This article was originally published by the Foreign Policy Research Institute (FPRI) on 1 September 2017.

Though seldom mentioned in the same breath as prolific Western jihadi producers such as France, Germany, and Belgium, Canada has a long and often overlooked history of producing jihadists. From the “Millennium Bomber” and the “Toronto 18” to the “Ottawa 3” and the “Calgary cluster,” jihadis have organized on Canadian soil to carry out attacks, both in-country and around the world. While Canadians have fought on jihadi battlefields as far flung as Afghanistan and Syria, their government has failed to implement comprehensive counterterrorism and deradicalization measures. Lagging far behind its Western allies, Canada implemented its first counterterrorism strategy in 2012 and has yet to create a desperately needed nationwide deradicalization program. The rise of ISIS and lone wolf attacks has increased the need for these reforms.

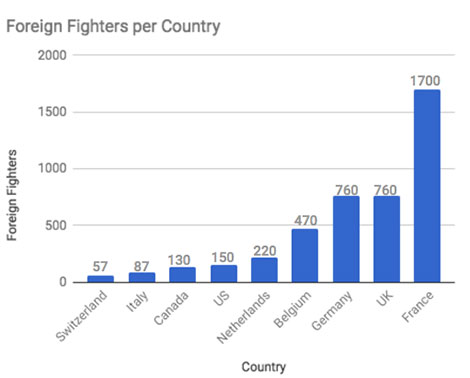

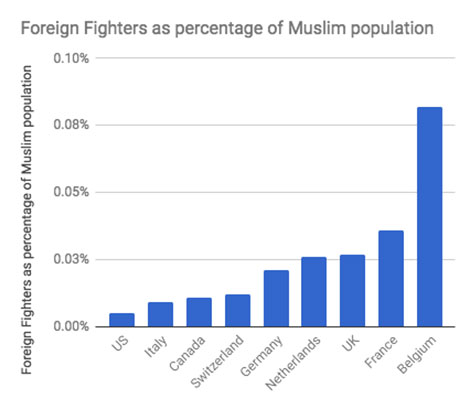

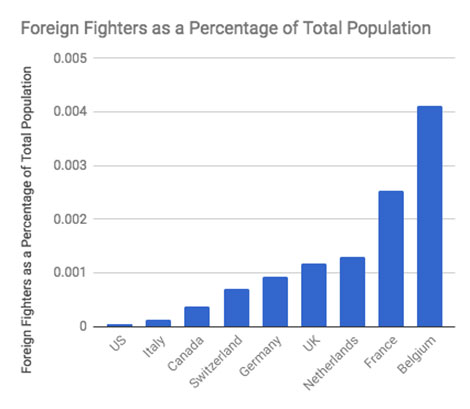

Though the United States has a Muslim population over triple the size of that of its northern neighbor, the two countries have seen an approximately equal number of their citizens join the Islamic State (see Graph 1 below). Canada is more similar to Italy and Switzerland—European countries far closer to the Islamic State—in terms of fighters sent in relation to its Muslim/overall population than to the equidistant United States (see Graphs 2 and 3 below). The defeat of the territorially based Islamic State will surely herald an influx of Canadian jihadists to their home country. However, the provisions introduced in the Combating Terrorism Act of 2012 and strengthened in the Anti-Terrorism Act of 2015, which prescribe lengthy prison sentences for any citizen “knowingly participating in or contributing to any activity of a terrorist group for the purpose of enhancing the ability of any terrorist group to commit a terrorist activity,” will do a great deal to mitigate the risks from this group. The greater threat to Canada lies in the radicals who never travelled to the Islamic State, thereby making themselves known to Canadian intelligence services, but instead remain embedded amongst the Canadian population. While there are a number of potential policies that Canada could implement to help combat homegrown jihadism, this analysis posits that a more comprehensive and reformed implementation of the Canadian Multiculturalism Act (CMA) and the creation of a national deradicalization program offer the two most pragmatic solutions to mitigate the threat posed by Canadian jihadis to Canada.

Graph 1

Graph 2

Graph 3[1]

Case Studies

Although Canada has produced hundreds of jihadis since the 1980s, this analysis will focus on six specific individuals/groups that epitomize the evolution of the jihadi movement in Canada over the last two decades and the Canadian legislation that failed to adapt to this evolution.

