Mediation Perspectives is a periodic blog entry that’s provided by the CSS’ Mediation Support Team and occasional guest authors. Each entry is designed to highlight the utility of mediation approaches in dealing with violent political conflicts. To keep up to date with the with the Mediation Support Team, you can sign up to their newsletter here.

A pastor tells a negotiation expert: “The truth will set you free!” The negotiation expert responds: “What “truth”? It all depends on your perception! And anyway, why are you telling me this; what is the interest behind your position?” One can imagine how this type of interaction could quickly degenerate into miscommunication. However, one can also take it as a starting point to reflect on how different professional communities – in the following case, religious actors and negotiation and mediation experts – can interact constructively.

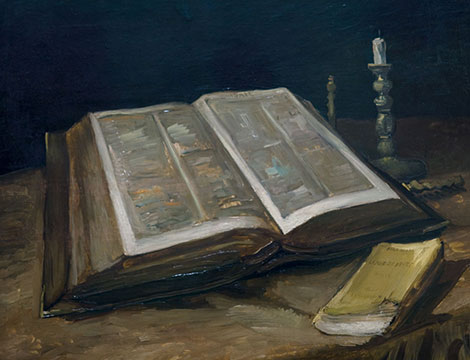

The purpose of today’s blog, which is the first of a multi-part series, is to see what guiding principles can facilitate the above interaction. The blogs that will follow this one will then illustrate how mediation can be performed by different religious communities and profitably rely on religious sources, such as the Bible or the Quran, to train negotiators and mediators.

Why use religious resources?

Indeed, why should mediation or negotiation trainers use religious resources in their interactions with a religious community? One obvious reason is to make the principles behind an attempted reconciliation more legitimate or more easily digestible. The language used, after all, is one that that religious people understand and can grapple with. Additionally, such terminology can make ideas come alive, mobilize a community’s religious resources, and talk directly to the key ideas, values and narratives of the given community.

Dangers when doing this

At the same time, using religious resources is potentially dangerous. By relying on them, one inevitably makes legitimization arguments from outside a community, even if authentic interpretations of religious texts are only possible from within the community in question. The problem is not only cherry picking quotes out of context, or to underline the message one seeks to make, but also who is doing the picking. The more “outsider” one is to a given religious community, the less interpretative authority she or he has. If one nevertheless tries to use a religious text to argue a point, a real or perceived imposition or manipulation of norms may result. That’s not appropriate because imposing a worldview or a way of framing issues – which is at stake when meddling in a community’s religious narrative – is potentially also a form of violence.

Criteria to use Religious Resources

Given the above problems, one needs to be guided by criteria that identifies the “if, when and how” of using religious resources to teach negotiation or mediation skills, and to reach out to communities of faith. The following principles may be helpful, even if they’re not totally comprehensive.

- Insiders can use religious resources for legitimization, but outsiders can’t. The point here is that trainers should use religious resources to legitimize an idea only if they are familiar with the religious traditions at play, and if they are perceived as “insiders” with the religious community they’re dealing with. Thus, a negotiations trainer from a Christian background can use biblical language to legitimize an idea to fellow Christians, but the trainer should also shy away from this approach when talking to other religious groups. Interpretation, in short, is an intra-community activity. Coming from outside a group and claiming some kind of authority or truth that’s based on the interpretation of the group’s religious texts can be seen as imposing your “outsider” views on others, or even applying a form of violence.

- Outsiders can use religious resources only for purposes of accessibility, not for legitimization. If you exist outside a particular religious community, you are much more limited in how you can use a religious text. What outsiders may be able to do, if they actually learn to understand and respect another religious tradition, is to refer to a religious saying, item or metaphor (such as “shura” in Islam to refer to a consultation process) or even to quote from its texts (which can be more delicate) in order to communicate more clearly and accessibly, but NOT for purposes of legitimization. Making an idea digestible means linking it to resources that may or may not be taken up by the receiving community. An outsider to the community can do this because he or she does not claim authority. In contrast, if the outsider seeks to legitimize an idea by referring to a religious text, this person will end up meddling with the community’s internal authority and its own legitimization processes.

- Develop ideas in a two-way form of dialogue. Even as an insider, don’t use religious texts as a one-way tool to “prove” your rightness, but rather as a way of developing ideas and grappling with possible new meanings, interpretations and nuances that may be helpful. By taking a two-way approach, the non-religious principle and the religious text can end up teaching something to the other. Coming from a negotiations standpoint, it is also vital to be humble and stress that the origin of an idea is more likely to be in the religious text (e.g. the Bible) than in the most recently published article on negotiations or mediation. Mahatma Gandhi’s dictum comes to mind: “I have nothing new to teach the world, truth and non-violence are as old as the hills.”

- Use open questions and ask for peer- or elder-review: As an insider focusing on legitimization and accessibility, and an outsider focusing only on accessibility, there is still an additional criterion to keep in mind: As meaning making is a collective process, check with others who exist in the religious context in question in order to see if your use of a specific quotation is OK. Rather than saying this is the only or best way of understanding, it is advisable to pose your desired point or observation as an open question, and thereby focus on different options of understanding, and not just one which is right or wrong. By taking this tack, one enters into a discussion with the “peers” or “elders” of the respective community over whether a religious text is usable in a particular way or not.

In summary, the use of religious resources to teach negotiation and mediation skills depends on if one is an insider to a specific community or an outsider. It is also important to note that you can be from a religious tradition (e.g. Christian), but not from the sub-community of this tradition (Catholic of Protestant), so you may still be considered an outsider by a religious community. Insider and outsider are thus relative terms, not absolute categories. Even as an insider, the community still needs to be engaged in open dialogue, peer-review and a two-way dialogue of enriched understanding and legitimization. As an outsider, it’s important to be careful and humble. All efforts to legitimize ideas should be avoided. Instead, one should simply focus on effective communications and the accessibility of ideas, which can then be accepted or rejected by the religious community that’s being engaged.

About the Authors

Simon Mason is a senior researcher and Head of the Mediation Support Team at the Center for Security Studies (CSS) ETH Zurich.

Jean-Nicolas Bitter is a Senior Adviser on Religion, Politics, and Conflict in the Human Security Division of the Swiss Federal Department of Foreign Affairs. The opinions expressed here are exclusively his own.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit our CSS Security Watch Series or browse our Publications.