a more powerful party refuses to talk to a powerless one, it is the duty of the whole Muslim community to engage in a “good intervention” to bring the more powerful actor to the dialogue table: “If two groups of believers come to fight one another, then amend the relation between them. But if one of them oppresses the other, fight the oppressor until it submits to the command of God. If it complies, then amend the relation between them with fairness and be just. God loves those who are just.” (Qur’ān, 49:9) This verse sets out the successive steps of a process: 1) Try to mediate between the two fighting groups; 2) If one group refuses mediation, rejects conflict settlement and persists in oppressing the other group, the Islamic community has the duty to intervene until the oppressor reconsiders his position; 3) If the oppressor abandons oppression and embraces peace, resume the mediation with fairness and do not be unjust with the group who ceased oppression.

If the community fails to engage in a good intervention, the powerless actor has the right to resist in order to re-establish the power balance. Muslims, however, are ordered to resist in a “good way” in line with Ihsān, the highest attribute of Islamic faith. This is a difficult Islamic concept to translate, but may be considered as the sum of virtues since it covers (1) the good, (2) the fair, (3) the true, (4) the right and (5) the beautiful. “Resist with Ihsān, then verily he, of whom you are an enemy, will become as though he was a close friend.” (Qur’ān, 41:34) This is about the transformative power of non-violence.

Dealing with conflict in the Islamic tradition must also be governed by the five Islamic imperatives of Ihsān, ‘Adl (fairness) that must guide conduct even towards adversaries (“O you who believe, be upright for God, bearers of witness with justice, and let not the enmity and hatred of anyone incite you not to be fair; be fair, that is closer to piety.” [Qur’ān, 5:8]), Karāma (human dignity) conferred on all the children of Adam, Wasatiya, the avoidance of the extremes, and, above all, the overarching requirement of Rahma (true love), as the Muslim is advised to start all his/her daily actions, be it religious duties or worldly affairs, by saying “Bismillāh Ar-Rahmān, Ar-Rahīm” (In the name of God, the Loving, the Love-Giving).

It is unfortunate to observe the gap between the Islamic normative framework of peace promotion and the reality of Muslim societies today, torn apart by so many violent conflicts. Much effort is needed in terms of research, capacity building and dissemination, in order to promote the culture of non-violence and provide young peace actors across the Islamic world with both traditional and modern tools. This will hopefully enable conflicts to be transformed by peaceful means.

About the Author

Dr. Abbas Aroua, a medical physicist by training and adjunct professor at the Lausanne Faculty of Medicine, is the founder and Director of the Cordoba Foundation of Geneva which aims to promote peace and dialogue between cultures and civilisations and which is active across the Arab world and the Sahel. He is engaged in various non-profit activities, and has written articles and books on conflict transformation and human development. From 2010 to 2013, he taught at the Basel World Peace Academy, Switzerland. He also heads the “Arab world” department of the transcend.org network and is the author of The Quest for Peace in the Islamic Tradition.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit our CSS Security Watch Series or browse our Publications.