Ahmed Said Khadr: The Dawn of the Canadian Jihadi Movement

While thousands of “Arab Afghan” foreign fighters waged jihad against the invading Soviets during the Soviet-Afghan War, two Canadians, Egyptian-Canadian Ahmed Said Khadr and Algerian-Canadian Fateh Kamal, came to fill prominent roles in the fledgling mujahideen and the jihadi movement that emerged as its derivative long after the Soviets withdrew. Though not a fighter himself, Khadr played a crucial role in funneling desperately needed funds—some of which were provided by the taxpayers of Canada through the Canadian International Development Organization—to the mujahideen through his Pakistan-based charity networks beginning in 1985.[2] A close friend to Osama bin Laden, Khadr and his family became thoroughly enmeshed in the web of global jihad. After Canadian Prime Minister Jean Chretien personally intervened in 1995 to have Khadr released from prison in Pakistan—a sentence he was serving on the charge that he plotted to bomb the Egyptian embassy in Islamabad—Khadr and his sons continued to work with bin Laden and other “Arab Afghans” who had stayed in country after the Soviet-Afghan War ended in 1989.[3] Though the man known as “al-Kanadi” would be killed in a gun battle with the Pakistani military in 2004, his son Omar continued his father’s jihadi legacy, eventually being detained in Guantanamo for killing an American serviceman in 2005 before being released on bail in 2015. While the Soviet-Afghan War ended in 1989, many of the “Arab Afghans” would travel to wage jihad in Bosnia three years later.

Fateh Kamel: An Example of Canadian Negligence

Although Fateh Kamel fought the Soviets in Afghanistan, he only rose to prominence later as a leader of the jihad in Bosnia beginning in 1995. In the last years of the Soviet-Afghan War, Kamel moved to Canada, where despite being a veteran jihadi he was able to obtain citizenship after marrying a teacher. A member of the al-Qaeda aligned Armed Islamic Group (GIA)—a group to which Ahmed Ressam was also a member—Kamel became known as a dashing and efficient operator. After organizing charity work in Canada aimed at filling the coffers of the GIA in Bosnia, Kamel travelled to Europe himself.

Despite coming to the attention of the Italian authorities for his fiery recruitment speeches in support of the Bosnian jihad at Anwar Shaaban’s Islamic Cultural Institute in Milan, Kamel was able to travel to Bosnia, where he served as the third in command of Shaaban’s El-Mudzahedin unit. During this time, Kamel was also responsible for coordinating a series of brazen bombing attacks on Paris’ metro stations in 1995 with the GIA, which had gained such a reputation for ruthlessness that even al-Qaeda attempted to disassociate itself from the group.[4] In 1999, Kamel was arrested in Jordan and extradited to France, where he was sentenced to eight years in prison. After serving six years of his sentence, Kamel was released on good behavior whereupon he moved to Canada. Though he has repeatedly applied for a passport, Kamel has not been allowed to leave Canada since returning as the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS) still considers him a threat. Kamel’s experiences as a foreign fighter reflect the changing realities of an increasingly potent jihadi movement.

Ahmed Ressam: Canada Wakes Up

An Algerian by birth, Ahmed “the Millennium Bomber” Ressam radicalized long before moving to Canada and applying for political asylum there in 1994. Despite the fact that the French had informed CSIS of Ressam’s radicalism, he was never apprehended and eventually traveled from Canada to Afghanistan to join al-Qaeda in 1998. After receiving extensive training, Ressam was sent to carry out an attack in the United States on bin Laden’s orders. Ressam was specifically chosen because of his previous residency in Canada. Though Ressam was apprehended before carrying out his planned attack in the United States by Canadian border authorities in 1999, he was able to create explosive devices, meet with fellow jihadis, and plan attacks on America all while being wanted for terrorism-related charges by CSIS. He is representative of the honeymoon period before 9/11 where Canada, like most other countries in the West, did not take the threat posed by jihadis seriously. Ressam’s plot, along with 9/11, showed the Canadian legislature and public the need for expanded counterterrorism measures.

The Toronto 18: Bringing the Jihadi Threat Home

The 2006 Ontario attack, an attack which never came to fruition, would have been the largest in North America since 9/11. Planned by a group of jihadis commonly referred to as the “Toronto 18,” the attack targeted numerous high profile targets such as the Canadian Parliament, the headquarters of CSIS, and Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper. Canadian police, in coordination with the country’s intelligence services, penetrated the Toronto 18 and successfully arrested all members. While this operation represented a tremendous success for Canadian counterterrorism agencies, it also reflected a total failure with regard to radicalization prevention and deradicalization on the part of these same authorities.

While the individuals who composed the Toronto 18 had disparate backgrounds, they were all homegrown jihadis in the sense that each was either born in or had lived in Canada for a protracted period of time. Yet, they planned to attack targets that were both embodiments of their native or adopted home country and would have resulted in mass casualties amongst their fellow Canadians. Although Canadians knew that the United States was the chief target for many jihadis, the domestic focus of the Toronto 18’s plot sparked fear of homegrown terrorism with “real consequences for Canadians” in a way that the Millennium Bomber plot never could.[5] While the Toronto 18 formed as a result of pre-existing social networks among its members, the discovery of the group’s 2006 Ontario plot coincides with the beginning of a broader trend in jihadi movements throughout the West away from larger centralized groupings of jihadis and towards more “devolved” formations centered around small groups or individuals.[6] These devolved jihadi formations were far harder for CSIS to monitor, which would come to be especially important with the advent of the Islamic State.

The Calgary Cluster: Exposing CSIS’ Deficiencies

Though Canada enacted its first comprehensive counterterrorism legislation in 2012—legislation which gave CSIS the power to seize the passports of prospective jihadis and detain them for up to three days—it did little to prevent scores of Canadian jihadis from leaving to fight elsewhere. Of the roughly 130 Canadians who left their homeland to wage jihad in Syria, six were members of the “Calgary cluster.” This group reflects both the diversity of the Canadian jihadi movement and the failure of Canada’s counterterrorism policy. Three of the members were Canadian converts, while the other three were from Canada’s Somali, Palestinian, and Pakistani communities.

Though the men did not travel to Syria together, they often worshipped collectively at Calgary’s 8th and 8th Mosque and lived in the same apartment building. After member Damian Clairmont departed for Syria in 2012, many of the other members came under suspicion by Canadian intelligence of planning future trips to Syria; some were even put on the Canadian no-fly list. Despite the suspicions of Canadian law enforcement, however, not a single member of the Calgary jihadi cluster was apprehended before leaving Canada to wage jihad. While many of the jihadis used fake papers, the fact that all were able to travel abroad after being labelled jihadists (with the exception of Clairmont who was unknown to intelligence services at the time of his departure) illustrates how inept CSIS was in handling this case. None of the cluster members have returned to Canada, and five are confirmed to have been killed in action.

Martin Couture-Rouleau: The Rise of Lone Wolf Attacks

As a self-radicalized lone wolf, Martin Couture-Rouleau epitomizes the Canadian jihadist that Canada (and the West as a whole) should fear most. A convert to Islam, Couture-Rouleau gained notoriety after killing a Canadian soldier and wounding another in what has come to be known as the 2014 Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu ramming attack. Before the attack, Couture-Rouleau had been known to CSIS; its agents even confiscated his passport in order to prevent him from leaving Canada to join ISIS. The attack Couture-Rouleau carried out is representative of the larger devolution of jihadism in Canada.

A regular mosque attendant, Couture-Rouleau was not associated with a jihadi cluster. Even though he was inspired by ISIS, Couture-Rouleau was not a member of that group and had not travelled to the Islamic State. Furthermore, the attack itself involved Couture-Rouleau using his car to ram two Canadian soldiers, which demonstrates the logistical simplicity of the lone wolf. Couture-Rouleau, a Euro-Canadian convert to Islam, is not reflective of the failings of Canada’s implementation of the CMA. However, he does illustrate the larger deficiencies of Canada’s counterterrorism and deradicalization policies.

As of 2012, Canada had become aware of and taken steps to prevent its citizens from traveling abroad to wage jihad, yet it failed to understand the danger posed by these aspiring foreign fighters to its domestic security. While CSIS considered Couture-Rouleau so committed to waging jihad that they confiscated his passport, the lack of any accompanying measures allowed him to commit an act of terrorism inside Canada. Attendance at a deradicalization program would have been an invaluable accompanying measure to taking the passport of the young Salafi convert—a group which makes up a disproportionate number of Canadian jihadis relative to their proportion of the Canadian Muslim population—yet none were available in his hometown of Saint-Jean-Sur-Richelieu.[7]

The Anti-Terrorism Act of 2015, partially catalyzed by Couture-Rouleau’s attack, strengthened Canada’s legislation on counter terrorism. The law notably enhanced CSIS’ power to make preventive arrests in cases where jihadis are suspected of planning to leave the country by changing the “tripwire” for preventative arrests from will carry out an attack to may carry out an attack. It also expanded the number of days a suspected jihadi can be detained from three to seven.

Policy Recommendations

Canada is held up by many scholars as an outstanding example of multiculturalism and selective immigration, which is to a great extent accurate. Despite this image, Canadian attitudes are not tolerant towards Muslims: in 2016, only 43 percent of Canadians have a net positive opinion of Muslims in contrast to 61 percent who have a net positive opinion of immigrants; and Muslims perceive discrimination at a higher rate than any other group in Canada, with 51 percent stating that they are discriminated against often and 36 percent saying that they are discriminated against occasionally in 2017. The spread of intolerance in Canada partially reflects the country’s failure to effectively implement the CMA.

There has been a serious performance gap between the tenets laid out in the CMA and its actual implementation. While the CMA should “encourage and promote exchanges and cooperation among the diverse communities of Canada” as the legislation states, the reality is that implementation of the CMA and this tenet in particular often falls short of its stated objectives. This deficiency has enabled the spread of “groupism,” whereby Canadian immigrants have gravitated to and formed communities centered around shared ethnicity and cultural traditions.[8] Groupism can contribute to “us vs them” dichotomies and lead to feelings of resentment and alienation amongst members of immigrant communities. This, in turn, can hinder the efforts of Canadian intelligence and law enforcement to gain the trust of these communities. Some immigrant groups have been more affected than others.[9] Many Somali-Canadians, for example, live in communities so segregated and impoverished that prominent Canadian counterterrorism scholar Lorne Dawson describes them as “Ghettoized.”[10] As a result, though Somalis represent a miniscule five percent of Canada’s Muslim population, they have produced a disproportionate number of Canada’s jihadis.

While feelings of alienation and isolation have catalyzed the growth of jihadism among immigrant communities, positive interactions between radicals and non-radicals have proven to be crucial in preventing radicals from perpetrating violence. This relationship is illustrated in an interview conducted by Gaetano Ilardi with a former Canadian jihadi and Pakistani immigrant, who stated that moving to Canada made him “re-consider his extreme beliefs as a result of his daily contact with regular Canadians.”[11] Thus, positive interactions between Canadians from different backgrounds as advocated by the CMA offer an avenue towards preventing acts of jihadi violence against Canada. Interactions that foster cross-cultural exchange should, however, go beyond tokenistic “multicultural education that focuses only on the superficial celebration of culture through festivals, cultural days, and ethnic costumes.”[12] Rather, they should be centered around the positive day-to-day interactions promoted by diverse schools, neighborhoods, and workplaces. While Canada is far better than most Western countries in creating these spaces, it is by no means perfect. Non-white Canadians are twice as likely as their white counterparts to “experience low-income rates.” Although socio-economics is not the primary motivator for radicalization in the vast majority of cases, it can contribute to isolating minorities and keeping them from interacting with Canadians of other backgrounds, allowing feelings of alienation and embitterment against Canadian society as a whole to take root.[13]

There are a variety of ways that Canada can go about better implementing the CMA. Firstly, recent immigrants, especially those who have not come to Canada as a result of selective immigration policies, should be given greater levels of post-immigration support. This support could entail a variety of initiatives ranging from increased language courses for those not already proficient in English or French to assistance in finding permanent—rather than simply temporary as it currently does—housing and job placement, which could help decrease the problem of underemployment that costs immigrants “over 4 billion in lost earnings annually.” Secondly, Canada’s government should take steps to “de-mystify” Islam for its populace. This initiative could utilize a wide variety of platforms such as the education system and social media to address common misperceptions of Islam, which could partially alleviate the sense among the majority of Canadian Muslims that discrimination against them is on the rise.[14] It would be beneficial to both Muslims and non-Muslims alike because many Canadian former-radicals have stated that their lack of basic knowledge of Islam contributed to their radicalization.[15] Together, post-immigration support and a program to demystify Islam as a whole offer two of the most workable reforms to the implementation of the CMA.

A national program that deals with deradicalization and radicalization prevention would complement a reform of the implementation of Canada’s multiculturalism policy and mitigate the threat posed by Canadian jihadis to Canada. Contrary to what some scholars argue, radicalization in Canada is conducted entirely online in very few cases.[16] Rather, as evidenced by studies conducted by Sam Mullins and Gaetano Ilardi, social interaction is still instrumental in the radicalization of Canadians. Radicals can still be identified by family, friends, and faith leaders, instead of exclusively by intelligence services as is the case with many of those who radicalize entirely online. Under Canada’s current counterterrorism policy, however, there is an intervention gap as very little can be done for identified radicals aside from preemptive detention by law enforcement in the most serious instances. Calgary’s ReDirect deradicalization and radicalization prevention program offers a template that could be reproduced on a national scale. ReDirect has been described as “an education, awareness and prevention program aimed at stopping the radicalization of young people toward violent extremism.”[17] While ReDirect is in its early stages, the program is already proving successful as a result of its strong partnership between local police, community leaders, and experts on radicalization. It allows those close to radicals and potential radicals a support system mandated to intervene independently of more heavy-handed intelligence organizations like CSIS. ReDirect epitomizes how partnering with the local Muslim community is imperative for any successful deradicalization effort in order to dispel the clash of civilizations narrative favored by radicals.

There are, however, limits to the effectiveness of community policing. ReDirect’s success is in part due to the Calgary Police Service’s overwhelming favorability with city residents.[18] This stands in stark contrast to the other two deradicalization programs that currently exist in Canada—Toronto’s Focus Rexdale and Montreal’s Center for the Prevention of Radicalization Leading to Violence—which have both been hindered by unpopular police departments, local bureaucracies, and distrust from community members.[19] A national agency dedicated to deradicalization and radicalization prevention would complement local programs and become more involved in areas where community policing proves ineffective.

The expansion of programs to cover towns and midsize cities would be particularly useful given the increasing dispersion of jihadi recruitment to locales other than Canada’s major cities. This expansion would be facilitated by revamping Canada’s Integrated National Security Enforcement Teams (INSET), which are currently mandated to promote Canadian national security through interagency cooperation and information sharing amongst Canada’s various national, provincial, and municipal agencies such as CSIS, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, Canada Border Services Agency, and the police. In addition to expanding this program to cover areas beyond Canada’s major cities, INSET offers an existing platform which could be coopted to coordinate between a new national deradicalization agency and INSET’s current participating agencies. The creation of a Canadian national deradicalization program that integrates existing infrastructure like INSET and community policing models like ReDirect is crucial to stymying radicalization and securing Canadian national security.

Securing Canada Will Help to Secure America and the World

While the Anti-Terrorism Act of 2015 and the decline of ISIS have resulted in a significant decrease in Canadian radicals travelling to the Islamic State to wage jihad, these two factors have also sequestered jihadis on Canadian soil with few accompanying measures to keep them from committing attacks in their homeland. In addition to its own domestic stability, Canada’s dearth of policy on combating jihadism and radicalization poses a threat to American national security. While scholars such as Phil Gurski argue that the threat posed by Canadian jihadists to the United States is often exaggerated, they concede that this threat remains plausible.[20] Utilizing the expansive and porous Canadian-American border, Canadian jihadists have attempted and carried out attacks on American soil.[21] In addition to Ahmed Ressam—who was apprehended before he could carry out his attack—Amor Ftouhi stabbed an American police officer in a deliberate act of jihadi violence in a June 2017 attack at Bishop International Airport, illustrating how Canadian jihadis continue to pose a tangible threat to the American homeland. Ultimately, the measures posited in this analysis offer pragmatic reforms to Canada’s current counterterrorism and deradicalization policies that should be implemented in order to stop the growth of the Canadian jihadi movement and mitigate the danger its poses to Canada, America, and the world.

Notes

[1] For Graphs 1, 2 & 3, for numbers on state population and Muslim populations per state as of 2016, see: CIA World Factbook, accessed June 20, 2017, https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/; for numbers of foreign fighters per state as of December 2015, see: “Foreign Fighters,” The Soufan Group, last modified December 2015, accessed May 27, 2017, http://soufangroup.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/TSG_ForeignFightersUpdate3.pdf.

[2] Barry Cooper, “Exposing Canada’s complicity in the export of terrorism,” Calgary Herald, April 28, 2004.

[3] “Khadr’s Father met Osama bin Laden in Pakistan during Soviet War,” National Post Canada, July 16, 2008.

[4] Cooper, “Exposing Canada’s complicity in the export of terrorism,” Calgary Herald, April 28, 2004.

[5] Lorne Dawson, “Trying to Make Sense of Homegrown Radicalization: The Case of Toronto 18,” in Religious Radicalization in Canada and Beyond, eds, Paul Bramadat and Lorne Dawson (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2014), 64.

[6] Michael G. Zekulin, Canada’s New Challenges Facing Terrorism at Home (Calgary: Canadian Defense and Foreign Affairs Institute, 2014), accessed June 20, 2017, https://d3n8a8pro7vhmx.cloudfront.net/cdfai/pages/442/attachments/original/1418341197/Canadas_New_Challenges_Facing_Terrorism_at_Home.pdf?1418341197.

[7] Gaetano Joe Ilardi, “Interviews with Canadian Radicals,” Studies in Conflict and Terrorism 36 (2013), 716.

[8] Michael Zekulin, “Terrorism in Canada,” Journal of Military and Strategic Studies 13, no. 3 (2011), accessed June 20, 2017, https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Daniel_Kollek/publication/8628348_Terrorism_in_Canada/links/54b819360cf2c27adc48a9e5.pdf. .

[9] Phil Gurski, The Threat From Within (Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 2016), 111-112.

[10] Dawson, “Trying to Make Sense of Homegrown Radicalization,” 70.

[11] Ilardi, “Interviews with Canadian Radicals,” 721.

[12] Miriam Chiasson, “A clarification of terms: Canadian multiculturalism and Quebec interculturalism,” [Report prepared for David Howes and the Centaur Jurisprudence Project, Centre for Human Rights and Legal Pluralism] McGill University, 2012, Accessed July 17, 2017, http://canadianicon.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/TMODPart1-Clarification.pdf.

[13] Sam Mullins, “Global Jihad: The Canadian Experience,” Terrorism and Political Violence 25, no. 5 (2013): 31-32, accessed June 19, 2017, http://ro.uow.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2056&context=lhapapers; Also, see Ilardi, Interviews with Canadian Radicals,” 720.

[14] Uzma Jamil, “Trying to Make Sense of Homegrown Radicalization: The Case of Toronto 18,” in Religious Radicalization in Canada and Beyond, eds. Paul Bramadat and Lorne Dawson (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2014), 148.

[15] Ilardi, “Interviews with Canadian Radicals,” 724-725.

[16] Mullins, “Global Jihad: The Canadian Experience,” 20.

[17] Peter Ottis, “The Promises and Limitations of Using Municipal Community Policing Programs to Counter Violent Extremism: Calgary’s Re-Direct as a Case Study,” Master’s Thesis, Norwegian University of Life Sciences, December 2016, 36, Accessed June 20, 2017, https://brage.bibsys.no/xmlui/bitstream/handle/11250/2443196/The_Promises_and_Limitations_of_Using_Municipal_Community_Policing_Programs_to_Counter_Violent_Extremism.pdf?sequence=1.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Gurski, The Threat From Within, 123-124.

[21] Canadian jihadis who have attacked or attempted to commit attacks on American soil include Ahmed Ressam and Amor Ftouhi. For information on Ressam see: “Ahmed Ressam’s Millennium Plot,” PBS Frontline, last modified 2014, accessed June 26, 2017, http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/trail/inside/cron.html. For information on Ftouhi see: Jeff Karoub and Mike Householder, “Canadian Charged in US Airport Attack Investigated as Terror,” military.com, last modified June 21, 2017, accessed July 8, 2017, http://www.military.com/daily-news/2017/06/21/canadian-charged-us-airport-attack-investigated-terror.html.

About the Author

Nate Kennedy an intern at FPRI and a senior at Haverford College.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit our CSS Security Watch Series or browse our Publications.